Carbonic Gas Sprays

In the 1930s, a number of French beauty salons began introducing carbonic gas sprays – traitements carbo-gazeux – into their facial treatments. The equipment they used – which consisted of a large cylinder of compressed carbon dioxide attached to an atomiser – was originally developed for the medical and dental professions.

After the Second World War the procedure spread to other parts of the world in part due to the introduction of smaller, cheaper hand-held devices. As with the earlier equipment these had also been developed for use by doctors and dentists with patents for them going back to before the war.

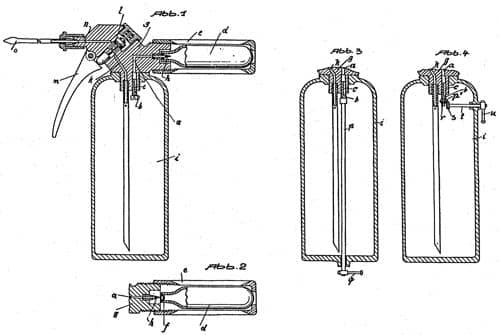

Above: 1930 Drawings from a German patent for an atomiser developed for the medical and dental profession (Patent No. DE514196, 1930).

Uses

Although they are sometimes described as atomisers, there are a number of differences between a carbonic spray powered by compressed carbon dioxide and the one produced by a conventional steamer, atomiser or pump pack. The carbonic gas spray is stronger, is cold – rather than warm or lukewarm – and contains carbonic acid generated when some of the carbon dioxide dissolves in the water.

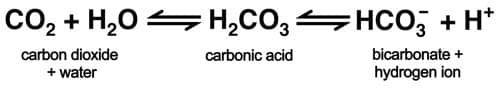

Above: Production of carbonic acid when carbon dioxide dissolves in water.

The device could have also been powered by compressed air or oxygen but carbon dioxide was used because it was believed to have healing effects. This idea goes back to the use of carbon dioxide baths – either natural or artificial – in the treatment of heart disease. One side effect credited to these treatments was improved blood flow to the skin.

The carbon dioxide bath affects the blood-vessels and the heart action, it causes dilation of the peripheral vessels, increasing pulse-pressure, the cardiac output and the blood pressure.

(Kovács, 1949, p. 204)

The beauty results claimed for the carbonic spray are not limited to the effects generated by the force of the spray and the carbonic acid it contains. The device also acts as a conventional atomiser which meant that astringents, herbal ingredients or other substances ccould be added to the water to create supplementary effects. These additions had to be filtered to remove anything that might block the nozzle. The water was distilled to remove any impurities.

See also: Vaporisers (Steamers & Atomisers)

Collectively, the benefits claimed for the carbonic gas spray included the following:

1. The high pressure produced by the spray micro-massaged the skin, cleansed the surface and accelerated desquamation.

2. The cooling effect of the spray toned the skin.

3. The dissolved carbonic acid helped protect the skin against microbes.

Other effects claimed for the treatment depend on the additional substances added to the water.

Devices

In the 1950s and 1960s, a number of companies advertised carbonic gas sprays for use in Beauty Culture. In France these included: Carbo-Douche (Socarb, 14 Rue de Nice, Paris); Atomos (France-Etranger, 10 Rue Louis-Phillippe, Neuilly); and the Carbatom (S.E.R.N.O., 28 Rue de Liège, Paris). These are good examples of the three types of appliances used in these treatments, the main difference between them being the way they were charged.

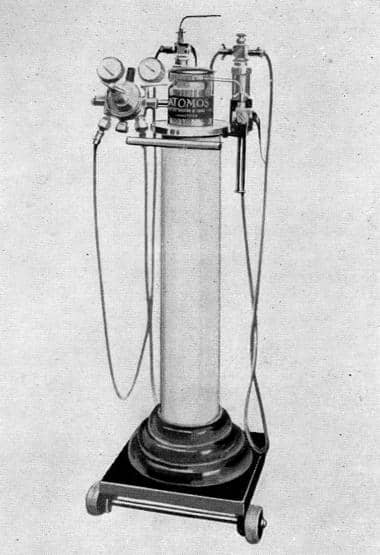

Atomos

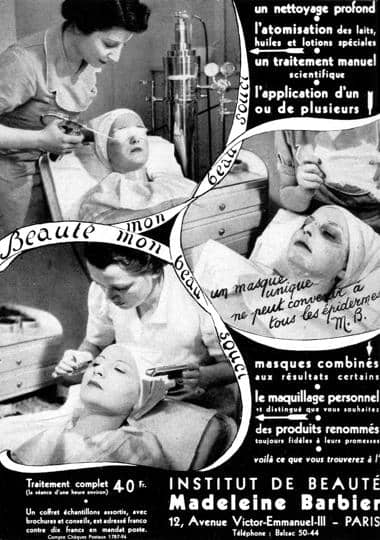

Believed to be developed and built by L.-B. Vautier in 1934, the Atomos unit consisted of a large tank of pressurised carbon dioxide attached to an atomiser. The Institut de Beauté Crès claimed to have been the first salon to have installed an Atomos unit but by the end of the decade they were found in a number of other Parisian salons including Klytia, N.-G. Payot, Madeleine Barbier and Guerlain.

The Atomos units required a larger capital outlay than the smaller hand-held devices introduced after the Second World War and were not as portable but had a number of advantages over the smaller units. The continuous inflow of pressurised carbon dioxide into the mixer flask meant that a wide variety of combinations of gas and liquid could be created; more gas and less fluid, more fluid and less gas. The unit was also more powerful than the later hand-held devices and was strong enough to apply an oil or a liquid cream should one be required.

Carbo-douche

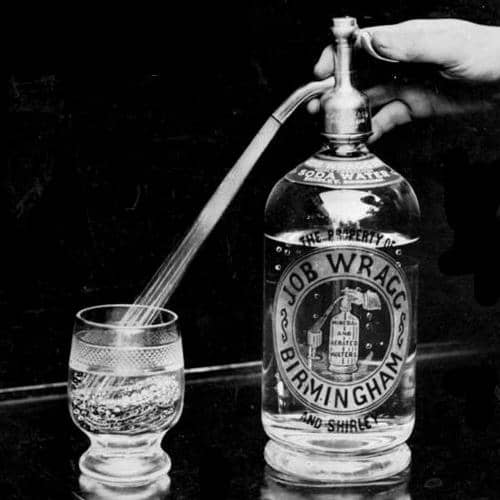

This hand-held device was the simplest type of carbonic gas spray. The carbon dioxide source came from cartridges also commonly used to make soda water in a soda siphon.

Above: Job Wragg Soda Siphon from the 1920s powered by a carbon dioxide cartridge.

Although the use of cartidges made the apparatus relatively expensive to operate in a salon, it enabled Socarb to advertise the unit for home use and the company also recommended it as a mouth spray to improve oral hygiene.

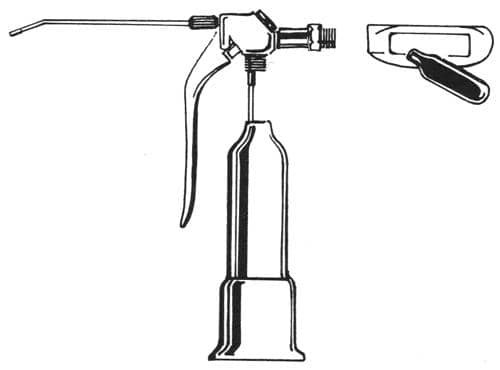

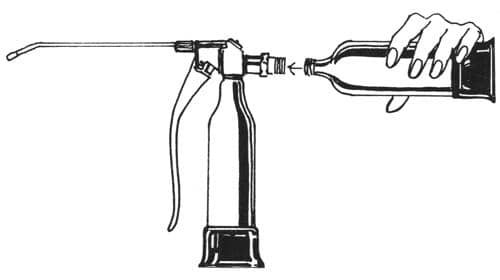

Above: Carbo-douche type device with carbon dioxide cartridge to be placed in the screw-on receptacle (Gerson, 1999).

Carbatom

The Carbaton device was also hand held but the device was charged by a tank of carbon dioxide rather than a cartridge.

Above: Carbatom atomiser with mixer flask, carbon dioxide cylinder and associated materials.

Above: Carbatom type device with screw-in carbon dioxide tank (Gerson, 1999).

When the tank ran out it was repressurised from a supply of carbon dioxide.

Above: Tank being refilled (Gerson, 1999).

The Carbatom was cheaper to run than the Carbo-douche which made it more popular in salons. However, it was not as convenient to recharge if used as a home appliance. Even so, as with the Carbo-douche, SERNO advertised the Carbatom for domestic use and also suggested that it could also be used to improve oral hygiene.

Treatment

Carbonic gas spray treatments should not be confused with carboxytherapy, an invasive medical treatment that injects carbon dioxide into the skin; or dry ice treatments, another medical procedure that sprays very cold carbon dioxide on the surface of the skin.

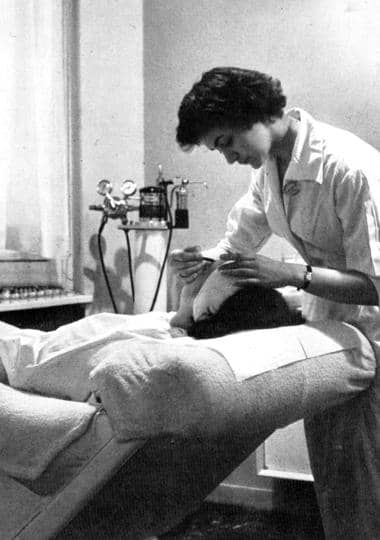

In the salon, most carbonic gas spray treatments were conducted on oily and acne prone skin and were generally employed after the skin was cleansed and extractions had been completed. However the treatment could also be used after make-up or a mask had been removed to help dislodged any residual material and refresh the skin. Due to its effect on blood vessels, vascular disorders such as rosacea were a contraindication.

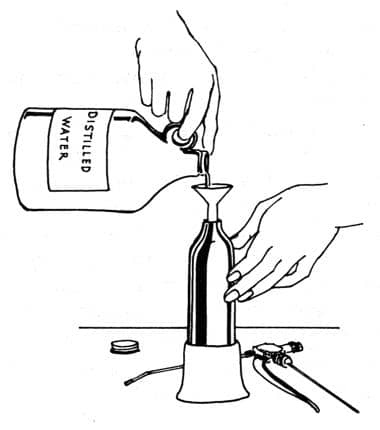

The spray is prepared by three-quarters filling the mixer flask with distilled water and any additional filtered ingredients, the most common additive being an astringent.

Above: Filling the mixer flask with distilled water (Gerson, 1999).

Like treatments with atomisers, a good deal of liquid could be generated during the procedure so clients were usually given a bowl to hold under their chin to catch falling water or had their chest covered with a towel. The force of the spray meant that the eyes needed to be shielded before the treatment began. As the eyes were covered and the spray was strong, the client had to be warned when the treatment was about to start and to expect to feel a tingling sensation. During the procedure the atomiser was held vertically some 20-30 cm away from the face and then the spray was administered across the face using circular motions. Excess material was then blotted off with tissues.

First Posted: 3rd October 2017

Last Update: 26th August 2021

Sources

D’Assailly, G. (1958). Fards et beauté ou l’eternal féminin. Paris: Librairie Hachette.

Gerson, J. (1999). Milady’s standard textbook for professional estheticians (8th ed.). Albany, NY: Thompson Learning.

Kovács, R. (1949). A manual of physical therapy (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger.

Martini, M.-C. (2012). Appareillages de pratique esthétique (2nd ed.). Paris: Lavoisier.

Carbon dioxide bath as used in a medical procedure (Kovács, 1949).

1938 Madeleine Barbier salon showing a number of treatments including one using a carbonic gas spray.

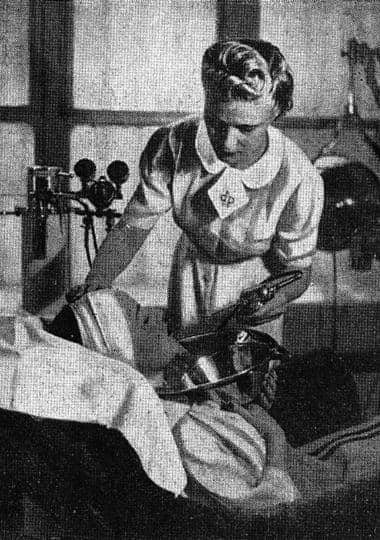

1939 Payot salon with a carbon dioxide atomiser in use attached to an Atomos unit. Payot referred to this treatment as ‘carborisation’ a term also used by Klytia and Guerlain when they introduced Atomos units into their salons.

1939 Klytia advertisement for carborisation treatments using an Atomos unit.

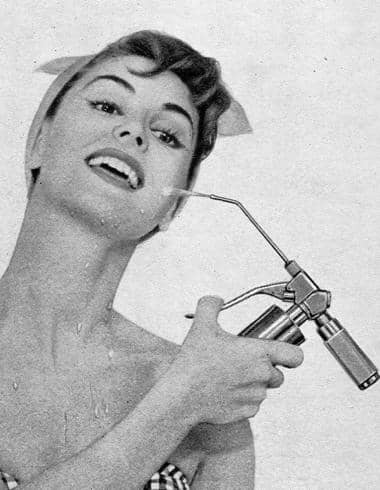

1951 Carbonic spray salon treatment. This is a publicity shot so the protective eye pads have been left off the model.

1956 Carbo-douche accentuating its use in oral hygiene.

1958 Atomos. The device is on wheels so that it can be moved more easily.

1958 Charles of the Ritz salon cubicle. There appears to be an Atomos unit at the back of the cubicle.

1958 Carbatom atomiser with filling flask and tank.

Model demonstrating a Carbatom being used in a bust treatment.

1962 Carbatom for use on the mouth face, and bust.

1962 Carbo-douche for a luminous complexion and healthy teeth and gums. Each device came with a complementary bottle of astringent.