Eyelash Beading

In the days before the widespread adoption of false eyelashes, many actresses, dancers or others working in show business beaded their eyelashes to make them appear darker, fuller and longer. The practice persisted even after false eyelashes became commonplace and spread from the stage to the growing film industry until the arrival of the ‘close-up’ put a dampener on the technique.

Beading was cheaper than false eyelashes so was popular with chorus dancers who were generally not well paid. This is not to say that it was only practiced by those of limited means; when done with skill it could look very effective. Ethel Merman preferred beading to false eyelashes which, she thought, made her eyes look droopy.

Above: Ethel Merman [1908-1984]. Her beading technique does not appear to include adding a ball at the end of the lashes. To draw more attention to her eyes she has also raised her eyebrows.

See also: False Eyelashes

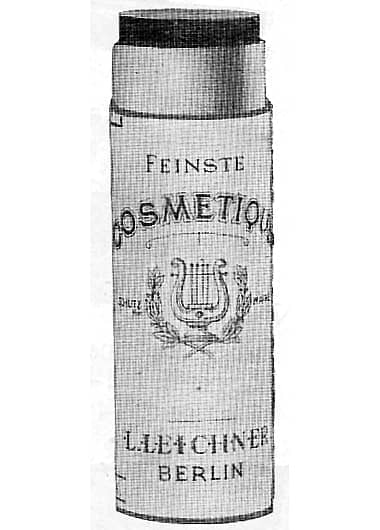

How far back the practice of beading extends is unknown to me but it probably started after the introduction of greasepaint in the later part of the nineteenth century and may have originated from the theatrical use of cosmetique to keep hair in place. Leichner suggests that his Cosmetique was originally developed as a hair fixative but it could also be melted in a spoon to darken the lashes.

See also: Greasepaint and Water Cosmetique

Beading technique

Eyelash beading requires a steady hand and more than a little practise to achieve a good result. It needs eyelash beading make-up, usually black or brown, a pan to melt it in, a heating element and an applicator – sometimes referred to as an eyelash-quill. The cash strapped did not need to spend money on a specialised pan, heater or applicator, as a spoon, candle and matchstick would do the trick just as well.

Although ordinary greasepaint could be used, there were a number of theatrical suppliers that made beading make-up including Paramount, Mehron, Stein, Leichner and Max Factor using the names ‘Beadex’ (Mehron), ‘Alpine Cosmetic’ (Stein), ‘Heating Cosmetic’ (Leichner), ‘Eye-Lash Beading’ (Max Factor) and ‘Black Cosmetique’ (Roger & Gallet).

When doing the beading, a small quantity of the make-up was placed in the pan and heated until molten. Then, taking small amounts at a time, the melted make-up was applied to the lashes with the flat end of an orange stick, or something similar, to cover the lashes and leave a little bead hung on each lash tip. In many cases the makeup was also used to stick lashes together to make them more prominent.

All the time Rachel was trying experiments with my face, Miss Fay, still ignoring us completely, proceeded to “make-up” her eyes. This was a most fascinating process. First, she held a battered-looking spoon filled with black cosmetic over the gas jet. As the cosmetic melted, it filled the room with a sickly odor of cheap perfume or burning grease. When it was melted to the consistency of a thick soup, she scouped [sic] it up on a short, pointed stick and applied it to her lashes in such a way that when it cooled it left a large lump of cosmetic at the end of each lash, and made her look as if she had strung black beads around her eyes. While she decorated her right eye she stretched down the left corner of her lower lip, [sic] and vice-versa, as if to balance her face, for, of course, any movement of the eye-lids would cause the hot cosmetic to splash down on her cheek and ruin her make-up. I made up my mind to do my eyes like this the first chance I had.

(Wemple, 1904, p. 106)

The practice was also used by some early film stars such as Viola Dana.

Last came her eyes, and I watched closely, for Viola Dana’s eyes are most fascinating both on and off the screen. First she brushed the lashes upward and darkened her lids slightly. Taking a match stick, she lit it and burned the tip off till it was pointed. Then she melted some cosmetic on the end of it and held it downward until it formed into a little bead. When it was cool she applied it to her lashes and then with a hairpin separated each lash.

The finished work was most satisfactory to the beholder. Her eyes looked marvelous! Her lashes are extraordinarily long and curly, and when beaded they turned back and up until they touched her eyebrows—honestly!(Sands, 1922, p. 86)

Beading was not without its critics.

Leichner makes a special “Heating Cosmetic” for adding glamour to the lashes, in blue, brown and black, which has to be melted in a spoon or tin lid held over a candle flame, and can then be applied with a fine brush or matchstick. There is also an Eye Cosmetic (mascara) for darkening the lashes, which will not smear and does not smart, if by chance any gets into the eyes.

Each lash should be treated separately, on the under side only, and it is not always necessary to carry the colour right to the roots, unless the lashes are naturally very fair, nor should they be clogged with paint, and large lumps or ‘beads’ of grease-paint on the ends of the lashes (another temptation!) should be avoided, as they sometimes give the eyes a cross-eyed effect.(Melvill, 1957, p. 33)

Fire risk

The presence of a naked flame in a theatre is always a risk. In 1937, Joan Bergere, a member of the Cole Brothers-Clyde Beatty Circus, received first-degree burns after her tulle netting ballet skirt caught fire on a candle used to melt eyelash-beading make-up. Theatre safety officers were supposed to insist on these candles being placed in a container such as a cosmetic stove to minimise the risk of fire but this must have been difficult to police when large casts and numerous dressing rooms were involved.

Above: Lockwood Cosmetic Stove. The parts all fitted together to make it easy to carry. The pan contains some beading mixture.

In this place we are going to tell you how to bead the eyelashes, but unless you are a professional actress and your part will be decidedly enhanced by having the eyes very much in evidence, we advise against your undertaking it. It is not a necessary stage in the makeup process, but it comes into the story of makeup naturally and we give it here for the benefit of those who may wish to make use of it. Beading the lashes consists in placing a small bead of cosmetique on the extreme tip of each lash. This is best done on the upper lashes only, leaving the lower ones free. The Lockwood Cosmetic Stove is a small affair that holds a piece of candle and a baby-size frying-pan, or skillet, and is one device for its purpose that has the approval of fire insurance companies and so will not be objected to by the theatre fireman.

(Wayburn, 1925, p. 159)

The introduction of electrically heated pans reduced the fire risk but burns were still possible.

Above: Max Factor eyelash beading kit. The heating source and pan have been combined in the electrical unit which was much safer than using an open flame.

Extent of use

Eventually the practice moved beyond show business and was picked up by some more adventurous women. Dancers would go on elsewhere after shows, some still made up, enabling their make-up to be seen, discussed and emulated. The practice must have had some general following, as its use was still being discouraged by beauty advisors as late as the 1960s.

Mascara should be applied to the upper and lower eyelashes if they need it. The fine comb should always be used top separate the hairs after the coloring dries. The application should never be conspicuously heavy; beading the eyelashes is not to be done except in theatrical make-up.

(Wall, 1961, p. 496)

There is no need to repeat this advice today. Inexpensive, good-quality false eyelashes and greatly improved mascaras have made the practice redundant. However, if you are looking for that ‘genuine call-girl look’, it might be worth the effort. For safety sake, I would follow Alida Valli’s example and do it on a set of false rather than your own eyelashes.

First Posted: 1st June 2011

Last Update: 12th December 2023

Sources

Corson, R. (1967). Stage Makeup (4th ed.). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

L. Leichner artists catalogue. (c.1926). London: Houghton & Sons.

Melvill, H. (1957). Magic of make-up. London: Rockliff.

Sands, E. (1922). A fan’s adventures in Hollywood. Picture-Play. New York: Street & Smith Corporation.

Wall, F. E. (1961). The principles and practice of beauty culture (4th ed.). New York: Keystone Publications.

Wayburn, N. (1925). The art of stage dancing. New York: The Ned Wayburn Studios of Stage Dancing Inc.

Wemple, J. (1904). Confessions of a stage struck girl. The Theatre: An illustrated magazine of theatrical and musical life. 4(38) 103-106.

Whorf, R. B. (1937). Time to make up: A practical handbook on the art of grease paint. Boston: Walter H. Baker Company.

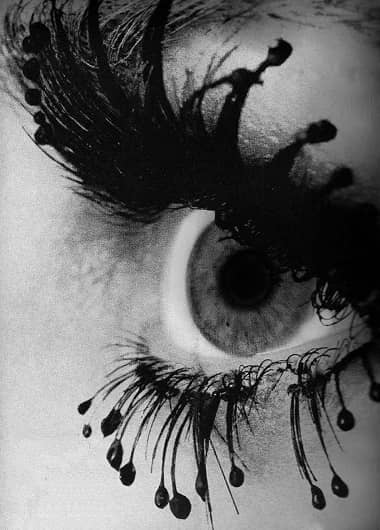

Eyelash beading used in the ‘Tears’ photograph by Man Ray a.k.a Emmanuel Radnitzky [1890-1976]. The eyelashes are clumped together into groups and finished off with a small bead on the end of the lash.

c.1926 Leichner Cosmetique. “This was originally introduced as a Fixateur for keeping the hair in place and may be successfully employed for that purpose if required. Melted in a spoon LEICHNER’S COSMETIQUE is a splendid medium for darkening the eyelashes. SHADES: Black, Silver, Neutral” (L. Leichner artists catalogue, c.1926, p. 21).

A Stein’s eyelash beading kit from an early twentieth century make-up box of a male actor. A heat source and an applicator would also have been needed.

1925 Ned Wayburn Stage Dancing Make-up kit. The item maked ‘K’ in front of the mirror is a ‘Lockwood Cosmetic Stove’ used to heat the beading cosmetic. “For heating cosmetique to bead the eyelashes. This stove is approved by Fire Insurance Underwriters. It encloses a candle in a safe way and avoids the use of dangerous fuels in the dressing rooms.”

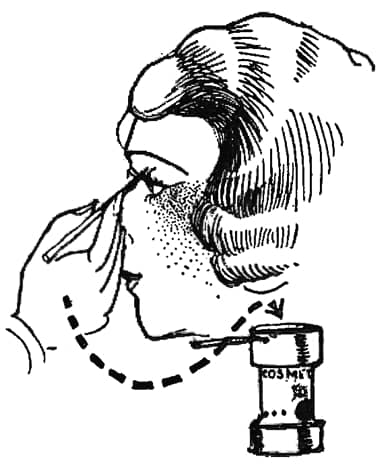

Explanatory drawing of eyelash beading using make-up melted in an alcohol stove (Whorf, 1937, p. 9).

Viola Dana a.k.a. Virginia Flugrath [1897-1987] with lashes that appear to be beaded. It would be interesting to know whether she continued the practice after she started endorsing Maybelline.

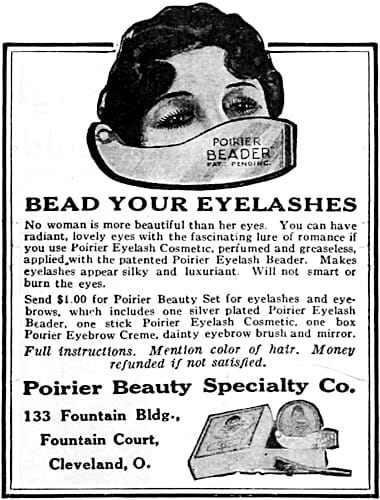

1921 Poirier eyelash beader.

1935 Arlette Bernard Cosmecil (France). The mascara advertisement uses the Man Ray photograph.

Eyelash beading on false eyelashes by Alida Valli a.k.a. Baroness Alida Maria Laura Altenburger von Marckenstein-Frauenberg [1921-2006] in the film ‘The Third Man’ (British Lion Film Corporation, 1949). She is peeling them off in the lower photograph.

1969 An example of beaded false and real eyelashes done at the height of the 1960’s fashion cycle in false eyelashes (modified from Vogue).