Rolling Massage Creams

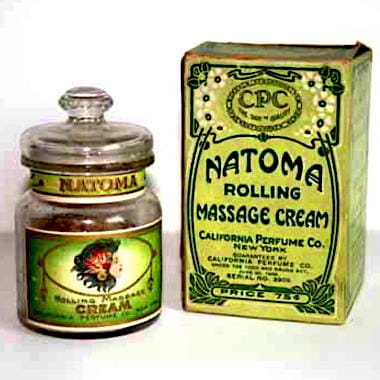

The most popular rolling cream of the twentieth century, Pompeian Massage Cream began its life in a drug store in Cleveland in 1901 as an after-shave massage cream. The term ‘rolling’ refered to the small, oblong particles – containing dirt and surface skin cells picked up by the rolling cream – that formed as the fingers rubbed the cream back and forth across the skin. The creams were oil-in-water emulsions that were pressure sensitive, so, when rubbed, formed characteristic, tacky rolls. Early versions were pasty solids usually made with casein (a milk protein) that worked best when used on clean skin (Harry, 1973).

Casein

Casein is a protein commonly extracted from milk but was also obtainable from plants such as soya beans. The main use for casein was in cheese but it was also used to make a range of industrial products including cosmetics, ointments, paper, paints, glues, textiles, varnishes and early plastics.

One of the reasons casein was used in rolling creams is that it had emulsifying properties. Milk is an oil-in-water emulsion and it is the natural casein in milk that enables the milk fat to be suspended in microscopic droplets. This gives milk its characteristic cloudy, white appearance.

When making cheese, casein is separated from the rest of the milk using rennet. When produced industrially it is extracted from skim milk by first heating the milk and then precipitated it out with a weak acid such as alum or magnesium sulphate. The casein paste produced is then washed, filtered and press dried, after which a preservative is added to protect it from bacterial or fungal attack.

To make a casein type of massage rolling cream it is first necessary to prepare the casein. This may be done by heating skimmed milk to about 135° F. Then add 10% by weight of Epsom salts or other suitable casein precipitant like dilute hydrochloric acid. Let stand for about one hour and add 1% of sodium aluminium sulfate. Heat to 135° F. to complete the precipitation. Then pass through a suitable filter press or strain through a muslin cloth. Wash out well with water until free from whey. Skimmed milk will yield from 2½% to 4% dry casein but in the moist stage the yield is more.

Add about 0.25% dry benzoate of soda to the casein paste to preserve it.

Now transfer to a jacketed mixer.

Mix at 120° F. until homogeneous. Pass though an ointment mill and fill cold.(Thomssen, 1947, p. 522)

Massage rolling creams

Rolling creams were often called ‘massage rolling creams’ as they were massaged or rubbed onto the skin – massaged in, rubbed out – rather than simply applied. They were more popular in the past and, like cold and vanishing creams, could be made up by a local chemists or druggists from one of many recipes circulating in trade journals.

Rolling Cream

Stearic acid 4 oz. Glycerin 4 oz. Water 16 oz. Potassium carbonate 1 dr. Boric acid ½ oz. Casein, soluble 1 oz. Powdered tragacanth 15 gr. China clay 3 oz. Carmine solution q.s. Perfume q.s. This is to be used as a massage cream

(Braithwaite, Peck, & White, 1909, p. 167)

Barbers

A facial massage was a common barbering service in the past. Rolling creams had a degree of drag that made them ideal for use in facial massage. They combined lubrication with a degree of ‘grip’ on the skin which enabled the barber to work the underlying tissue. Given that the skin had been cleansed with the shaving soap the cream would have been able to work efficiently.

As it was massaged in and rolled off, the rolling cream removed residual traces of soap that remained on the face after it was wiped clean with a towel, which may have helped reduce the possibility of skin irritation. As it worked as an exfoliant it may also have helped reduced the possibility of ingrown hairs.

Step-by-Step Procedure For A Rolling Cream Massage

1. Prepare the customer and steam the face with warm towels.

2. Apply the soft rolling cream.

3. Manipulate the face with rhythmic, rotary, stroking, rubbing movements, performed with the tips of the fingers, until most of the cream has been rolled off.

4. Apply a little cold cream, and cleanse the skin with a few lighter manipulations.

5. Remove all the cream with a warm towel, and follow with a mild witch-hazel steam.

6. Apply one or two cool towels and apply a toilet lotion.

7. Dry thoroughly and powder.(Thorpe, 1953, p. 191)

Like cold and vanishing creams, rolling creams were mass produced in the twentieth century, the most widely known being the version produced by the Pompeian Manufacturing Company.

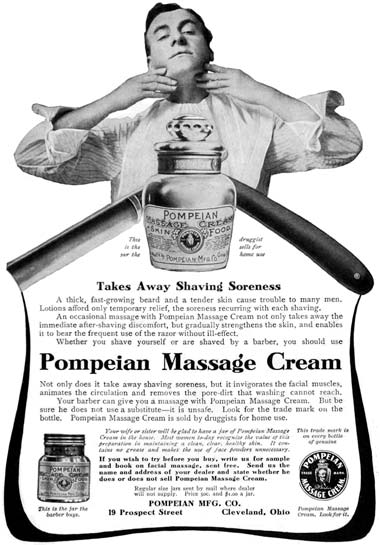

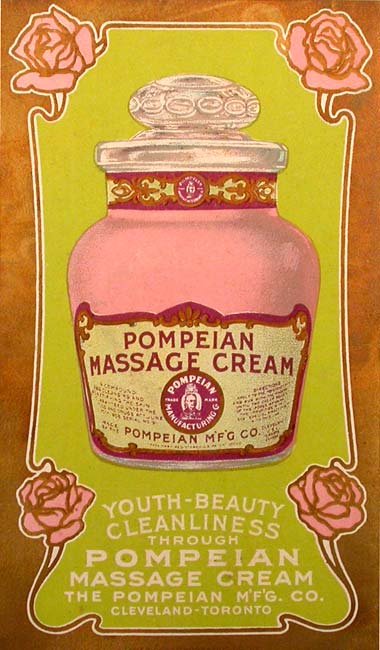

Pompeian Massage Cream

Pompeian Massage Cream was a stiff, casein-based, rolling cream that began life as an after-shave massage cream. As well as casein it also contained benzaldehyde (artificial almond oil) and benzoic acid (a preservative). It was coloured with a pink dye (probably carmine) and advertised to men as a massage cream, a cleanser and a skin food.

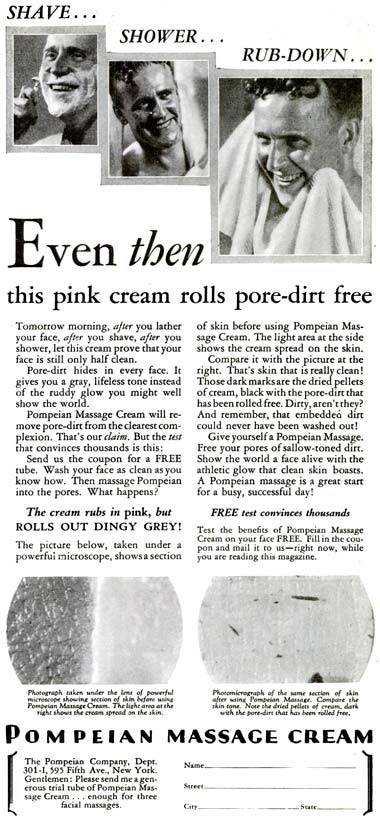

Whether you shave yourself or are shaved by a barber, you should use Pompeian Massage Cream. Not only does it take away shaving soreness, but it invigorates the facial muscles, animates the circulation and removes pore-dirt that washing cannot reach.

(Pompeian Massage Cream advertisement, 1905)

The cream also began to be used by women. When the company realised this they embarked on an extensive advertising campaign directed at them. Sales increased and Pompeian Massage Cream became the best selling face cream in the United States for a time.

When advertised to women, Pompeian highlighted a number of the cream’s features. It was described as a cleanser – when massaged in and rubbed out ‘the dirt comes with it’; as a greaseless cream – it would ‘reduce shine’ without the need for powder which could ‘clog the pores’ or ‘cause blackheads’ while there was ‘no grease to grow hair’ and ‘no stickiness’; and as a skin food – when combined with massage it would ‘reduce wrinkles’, ‘build up sunken cheeks and insure a smooth, ruddy, firm skin’. Some claims were more extravagant, particularly one that suggested it could develop the bust made small ‘by nature, wasted by illness, or reduced by nursing’.

Also see: Pompeian Manufacturing Company

However, not everyone was convinced that massage creams were a suitable face cream for women.

Nearly all skin foods contain lanolin, but massage creams, as such, do not. They are generally made from milk casein, and contain boracic acid and cocoa butter, as a rule these cream have a greater “pull” on the skin surface and are much more suited to body massage, where the epidermis is coarser.

(Poucher, 1926, p. 28)

Other formulations

Given that a rolling cream is based on function rather than its chemical composition, a variety of formulations were possible. Using an ointment or cream base meant that the emulsifying properties of casein were not needed, opening opportunities for other compounds that produce a rolling effect when rubbed on the skin. Starch, methyl cellulose and rubber latex were all used incorporated into petroleum, cold cream or vanishing cream bases.

First make up a mucilage by heating to about 150° F.

Methyl cellulose (high vis.) 5 lbs. Water dist. 95 lbs. Add

Triethanolamine 2 lbs. In another suitable stirring vessel melt together at 160° F.

Stearic acid XXX 5 lbs. Anhydrous lanolin 6 lbs. Mineral oil 12 lbs. Glycerin 10 lbs. Add the waxes to the water solution which has been heated to 170° F. Stir vigorously and continue stirring until temperature reaches 120° F. Then add 6 oz. of suitable perfume and stir until cool.

(Thomssen, 1947, pp. 523-524)

Liquid and lotion forms were also made along with the traditional paste.

Other uses

Rolling creams fell out of favour as face creams in the 1920s but they found cosmetic uses as foot creams and face masks. In both cases their primary function was to exfoliate the skin by massaging the cream in and then rubbing it off. Although you could still find rolling cream face masks in the 1980s their use declined as products that gave better results with less effort arrived on the market.

First Posted: 5th July 2011

Last Update: 13th April 2025

Sources

Braithwaite, J. O., Peck, S. E., & White, E. (Eds.). (1909). Year-Book of Pharmacy. London: J & A Churchill.

Harry, R. G. (1973). Harry’s cosmeticology. (6th ed.). London: Leonard Hill Books.

Poucher, W. A. (1926). Eve’s beauty secrets. London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd.

Poucher, W. A. (1932). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (4th ed., Vols. 1-2). London: Chapman and Hall.

Thomssen, B. S. (1947). Modern cosmetics (3rd ed.). New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

Thorpe, S. C. (1953). Practice and science of standard barbering. NewYork: Milady Publishing Corp.

1905 Pompeian Massage Cream. The bottle is labelled as a massage cream and skin food. Massage does ‘animate circulation’ and was believed at the time to strengthen muscle tissue and even help remove wrinkles and double chins. Being a protein, casein was a known muscle builder and when added to a skin cream was considered to be a skin food.

A jar of bright pink Pompeian Massage Cream.

1911 A. D. S. Rolling Massage Cream.

c.1914 California Perfume Company Natoma Rolling Massage Cream.

1920 A. Simonson Massage (rolling) Cream.

1927 Pompeian Massage Cream. “The cream rubs in pink, but rolls out dingy grey!”.

1935 Baby Touch Company Rolling Cream.