Cake Make-up

In 1936, the Max Factor company was granted the first of two patents for a new make-up base designed specifically for Technicolor film. Initially used in the 1937 film ‘Vogues of 1938’ (Walter Wanger Productions) it was first marketed to the general public as Pan-Cake make-up in 1938.

See also: Pan-Cake Make-up

Pan-Cake went on to become an astonishing success for the Max Factor company. It was widely copied and came to define an entire group of cosmetics, generally referred to as cake make-up. Its dramatic impact was noted in 1952 by Mrs. Veronica Conley, secretary of the Committee on Cosmetics for the American Medical Association (AMA).

Only occasionally do we see revolutionary changes within an industry, whether we are talking about cosmetics or automobiles. Cake make-up, which was first developed to replace greasepaint for theatrical use, has proved a significant advance in the art and science of beautification.

(Veronica Conley as quoted in Wells & Lubowe, 1964, pp. 141-142)

Compressed powders and cake make-up

Although Pan-Cake and other the cake make-ups that followed, were made using a mechanical compressor, these products were very different to the compressed powders that preceded them.

Most compressed powders produced until the end of the 1930s were simply loose face powders compacted into a tablet, held together with a small amount of binder. They were applied to the face with a dry puff and had a similar formulation to the loose face powders that they tried to replace.

See also: Compressed Face Powders

Cake make-up on the other hand can best be described as a powder incorporated into a dehydrated cream (containing oil, a humectant and an emulsifying agent). It required a moist applicator (a wet sponge) to rehydrate the cream and spread it across the skin. As it dried, the make-up formed a thin film of powder-cream that gave the face a smooth, flat finish that masked skin imperfections. Functionally, it was more like a foundation than a face powder and a loose powder was often applied on top of it as a finish.

Precursors

After the success of Pan-Cake, cosmetic chemists examined Max Factor’s patents to find a way to work way around them. In the process some in the industry began to look at earlier formulations and soon realised that Pan-Cake had a some antecedents.

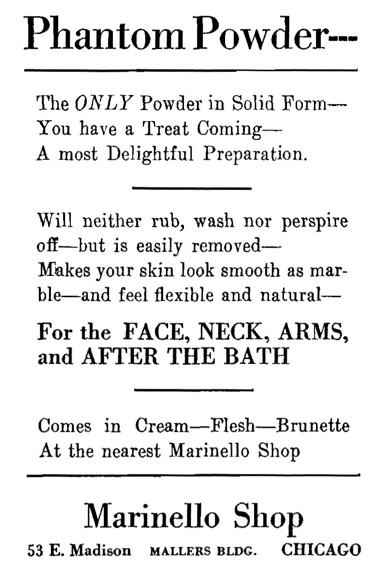

Writing in the Perfumery & Essential Oil Review in 1944, Macias-Sarria described a type of paste make-up sold by a number of cosmetic companies in the early 1910s. It contained lanolin, mineral oil, chalk, glycerine and water made into a paste which was then shaped and hand-pressed into porcelain jars. I have been unable to completely verify the products Macias-Sarria described but I believe one of these was recommended by Ruth Maurer of Marinello, in 1914, when writing under her usual alias of Emily Lloyd. The product she was describing seems to be a type of Phantom Powder her company sold.

A recent innovation in powders though has made a new form very popular, for it seems to combine utility with real cosmetic value.

This powder comes in cake form in small porcelain receptacles, but it lacks the feeling of powder, for to the sense of touch it seems more like a cream.

Absolutely harmless, it has a number of remarkable qualities. When properly applied, it defies detection, does not rub off on the clothing and is not affected by perspiration or cold water, but must be removed by the use of a cleansing cream.

It is applied by rubbing a piece of gauze or a sponge that has first been moistened with a toilet water, over the surface of the cake, and then over the face, neck or hands. The tips of the fingers are then used swiftly over the surface to blend the powder, before dry.

In a few moments the surface is uniformly covered, and yet there is no trace of powder, nor is there any artificial appearance.

For the neck and hands this powder is a positive boon.

Over the inflamed surfaces such as in acne cases it is excellent.

Before going on an outing expedition it cannot be excelled.

However, in using it one must guard against having any trace of oil on the skin before applying it, as otherwise it will positively not adhere, for oil is the one agent that removes it.(Lloyd, 1914, pp. 161-162)

Unfortunately, as Macias-Sarria noted, although the lids on the porcelain containers were sealed with tape they were not airtight, so the cakes soon dried out, came away from the porcelain and were returned. All that was required to fix this was to glue the cakes to the bottom of their containers but no one thought of it.

The make-up paste … was sold in several shades: Flesh, Brunette etc. … In its manufacture the following procedure was employed. The lanolin was melted with the mineral oil and the mixture was incorporated to the powders; finally the glycerin and water solution was added. This gave a mass of the consistency of dough, which was shaped and pressed by hand into porcelain jars with loose porcelain lids sealed with tape. The tape unfortunately permitted moisture to escape and the cake dried out. Jars in that condition were returned to the factory: when shaken you could hear the lose cake flap around inside. If the imagination of someone had worked then, by adding some glue to the bottom of the jars, we would have had a dry cake make-up as early as 1913.

(Macias-Sarria, 1944, pp. 43-44)

The failure of this product did not mean that ‘cake powders’ disappeared altogether. Chilson gives a recipe for one in 1934, well before the arrival of Pan-Cake. It contains all the requisite ingredients: powder (zinc oxide, precipitated chalk and talc), oil (petrolatum), humectant (glycerin) and an emulsifying agent (boric acid) made into a cake. Like Pan-Cake it was also applied with a damp sponge.

[C]ake powders are intended for evening wear and are applied to the skin with a damp sponge. They are made into a heavy dough and are then pressed into flat containers.

Per cent Zinc oxide 24 Precipitated chalk 30 Talc 18 Petrolatum 3 Boro-glycerin mixture 24 Perfume 1 Procedure: Boro-glycerin is made as follows: thirty parts of boric acid are dissolved in seventy parts of glycerin. Add to the boro-glycerin the mixed dry materials and then the petrolatum. Finally add the perfume and mix until smooth.

(Chilson, 1934, p. 310)

All of these early forms exhibited many of the functional advantages of early liquid face powders; they produced a smooth, even finish that was hard to detect and did not easily rub off.

See also: Liquid Face Powders

Formulation

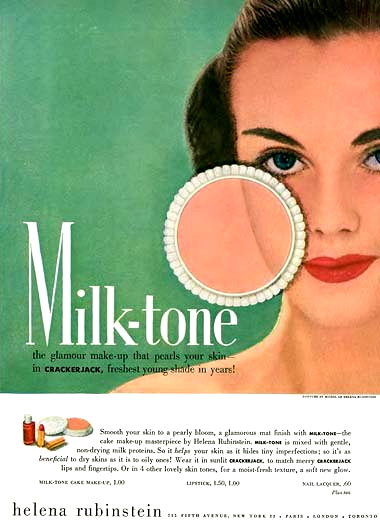

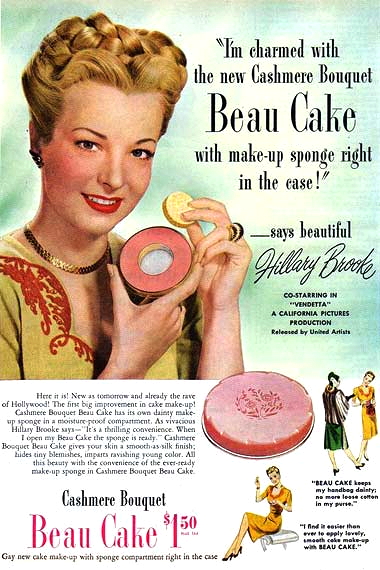

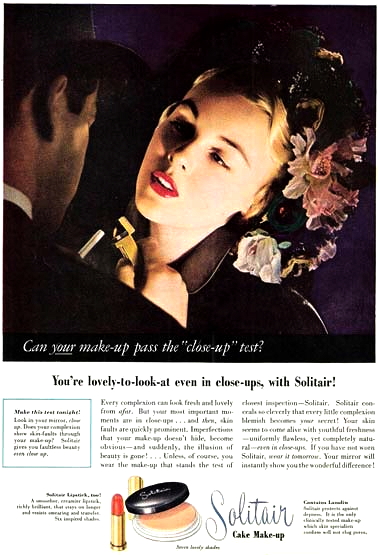

By the late 1940s a number of companies had a cake make-up on the market. Included in the list were Helena Rubinstein’s Milk-Tone, Pond’s Make-up Pat, Tangee’s Cake Make-up, Louis Philippe’s Cake Make-up, Frances Denney’s Over-Tone, Cashmere Bouquet’s Beau Cake, and Campana’s Solitair.

Although there were differences between the various brands, they were all made with powders, oils, humectants and emulsifying agents. The powders used were common to other face powders but the amount of opacifier was increased to enable skin blemishes to be covered by the very thin film; the oil ensured that the make-up was water-repellent; a humectant was put in to stop the make-up from drying out too quickly while it was being applied, i.e., to give it sufficient ‘play time’; while the emulsifying agent kept the oil and water parts of the cream together in a suitable emulsion.

The differences between the various brands of cake make-up were largely due to variations in the ratio of powder, oil and humectant, in the amounts and types of emulsifiers used, and in the inclusion of additional ingredients. For example, one of the commonest complaints made against cake make-up was that it was too drying. To help overcome this, some companies added lanolin into their formulations. Another company, Helena Rubinstein, added milk proteins to reduce skin irritation.

It has been found that if native milk protein is used as a binder the skin which is covered with the make-up film retains its natural moisture. Moreover, emulsifiable make-up cakes in which milk protein is used as a binder instead of soap or soap-like materials will not irritate even extremely sensitive skin and will not cause the formation of pimples or the like.

(Helena Rubinstein, U.S. Patent No. 2,465,340, 1949)

One of the formulas cited in the Rubinstein patent is as follows:

Parts by weight Talc 50 Colloidal kaolin 40 Color pigments 4 Dehydrated skin milk 10 Sodium lauryl sulfate 1 Mineral oil 8 Lanolin 3 Glycerin 10 Methyl p-hydroxy benzoate 0.125 Propyl p-hydroxy benzoate 0.125 Perfume 0.311 Procedure: The talc, kaolin, pigments and sodium lauryl sulfate are mixed together and passed through a pulverizer. The remaining ingredients are then placed in a suitable mixer and the batch is again passed through the pulverizer, after which the mixture is compressed into cakes.

(deNavarre, 1975, p. 948)

Manufacture

Cake make-up was generally made in one of two ways; either by thoroughly mixing the powders (including colours) into a cream, then drying the mixture, pulverising it and pressing it into cakes (the wet method), or by spraying the other ingredients onto the powders as they were mixed, after which they were then pressed into cakes (the dry method). Manufacturing followed processes similar to those used for compressed powders except that during the war, the cakes were often pressed into plastic or glass godets rather than metal which was then in short supply (Hilfer, 1944, p. 286), a practice that continued when hostilities ceased.

Decline

Although cake make-up was initially very successful, and some forms are still made today, it was largely superseded by the pressed cream powders developed after the war. In addition to being less drying, pressed cream powders had the additional advantage of not requiring a moist sponge applicator; they were applied with the fingers or a puff. They also required less skill to produce an even finish, did not need to be followed with powder – some cake make-up also did not need further powdering – and produced a finish that could be touched up very easily during the day.

Updated: 12th April 2016

Sources

Chilson, F. (1934). Modern cosmetics. New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

deNavarre, M. G. (1975). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd ed., Vols IV). Orlando: Continental Press.

Hilfer, H. (1944). Cake make-up. Drug and Cosmetic Industry. 54(3), 285-286.

Hilfer, H. (1948). Facial make-up. Part 1. Cake make-up & face powder. Drug and Cosmetic Industry. 63(2), 170-171, 261, 263.

Hilfer, H. (1948). Facial make-up. Part 2. Cake make-up & face powder. Drug and Cosmetic Industry. 63(3), 316-317, 407-408.

How three color movies are made. (1935). Modern Mechanix & Inventions Magazine. Retrieved January 30, 2014, from http://blog.modernmechanix.com/how-three-color-movies-are-made/

Lloyd, E. (1914). The skin. Its care and treatment (5th. ed.). Chicago: McIntosh Battery and Optical Company.

Macias-Sarria, J. (1944). Process of manufacturing cake make-up. Perfumery & Essential Oil Review. Nov, 43-44; Dec, 47-48.

Wells, F. V. & Lubowe, I. I. (1964). Cosmetics and the skin. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation.

1915 Marinello Phantom Powder in solid form in Cream, Flesh and Brunette shades. It was recommended that it be applied with a sponge soaked in milk.

1941 Max Factor Pan-Cake make-up.

1946 Tangee cake make-up.

1946 Pond’s Make-up Pat.

1947 Frances Denney Over-Tone cake-form make-up.

1947 Helena Rubinstein Milk-tone. This cake make-up uses milk-solids as the binder replacing soap or soap-like ones. According to Rubinstein this resulted in less skin irritation and drying. “Exclusive cake make-up containing beneficial non-drying milk protein. Apply with a moist sponge or cotton. Blend evenly with the fingertips. Covers every tiny flaw with a smooth, protective, more lasting finish. Do not keep wet sponge in container.”

1947 Cashmere Bouquet Beau Cake. The company came up with an innovative way to solve the moist-sponge-in-the-purse problem.

1951 Solitair cake make-up. It came in Natural, Rachel, French Bloom, Brunette, Golden Tan, Bronze and Tropic Brown shades.