The Ideal Face

In 1932, Max Factor unveiled his Beauty Calibrator, a device that measured how much a person’s facial features differed from the ‘perfect’ or ‘ideal’.

Above: 1933 Max Factor and Ern Westmore demonstrating the Beauty Calibrator. The subject is Dorothy Wilson [1909-1998].

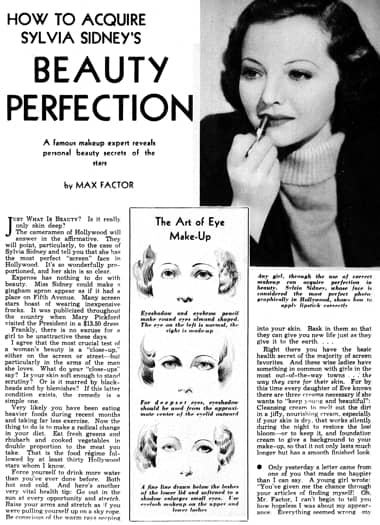

Screen players that had an ideal face – oval, well proportioned and symmetrical – had a good camera face, one that could be filmed from any angle. Few actresses were so blessed; Mary Pickford [1892-1979] was said to have one, and so did Sylvia Sydney.

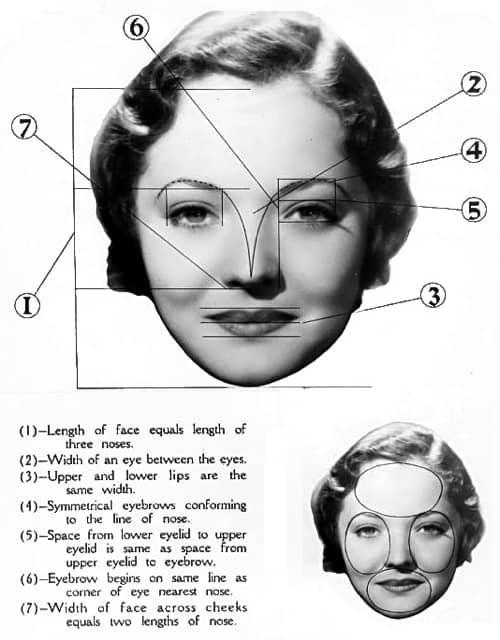

Above: 1934 Sylvia Sidney facial proportions.

The facial proportions listed for the ideal face are based on a Western model of beauty originating in Classical Greece which is still being used by artists and cosmetic surgeons to this day.

The ideal camera face, male or female, should be oval with features balanced symmetrically and arranged according to certain proportions. Vertically the face should be divided into three equal sections, horizontally into five eye widths. The mouth should be beautifully curved, slightly wider than the width of one eye. The upper lip should be a little fuller than the lower. Eyes should be large and open to brighten the expression; they should be an eye’s width apart.

(Annas, 1987, p. 52)

Westmore’s Corrective Make-up

Both Perc and Ern Westmore worked with the Beauty Calibrator and were familiar with the characteristics of the ideal camera face. Perc Westmore would use it as the basis for the Corrective Make-up system he developed at Warner Brothers–First National.

Within the past year, we have put into practice at the Warner Brothers’ studios a new system of makeup which we call “Corrective Makeup.” With it, we have been able to simplify the work of the cinematographer, and to greatly enhance the facial attractiveness of our stars.

(Westmore, 1935, p. 188)

Perc Westmore’s Corrective Make-up could be applied to men or women but the system was mostly used on actresses. In the early 1930s, thanks to the introduction of panchromatic film, male screen stars – when not in character or aged make-up – could generally get away with wearing little or no greasepaint.

Regardless of the player’s natural beauty, we have found that this system of makeup can be used to advantage, for even the most completely beautiful woman has some minor irregularities of contour which can be smoothed out in this fashion. The system can be applied with equal success to men, of course, but in practice, we rarely do so, as most of our male stars are of types which benefit by wearing little or no makeup.

(Westmore, 1935, p. 198)

See also: Panchromatic Make-up

Unlike men, movie make-up was not an option for women. By the 1930s, street make-up had become so commonplace that female stars were expected to wear it on and off the screen.

Planning Corrective Make-up

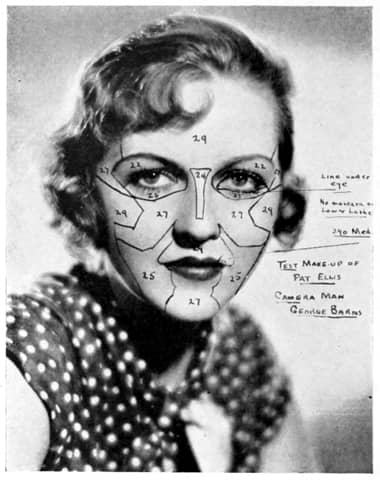

The first step in Perc Westmore’s Corrective Makeup was a facial examination. A make-up plan was then developed that would create the illusion that the actress had a face that was closer to the ideal.

Let us say that the lady has a face that is too round and full for our purpose, especially around the cheeks and chin; her nose is rather broad and flat; her lips are larger than we care for; her chin shows a pronounced dimple, and there are little hollows at the corner of her mouth which detract from the youthful effect. … Point No. 1 is, of course, to slenderize her face. This is done by using grease-paint several shades darker than the base makeup, and applying it at the hair-line, and under the chin – exactly as a good cinematographer would strive to maintain shadows in these same areas. Suppose the basic shade is a No. 25 grease-paint: these shadows might be painted with No. 29. The broad nose would be thinned by highlighting the ridge with a lighter paint – say No. 22 – and shadowing the walls of the nose with a darker shade – perhaps No. 27.

(Westmore, 1935, p. 188)

As Westmore noted, these make-up corrections relied on a general rule used by cameramen when lighting faces, that light brings features forward and shade recedes them.

We simply apply to makeup the same basic principles by which cinematograhers [sic] model faces with lighting: highlighting places that are undesirably recessed or concave, shadowing unpleasant protuberances. This is not done with liners or obvious tricks of coloration, but by carefully-planned use of different shades of regular grease-paint.

(Westmore, 1935, p. 188)

In fact, as Westmore himself noted, corrective make-up had to work in conjunction with lighting to be effective.

No possible combination of make-up can take the place of the cinematographer’s lighting. But correctly used, “corrective” make-up can supplement the cinematographer’s work, and make his problems easier.

(Westmore, 1937, p. 496)

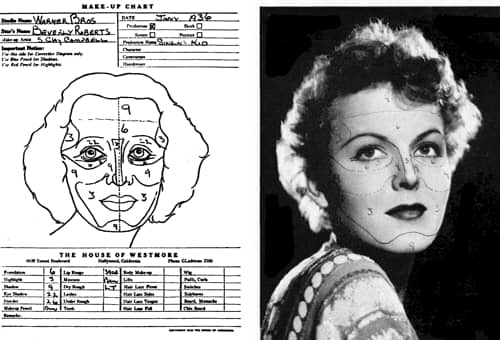

Once the corrective plan was developed, tested and approved, a sketch of the face was made showing the full make-up design. The completed sketch was then given a case number and filed for future use.

Above: Corrective make-up plan for the actress Beverly Roberts [1914-2009] (Westmore, 1937, p. 496).

Critics

Not all Hollywood make-up artists were enamoured with the idea of corrective make-up. As Jack Dawn [1892-1961] – head of the make-up department of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) – noted, ‘cosmetic painting’ had its limitations.

Our ultimate picture may be flat but our actor’s face isn’t. And the camera and actor both move around, so that the make-up is not regarded from one fixed viewpoint. Cosmetic painting can give a smooth texture to the skin, and a photographically even coloring at all points. As far as texture and color go, such make-up is good from all angles: but while our painted highlights and shadows can give an illusion of altered contour—if viewed from certain specified angles—they cannot be expected to do so from all angles or under all conditions.

(Stull, 1936, p. 374)

General make-up

Both Max Factor and the Westmores sold lines of general make-up and used their connection with Hollywood to promote them. Understandably, their make-up advice used techniques developed in Hollywood which were based, in part, on the principle of the ideal, oval face. The Westmores were still referring to it in the 1950s.

The oval face is recognized as the ideal, and the purpose of your make-up is to create the illusion of as perfect an Oval as possible.

(Westmore et al., 1956, p. 64)

The make-up techniques used by Max Factor and the Westmores to bring the face closer to the ideal would now be referred to as contouring. Max Factor called them ‘face shaping’ or ‘modelling with make-up’ while the House of Westmore stuck with Perc Westmore’s original term, ‘corrective make-up’. Max Factor usually limited his ‘face shaping’ advice to the eyes, cheeks and lips but the House of Westmore went further. Using a system of face shapes, the Westmores supplied women with corrective make-up suggestions for the overall shape of their face as well as its individual features.

See also: Face Shapes and Corrective Make-up (Contouring)

First Posted: 25th April 2018

Last Update: 10th November 2020

Sources

Annas, A. (1987). The photogenic formula: Hairstyles and makeup in historical films. In Maeder, E. (Ed.). Hollywood and history: Costume design in film (pp. 52-77). Los Angeles: Thames & Hudson/Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Basten, F. E. (1995). Max Factor’s Hollywood. Glamour, movies, make-up. Los Angeles: General Publishing Group.

Factor, M. (1934). How to acquire Sylvia Sidney’s beauty perfection. Hollywood, 23(5), May, 44, 59.

Stull, W. (1936). New make-up that is sculpture-like. American Cinematographer, 17(9), September, 374-375, 380-382.

Westmore, E., & Westmore, B. (1947). Beauty, glamour and personality. Sandusky, OH: Prang Company.

Westmore, E., Westmore, W., Westmore, B., Westmore F., & Westmore M. (1956). The Westmore beauty book. Chicago: Melvin Korshak.

Westmore, P. (1935). Corrective makeup as an aid to cinematography. American Cinematographer, 16(5), May, 188, 198.

Westmore, P. (1937). Cooperation works big in bulk of make-up. American Cinematographer, 18(12), December, 496-496.

Sylvia Sydney [1910-1999] regarded as having the ideal camera face.

1933 Max Factor’s Beauty Calibrator. Ern (Ernest) Westmore [1904-1968] helps Max Factor [1872-1938] make the adjustments while Perc (Percival) Westmore [1904-1970] takes down the readings.

Max Factor’s Beauty Calibrator. The device used screws to press flexible metal bands against the contours of the head so that facial features could be measured.

1934 Part of an article for the fan magazine ‘Hollywood’ written by Max Factor. In the article he describes how the reader can measure their face and compare this to the ideal.

“Take a ruler and measure the distance between your eyes. There should be the width of one eye between them.

The width of the face should be twice the length of the nose.

The upper lip ought to equal the lower one in size.

And the length of the face should be divided into three equal distances. From the top of the forehead to the bridge of the nose = from the bridge of the nose to its tip. and this, in turn, = from the tip of the nose to the chin.

Don’t get discouraged if these proportions come out wrong. Sylvia’s is one face in a thousand where they come out right. The only thing to do is to give them the appearance of being balanced.” (Factor, 1934, p. 59)

Corrective make-up plan for the actress Patricia Ellis [1918-1970] (Westmore, 1935, p. 188).

1937 Max Factor. How to apply rouge on a round face, a thin face, on high cheek bones, and on hollow cheeks. Note that rouge is applied on a round face to make it look more oval.

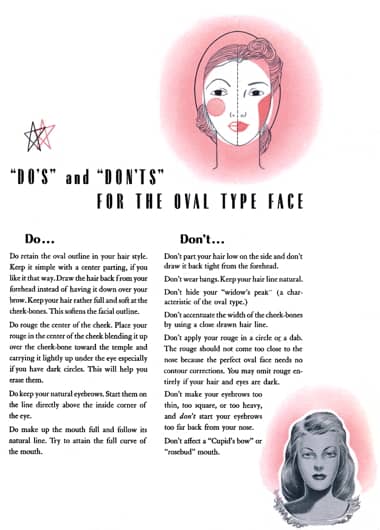

1947 Do’s and don’ts for the oval type face (Westmore & Westmore, 1947, p. 51). Even an ideal oval face needed to be made up correctly.