Soap and Water

Although all beauty culturists agreed that skin cleansing was the basis for a flawless complexion, views differed about the practicalities of bathing; how best to bathe, when to bathe, whether hot or cold water was best, and on the use soap.

Bathing

Accepted standards of sanitation, general cleanliness and personal hygiene had improved towards the end of the nineteenth century and many people had begun to bath regularly with soap and water, the only practical cleanser available at the time. Given that bathing was a relatively new practice for many of their readers – and for some a health concern – beauty writers of the time provided copious amounts of advice on the subject. Most suggested morning and evening bathing combined with a vigorous rubbing using a sponge, towel or complexion/flesh brush. Hot water was used for some ablutions but cold water was often suggested as well, particularly for rinsing, as it was considered to be ‘invigorating’ and a help in ‘closing’ the skin’s pores.

A perfect condition of the skin can be obtained by frequent bathing only. And frequent bathing means twice every day at least.

Upon rising in the morning the skin is in a moist condition, and covered with poisonous matter thrown off during sleep. A quick sponge bath with cold water, and a vigorous rubbing with coarse towels should not take more than five minutes, and to relieve the skin of this poisonous matter is certainly necessary, otherwise it will be reabsorbed by the system. Again at night, before retiring, the same quick bath should be taken, using hot water instead of cold, relieving the skin of the dust and dirt it has accumulated through the day. Some physicians assert too much bathing is injurious, and many ladies claim they find frequent baths weakening. Remaining in water any length of time, and repeating this process often, undoubtedly is weakening, but quick sponge baths and vigorous rubbing can only be strengthening. The shock of the cold water against the warm skin in the morning sends the blood tingling through the veins, and the exercise of rubbing with flesh brush or coarse towels prevents one taking cold, and is certainly a better tonic for an inactive case than any medicine that could be prescribed by the best physician. The hot water used at night, not only cleanses the skin, but rests the tired nerves and produces sweeter sleep.(Ayer, 1890, pp. 15-16)

When it came to washing the face, cleansing with soap was the preferred option of soap companies, like Pears, Woodbury and Colgate-Palmolive, but many early complexion specialists were cautious about using it. Even beauty experts who were in favour of soap suggested being careful when selecting a suitable brand, not over using it, and making sure that any left-over traces were rinsed away.

Soap is a valuable tonic for the skin, and its moderate use is beneficial. It should, of course, be thoroughly rinsed from the skin; and a dainty French precaution is to use two face-cloths at a time, putting the soapy one aside, so the perfumed water shall remain clear and pure, and rinsing the face with a fresh one. Fastidious care must be given these cloths, and once or twice a week they should be rinsed in an antiseptic solution. The recommendation so often given to rinse in cold water, I consider only less pernicious than to expose the face immediately to air of the same temperature. Instead of the stimulating reaction claimed for it, irritation is often the result.

(Fletcher, 1901, p. 142)

One common annoyance when using soap was hard water. The water supply in many parts of the world contained dissolved minerals which made it difficult to get soap to lather, a situation that continued well into the twentieth century. Two solutions to this problem were to soften the water with a commercial softener or substances like oatmeal, and to substitute rainwater for tapwater.

The trouble about water is that so often in towns we get the wrong type of water. What we need is soft water, which means water free of calcium and magnesium carbonate. Rain water or distilled water can be used instead of hard water, but this is a tiresome business. However, in these days when so many water-softeners are on the market, it is possible for almost every woman to have one.

(Gordon, 1934, pp. 6-7)

No soap

Although many cosmetic companies included soaps in their product range, by the 1920s very few of them were suggesting that soap be used as a facial cleanser. The general preference was to use a cleansing cream or lotion – initially cold cream – instead. In an article published in 1930, in the English version of Harpers Bazaar, only one of the companies listed – Cyclax – recommended using a soap to cleanse the face and even then followed this with a complexion balm.

Eleanor Adair: Ganesh Cleansing Cream.

Elizabeth Arden: Venetian Cleansing Cream; Ardena Skin Tonic.

Harriet Hubbard Ayer: Luxuria Cleansing Cream.

Cyclax: Cyclax Soap; Cyclax Complexion Balm.

Phyllis Earle: Cleansing Cream (Geranium or Lemon).

Innoxa Beauté: Innoxa Complexion Milk.

Myosotis: Antiseptic Cleansing Milk.

Maison de Beauté Pompadour: Eau Folette; Crème Ninon.

Helena Rubinstein: Waterlily Cleansing Cream; Cleansing and Massage Cream.

Suzanne Verdi: Herbal Wash; Cleansing Cream.

The primary reason for the antipathy shown by most cosmetic companies towards using soap and water was economic. There was a lot more money to be made from a client who used a cleansing cream and a skin tonic than there was from someone who cleaned their face with soap and then rinsed with water.

Also see: Skin Tonics, Astringents and Toners

The campaign against soap started by complexion experts in the nineteenth century remained essentially unchanged through the twentieth with the primary arguments being as follows:

Alkalinity: At the end of the nineteenth century soap was produced in a range of forms – tablet, bar, liquid, paste, flaked and powdered – with different soaps being made for specific tasks, e.g., scouring, laundering or bathing. Some of these were alkaline, which could result in the skin becoming rough and tender with long-term exposure, and this situation was exploited by cosmetic companies as a criticism against all soaps.

Dorothy Gray does not advise the use of soap and water for the face, as water does not cleanse the face properly, and soap contains [alkaline] lye and other deleterious ingredients, which in time injure the delicate skin.

(Dorothy Gray brooklet, 1926)

Complexion or toilet soaps made specifically for bathing generally did not suffer from this problem and were widely advertised as being ‘soothing’, ‘velvety’ and, above all else, ‘non-irritating’.

To persons whose skin is delicate or sensitive to changes in the weather, winter or summer, PEARS’ TRANSPARENT SOAP is invaluable as, on account of its emollient, non-irritant character, Redness, Roughness and Chapping are prevented, and a clear appearance and soft velvety condition are maintained, and a good, healthful and attractive complexion ensured. Its agreeable and lasting perfume, beautiful appearance, and soothing properties, commend it as the greatest luxury and most elegant adjunct to the toilet.

(Pears advertisement, 1887)

Drying: Another objection to soap was that it robbed the skin of natural oils which meant it had a drying effect on the skin. Many beauty culturists therefore recommended that a cleansing cream be used instead of, or with soap, and that a skin cream, e.g., a skin food, be applied after washing to replace the oils that had been lost.

Soap for the face? … Not often if Madam values soft clear, colourful skin – not if she would escape premature wrinkles. Medicated soaps are no exception.

But if soap is used occasionally, never fail to use cream afterwards, to restore the natural oil of which soap cleansing robs the skin.(Gordon Gorden Limited booklet, n.d.)

There is some truth to this argument but one that can be easily rectified by applying a suitable emollient after washing. In addition, given that cosmetic companies also recommended applying an emollient after using a cosmetic skin cleanser the argument seems a little spurious.

Soap companies responded to the drying issue with superfatted soaps. These contained unsaponified fats or an excess of fatty acids which remained on the skin after cleansing and acted as an emollient. However, this only worked if the soap was made less effective as a cleanser.

Cleansing power: A third critique was that soap was not able to penetrate the skin as well as a cleansing cream, so it was unable to remove many ‘harmful skin secretions’.

To some skins soap and water—even the best soap and softest water—are fatal. All very sensitive and dry skins seems to be adversely affected, and when there is any acidity or tendency to eczematous affections soap and water are definite irritants; also they do not dissolve the secretions of certain skins, and therefore are not satisfactory as cleansing agents.

(Chrysis, 1928)

The beauty industry was clearly in two minds about the ‘penetrating power’ of soap. Helena Rubinstein, amongst others, sold a reducing soap that was supposedly able to remove excess body fat, so some beauty experts clearly thought soap had extraordinary powers of penetration.

It contains ingredients, guaranteed non-injurious, which rubbed into the skin in the form of a lather, and becoming absorbed by the pores, dissolve and disperse the fatty tissue.

(Helena Rubinstein advertisement for Valase Reducing Soap, 1925)

Opposing views

Cosmetic companies rarely stuck to one objection in their efforts to convince consumers to abandon soap.

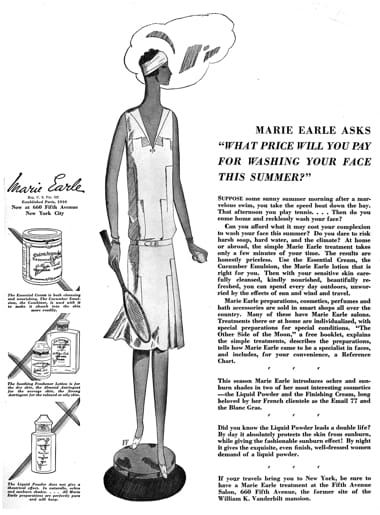

The use of soap and water is not only inefficient (since these agents cannot penetrate sufficiently to do more than cleanse the surface)—but this method is detrimental as well. Alkali is present in the finest of soaps. … The water used is usually hard. … Both are too drying for use on the tender exposed skin of the face and throat.

(Marie Earle booklet, 1933)

Promotors of soap included soap companies, firms like Woodbury who were in the soap as well as the cosmetic business, and some cosmetic companies, such as Cyclax. Medical experts were frequently called in to support their claims.

It is only some exotic beauticians, faddists in the field of cosmetics, who maintain that soap and water are harmful to the skin. Scientists, physiologists, doctors, and especially dermatologists (M.D.’s who have made the skin their speciality) are practically unanimous in declaring that daily cleansing with water and a good soap is essential for the health and beauty of the skin.

(Parker booklet, 1932)

You must use soap and water on your face because it is essential to start the day with a skin that is thoroughly cleansed. … There are women, I know, who have become so use to creaming the face clean that they shudder at the brutal idea of using soap-and-water. Much too harsh, they say. They’re quite wrong. I can honestly say that I have never met a woman whose skin did not quickly improve under my soap-and-water treatment.

(Cyclax booklet, 1935)

See also: Cyclax

Although most cosmetic companies pushed the cosmetic cleanser line they knew that many woman still used soap and water, either in conjunction with, or as an alternative to a cosmetic cleanser. Soaps were often included in a cosmetic company’s product range and many firms were either silent on the use of soap as a facial cleanser or suggested using a cosmetic cleanser in conjunction with soap.

If you feel you must give your skin an occasional soap and water cleansing, always do it before, never after, using the Cleansing Cream. The oil of the cream counteracts the drying effects of the soap and water.

(Barbara Gould booklet, 1931)

Soap companies

Soap companies naturally fought long and hard to keep women using their soaps as a facial cleanser. For much of the twentieth century they mounted extensive advertising campaigns to promote the idea that the daily use of their soap was essential for a good complexion. As with cosmetics, movie stars and other important personalities were used to accentuate the message. Most of their campaigns were positive, but negative advertisements, such as the 1930s ‘Cosmetic Skin’ campaign mounted by Lux soap, were also occasionally used.

See also: Cosmetic Skin

This degree of soap advertising is no longer found today. Traditional soaps went into a decline in the later part of the twentieth century as the use of synthetic detergents became more widespread. First commercially developed in Germany during the First World War – in response to a war-time shortage of fats for making soap – by the 1950s, synthetic detergents were being used as soap replacements in products such as shampoos, body scrubs, syndet bars and foaming facial cleansers.

First Posted: 17th August 2015

Last Update: 14th April 2023

Sources

Ayer, A. G. (Ed). (1890). Facts for ladies. Chicago: Amy G. Ayer.

Barbara Gould. (1931). Any woman can look lovelier [Booklet]. New York: Author.

Chrysis. (1928). To wash or not to wash. Eve: The Lady’s Pictorial. London: Sphere and Tatler.

Cyclax. (1935). Towards beauty: Four informal talks [Booklet]. London: Author.

Daggett & Ramsdell. (1911). Daggett & Ramsdell’s perfect cold cream. Philadelphia, PA: Author.

Dorothy Gray. (1926). The story of Dorothy Gray [Booklet]. New York: Author.

Fletcher, E. A. (1901). The woman beautiful. A practical treatment on the development and preservation of woman’s health and beauty, and the principles of taste in dress. New York: Bretano.

Gordon, J. (1934). Home beauty treatments solving every woman’s beauty problems. London: John Lane, The Bodley Head Ltd.

Gordon Gorden Limited. (n.d.). Princess Pat. For you – exquisite beauty [Booklet]. Ontario: Author.

Joslen, S. (1937). The way to beauty. A complete guide to loveliness. New York: Pitman Publishing Corporation.

Marie Earle. (1933). Understanding your skin [Booklet]. New York: Author.

Parker, J. (1932). The index to loveliness [Booklet]. New York: John H. Woodbury, Inc.

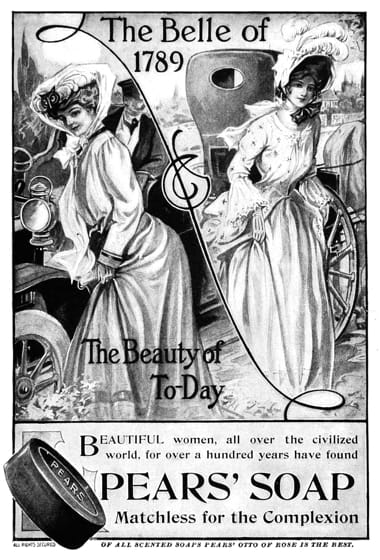

1906 Pears Soap. “Matchless for the Complexion”.

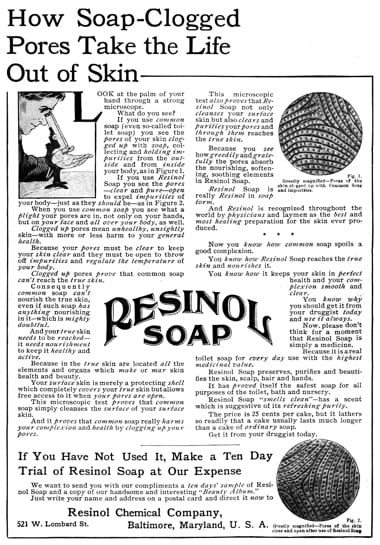

1906 Resinol Soap. Many soap advertisements expressed concern about clogged skin pores, a major concern of beauty experts as well. This one is unusual in that it pushed the idea that some soaps could clog pores.

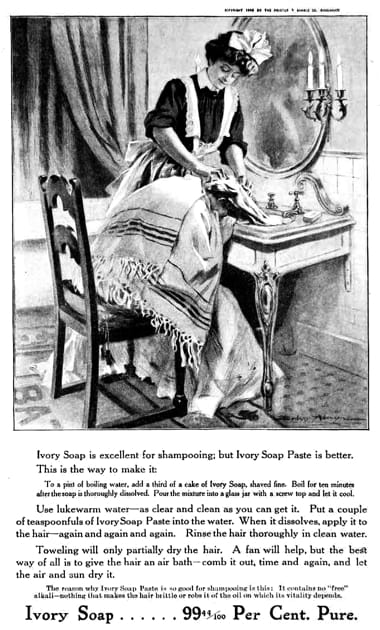

1908 Ivory Paste Soap used before the development of detergent-based shampoos.

1917 Woodbury Soap keeping skin’s pores clean with soap and water.

1925 La-Mar Reducing Soap. There were a number of similar products on the market at this time.

1928 Marie Earle. The company came out strongly against soap in the 1920s.

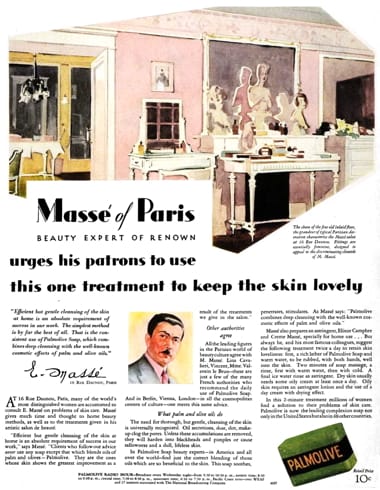

1929 Palmolive Soap. Colgate-Palmolive ran an extensive advertising campaign during this period using endorsements from a range of overseas beauty specialists such as Lina Cavalieri, Dr. Nadia Payot and Emile Massé.

1930 Camay Soap from Procter & Gamble. Eminent dermatologists were frequently said to endorse the use of soap.

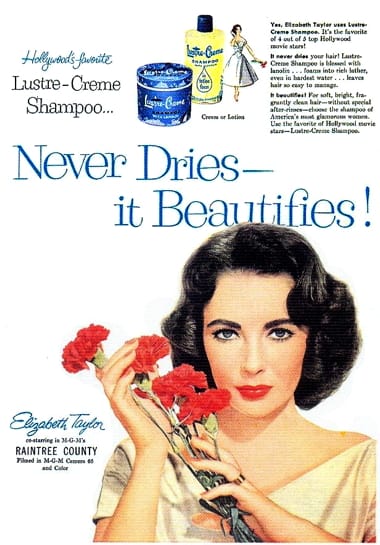

1956 Lux Soap endorsed by Elizabeth Taylor. Developed by Lever Brothers (Unilever) the soap made extensive use of movie stars in its advertising after the Second World War.

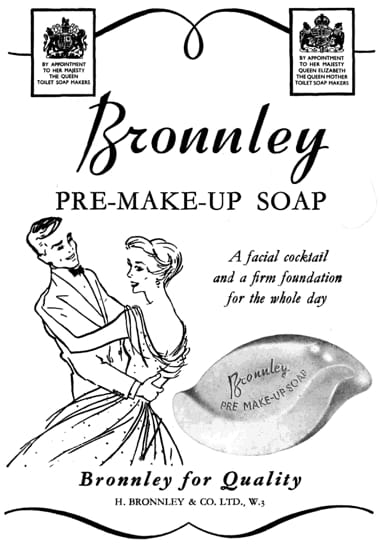

1957 Bronnley Soap aimed at users of the new liquid make-ups developed after the war.

1957 Lustre-Cream Shampoo from Kay Daumit, Inc. One of many shampoos launched after the war; ‘non-drying’ was a common theme.

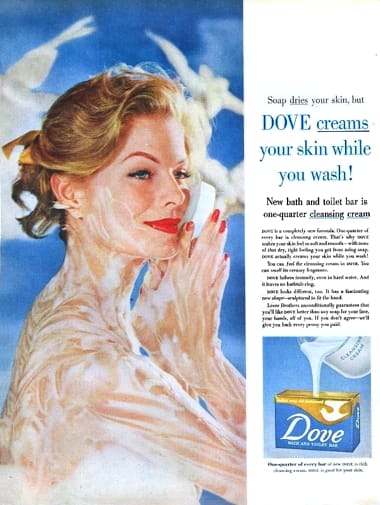

1958 Dove Syndet Bar originally developed in 1953. As well as synthetic detergents, oils and fats, it contained stearic acid which was the basis for the claim that it included a cleansing cream.