Elizabeth Arden

Continued to: Elizabeth Arden (1920-1930)

Like her long-term adversary, Helena Rubinstein [1871-1965], any account of early life of Florence Nightingale Graham – later known as Elizabeth Arden – suffers from a lack of reliable records and a great deal of prevarication by Arden herself. A good example of this is the date of her birth. Arden lists this as 1883 on her 1915 marriage certificate and 1886 on her 1920 passport application. However, although her birth record seems to have disappeared, census records and a statutory declaration by her older brother, William Pearce Graham [1877-1959] both put the date at 1881.

The much copied Lewis & Woodworth write that Florence grew up on her parent’s small farm in Woodbridge, Ontario, Canada. However, like her date of birth, this appears to be another fabrication. Florence’s father, William Graham [1849-1928], is listed as a bookkeeper on the 1873 birth record of her older sister Christine Graham, with the family living at 129 Church Street, Toronto; as a grocer on the 1875 birth record of her older sister Lilian and the 1877 birth record of her older brother William, with the family living at 401 and 472 Yonge Street, Toronto respectively; and as a peddler on the 1884 birth record of her younger sister Jessie Gladys Graham with the family living on the Town Line in Vaughan. This suggests a life mostly in ‘trade’ rather than farming and declining prospects at that. However, it does not completely exclude the idea that he rented a small piece of land and peddled the vegetables he grew on it, so the stories about Florence watching her father haggling with women over the price of vegetables (Lewis & Woodworth, 1973, p. 34) may have some validity.

Whatever his employment, William Graham appears to have been of limited means so the Graham children only received a basic education and were put to work as soon as possible. Adding to the family problems, the five siblings were left motherless when Susan Pearce Graham (nee Tadd) [1844-1888], died from tuberculosis at a relatively early age.

If the Graham children were not brought up on a farm then Arden’s much recounted interest in horses and horse racing may have come from tending the animal that pulled the cart her father used when peddling, rather than one necessarily connected to a plough. Also, occasional mentions of Arden working as a bookkeeper (Lewis & Woodworth, 1973, p. 43) may be references to her father’s early employment rather than any skill on Arden’s part. Perhaps the only firm ground in all of these early narratives is her father’s alcoholism.

Like her childhood records, verifiable accounts of Florence’s early adult life are also scarce. Lewis & Woodworth provide stories from this time as well but these are mostly used to demonstrate some aspect of Florence’s ‘developing genius’ so should also be treated with a degree of scepticism.

According to Lewis & Woodworth, Florence worked in Toronto as a bank teller, a secretary in a real estate company and then as a dental assistant (Lewis & Woodworth, 1973, p. 39), the last position giving them an opportunity to describe an early example of Florence’s business acumen.

By 1907 she was working as an assistant to a dentist. The job paid better than anything she’d had up to that point. When she wasn’t handling him his instruments, she was taking care of his books. One look at his accounts, and she knew that the position would not last long unless she did something about drumming up some new business. She hit upon an idea that was very daring in its time.

Florence bombarded his patients with letters graphically describing what would surely happen to their teeth, if they didn’t come to see the dentist very soon. His business doubled within a year. It was her first crude stab at what would one day be called her genius for public relations.(Lewis & Woodworth, 1973, p. 40).

Lewis & Woodworth also write that Florence starting training as a nurse in Toronto but abandoned this after realising that she did not like the sight of blood or dealing with ill people. There she supposedly met a biochemist who got her interested in skin creams. This led to her attempt to “mix up a batch of instant beauty” (Lewis & Woodworth, 1973, p. 38) on the kitchen stove. This story signals Florence’s early interest in cosmetics and chemistry and gives her some medical/scientific training. Like Rubinstein’s claim to have once enrolled to become a doctor, all this is likely invented.

Lewis & Woodworth then suggest that when Florence joined her brother William in New York she got a job as a bookkeeper for the pharmaceutical company, E. R. Squibb and Sons. There, they relate, she continued to pursue her “intense interest in chemistry” (Lewis & Woodworth, 1973, p. 44). The idea that Florence could get working access to a Squibb laboratory or that she had any knowledge of chemistry makes this story the least plausible of all.

Eleanor Adair

Leaving all the above to one side we get on slightly firmer but still muddied ground in 1908 when Florence took a position with Eleanor Adair [b. c.1864]. Adair operated a beauty salon at 15 West 39th Street, New York in addition to others in London, Paris and elsewhere.

Florence’s job at the Adair salon has been variously listed as cashier, receptionist and secretary but whatever her role she apparently learnt how to apply the various treatments offered by Adair so it is possible that she was originally hired as a trainee treatment girl. Florence would later disparaged Adair but a study of her early beauty products and salon treatments reveals the deep debt she owes to her.

See also: Eleanor Adair

In 1909, Eleanor Adair relocated her New York salon to 21 West 38th Street. The year also marked the beginning of Florence Graham’s transformation into Elizabeth Arden. After coming to an arrangement with another Beauty Culturist, Elizabeth Hubbard, the pair opened a salon on the third floor of the Walton Building, a brownstone at 509 Fifth Avenue. The business alliance between the women was short lived and Florence was soon left holding the lease on a beauty salon with the name Elizabeth Hubbard in gold lettering emblazoned on the third floor window.

Florence decided to keep the name Elizabeth but had the sign-writer remove the surname and replace it with Arden. The commonly reported inspiration for the new surname is a poem by Tennyson called ‘Enoch Arden’ but Woodhead suggests that Florence got the name from reading about the Orange County estate of the railroad baron Edward Henry Harriman [1848-1909] which was called Arden (Woodhead, 2003, p. 94). Harriman’s death in September, 1909 was widely reported in newspapers and this may have bought the Arden name to Florence’s attention. However, both suggestions for the origin of the surname are speculative at best.

Of greater interest is the unanswered question about how Florence managed to finance her new business after Elizabeth Hubbard departed. Lewis & Woodworth write that Florence borrowed US$6,000 from her brother William Graham but, as Woodhead points out, neither William nor any of Florence’s siblings would have had the funds for a loan of this magnitude (Woodhead, 2003, p. 95). Money may have come from another relative but it is possible that, like Helena Rubinstein, Florence was backed by an admirer and kept quiet about it.

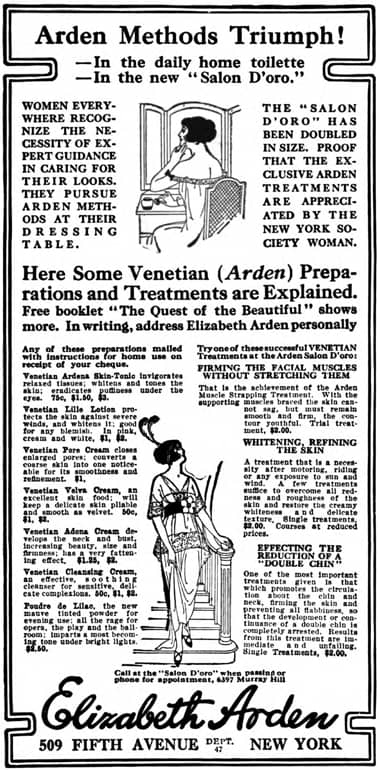

Salon d’Oro

Florence named her new beauty establishment the Salon d’Oro. To help with the lease she persuaded the hairdressers Jessica Ogilvie [1885-1943] and her sister Clara Ogilvie [1887-1950] into moving into one of the larger rooms. The arrangement brought additional customers to the Salon d’Oro and, in return, the Ogilvie sisters got cheaper rent.

The business was a success from the day it opened but it is difficult to pinpoint exactly why this was the case. Her position on Fifth Avenue and the arrangement with the Ogilvie sisters would have helped but it seems clear that Florence – whom I will now refer to as Elizabeth Arden – was skilled at giving treatments – had ‘good hands’ – and selling her cosmetics. Lewis & Woodworth write that Clara Ogilvie later exclaimed, “The way she could sell! And the way she could train other girls to sell—it was astonishing!” (Lewis & Woodworth, 1973, p. 57). If Florence’s father was a pedler observing him in operation – for better or for worse – might be the source of her ability to sell.

One of her early treatment girls appears to have benefited from this training. When Dorothy Cloudman [1886-1968] was dismissed by Arden for reportedly ‘living in sin’ she responded by opening her own salon and product line under the name Dorothy Gray. She would incur Arden’s life-long enmity for this, Arden conveniently overlooking that this is what exactly what she had done to Eleanor Adair.

See also: Dorothy Gray

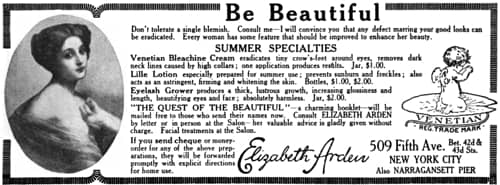

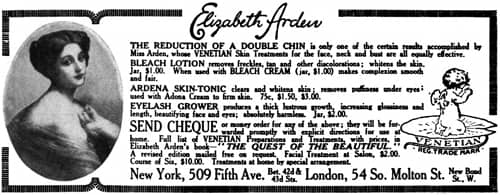

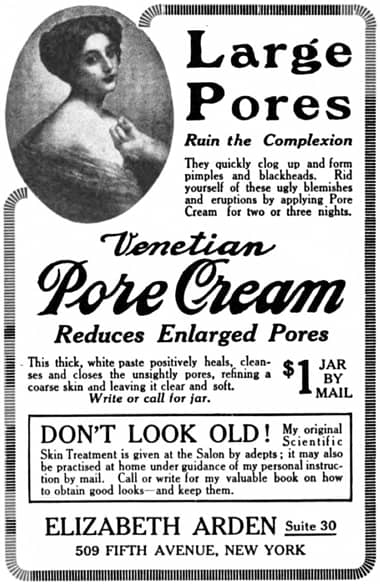

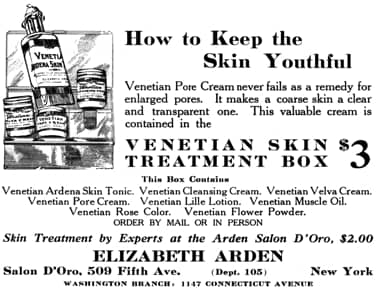

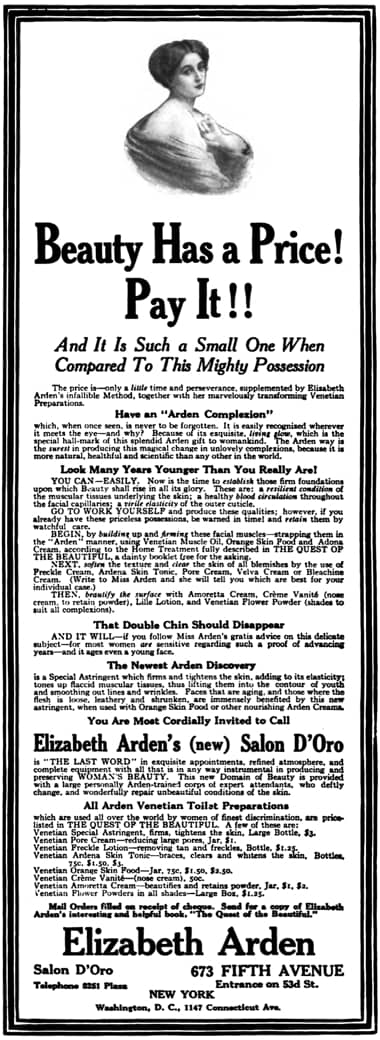

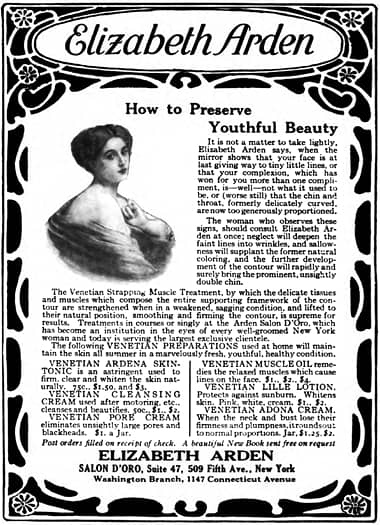

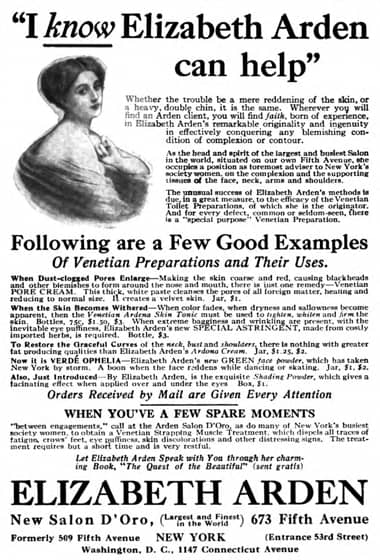

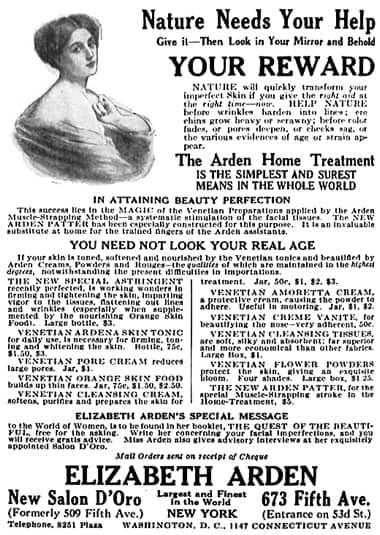

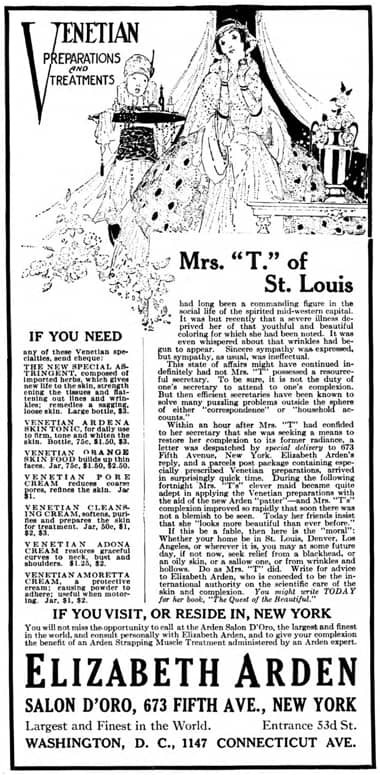

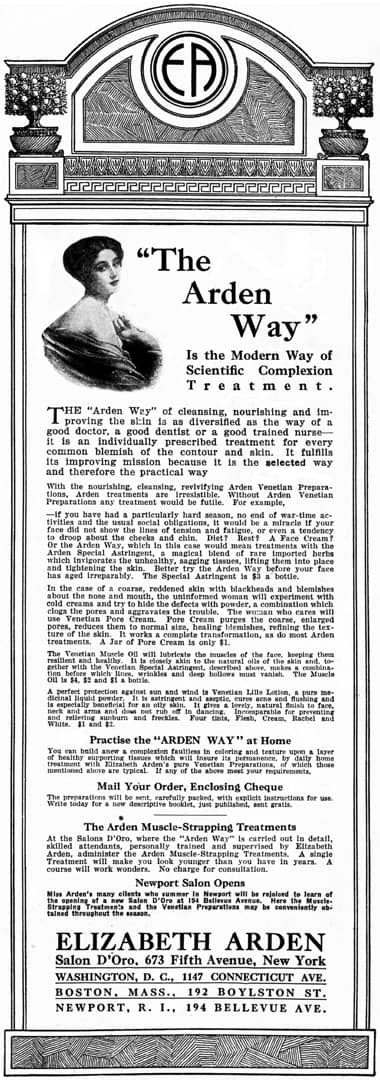

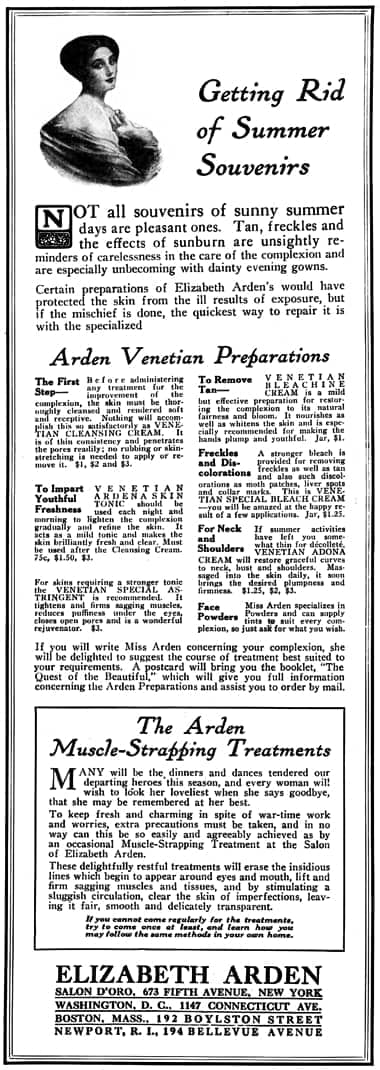

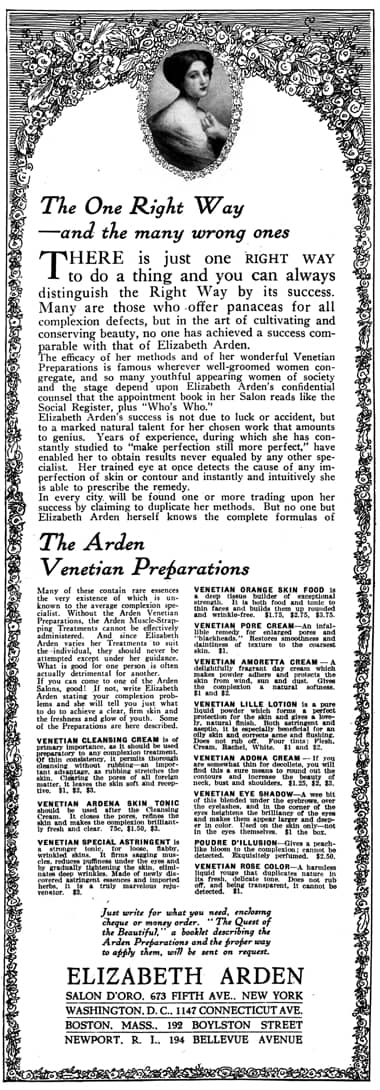

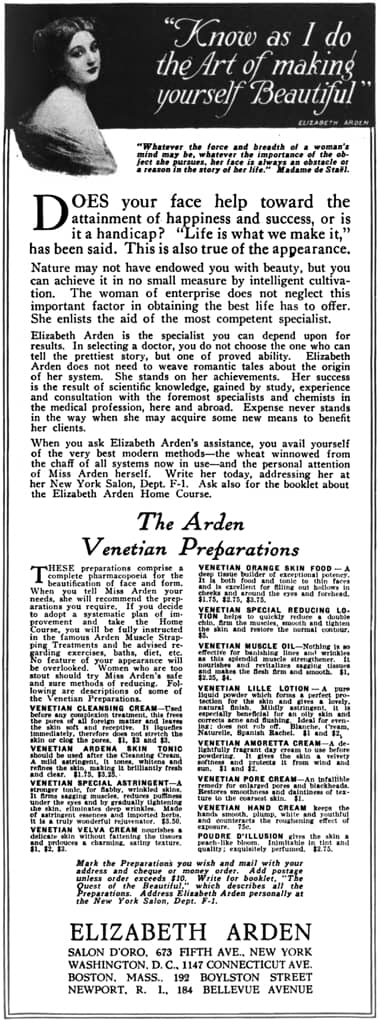

Advertising also helped Arden to grow her business. She spent considerable sums in promoting her salon and cosmetics in magazines and newspapers very early on and this practice contributed to the continuing success of her business.

Above: 1911 Elizabeth Arden.

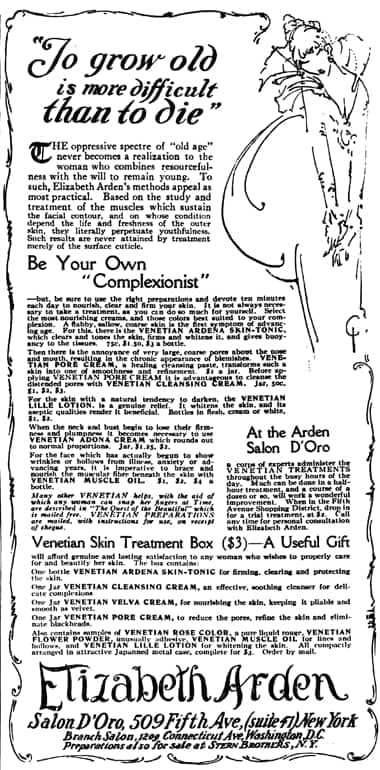

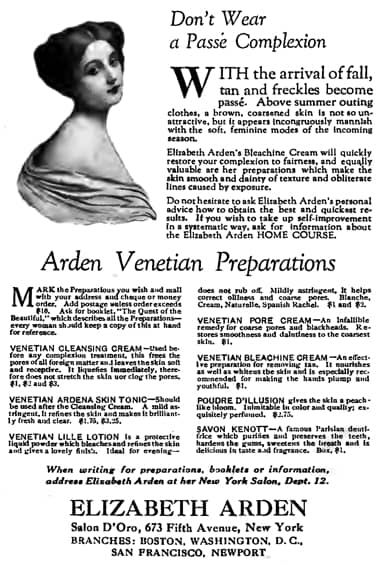

Starting in New York, the newspaper advertisements soon extended across the United States inviting women to purchase her cosmetics by mail-order. Advertising her cosmetics in this way enabled Arden to use her Fifth Avenue address to promote her products to a much wider market which helped bring in much needed cash. A lot of her early national advertising was restricted to one or two products, such as Venetian Pore Cream and Venetian Eyelash Grower, with Arden adjusting her subsequent advertising by the orders she received.

Florence Delaney

Amongst the treatment girls and support staff that Arden hired early on was Florence G. Delaney [1881-1949]. Arden nicknamed her Lanie (Laney) perhaps to avoid confusion over their shared first name. Biographers of Elizabeth Arden all give Delany’s first name as Irene but the name change was never legally confirmed.

According to later newspaper reports, Arden hired Delaney in 1912 as a bookkeeper but census records indicate Delaney had previous experience in sales which would have been useful. She rose to become treasurer of Elizabeth Arden, Inc. in 1931 and was made director and treasurer of the Elizabeth Arden Sales Corporation in 1933 in addition to her role as manager of the New York salon. She never married and was one of the few employees that stuck with Arden over the long term.

Paris and London trip

In the summer of 1912, Arden felt confident enough to leave her salon in the care of others and make her first trip to Europe. There she toured the beauty salons of Paris and London looking for new products and treatments in much the same way that Helena Rubinstein had done in 1905. She probably avoided the Paris and London salons of Eleanor Adair but it seems very hard to believe that she did not include a visit to at least one of Helena Rubinstein’s Maisons de Beauté Valaze, either at 255 Rue Saint-Honoré in Paris or at 24 Grafton Street in London.

See also: Helena Rubinstein

During her tour of the salons Arden bought perfumes and cosmetics to take home for analysis and took note of the way Parisian women made more use of make-up than was considered acceptable in the United States at the time. On the way home, her event-packed trip was capped off with a shipboard romance with Thomas Lewis. Arden would eventually marry him in November, 1915.

Thomas Jenkins Lewis

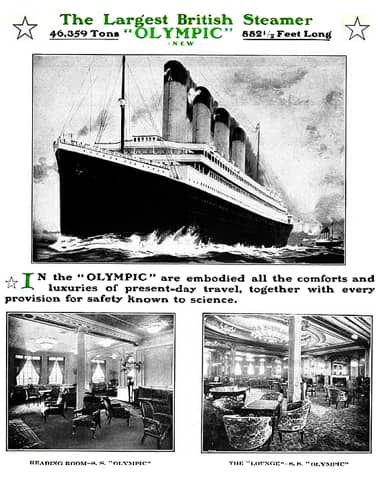

Woodhead (2003) suggest that the shipboard romance with Tom Lewis occurred on the S.S. Caronia. A Florence Graham was on board that ship but the record shows her travelling with an older Mary Graham and there is no sign of Thomas Lewis being on board.

It seem more likely that the two met on the S.S. Olympic which sailed from Southhampton on 29th August, arriving in New York on 5th September, 1912. Thomas J. Lewis was on board as was an Elizabeth Arden, described as 5ft tall with dark skin, dark hair and blue eyes. She is listed as born in Toronto but more importantly, her home address was given as 321 West 94th Street, New York, the same address listed for Florence N. Graham in the 1915 New York Street directory. There is also an entry for an E. Arden born in Canada sailing first class on the S.S. Lapland from New York to Dover, arriving 21st July, 1912.

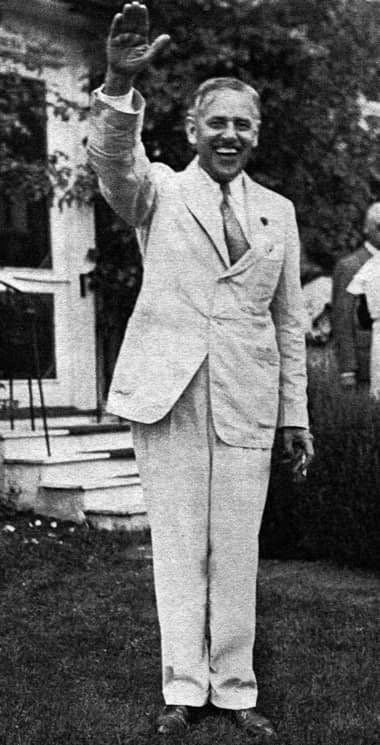

Why Tom Lewis was crossing the Atlantic on the S.S. Olympic is unknown to me. Lewis & Woodworth – who incorrectly state that the two met on the S.S. Lusitania in 1914 – write that Arden had already met Tom Lewis when she applied for a bank loan to to expand her business (Lewis & Woodworth, 1973, pp. 63-64) but provide no explanation for him being on board. Woodhead (2003) notes that if Tom Lewis was the bank clerk described by Lewis & Woodworth, he would not have earned enough to afford a ticket. She suggests he was a ‘silk salesman’ who has been visiting Macckesfield, the centre of England’s silk-weaving business (Woodhead, 2003, p. 100). However, an examination of census records indicates that Tom Lewis did work in banking. His occupation is listed as bank examiner (1900), bank cashier (1905), banker (1910) and accountant (1915) – the last entry being some months before he married Arden – so there may be some truth in Lewis & Woodworth’s version of events after all. His financial experience also helps explain his success in managing Arden’s growing business empire after the two were married in November, 1915.

Expansion

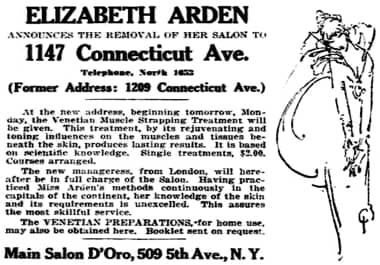

In 1913, with her business doing well, Arden rented more space at 509 Fifth Avenue which doubled the size of her salon. In 1914, she opened a second Salon D’Oro at 1209 Connecticut Avenue, Washington D.C., moving it to 1147 Connecticut Avenue in December that year. By then, she had also convinced Stern Brothers – a department store on 42nd Street – to stock her cosmetics with Bonwitt Teller following soon afterwards.

Above: Stern Brothers department store.

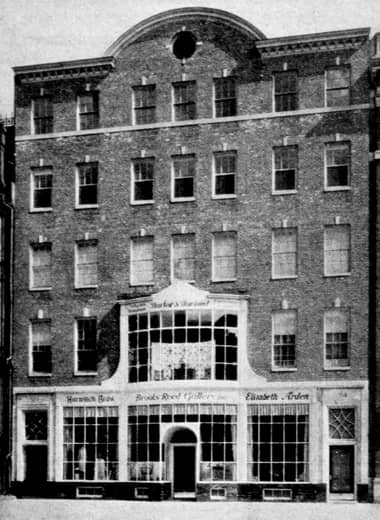

In September, 1915, Arden relocated her New York salon to 673 Fifth Avenue and the Ogilvie sisters moved to 505 Fifth Avenue. The Walton Building, the site of Arden’s first salon, was marked for demolition – replaced by a twelve-story office building that still stands today. The move was timely. In May, 1915, Helena Rubinstein had opened her first American Maison de Beauté Valaze at 15 East 49th Street, New York to great acclaim. The move allowed Arden to advertise her new establishment as ‘the largest salon in New York’ and claim a more fashionable Fifth Avenue address.

Above: The building on the right of this block is 673 Fifth Avenue. Arden moved her salon there in 1915. It had a private entrance on 53rd Street. The photo was taken in 1923 (Museum of the City of New York).

Between 1915 and 1920, Helena Rubinstein opened American salons in New York, San Francisco, Chicago, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Boston and Atlantic City. In the same period, Arden added salons in Boston (1915), San Francisco and Palm Beach (1919), and Detroit (1920). By this time, Arden was receiving a considerable amount of help from her husband, Thomas Lewis. He was more congenial than Arden, a good salesman and his skills and affability helped establish Arden’s American wholesale business on a sound footing (Woodhead, 2003, pp. 139-141).

Salon treatments

As might be expected, the early Elizabeth Arden beauty treatments were based on what Arden had gained from Eleanor Adair. The signature treatment of Arden’s Salon D’Oro was Muscle-Strapping, largely a copy of Eleanor Adair’s Strapping Electrical Treatment. Arden’s version appears to have left out the electrical part of the facial routine, perhaps because it would have required her to spend money on a galvanic battery and the associated electrical leads. She would not have been able to help offset this expense with electrolysis treatments, something for which she had neither the training nor, I suspect, the temperament.

Also see: Electrolysis

Like Adair’s Strapping Electrical Treatment, Arden’s Muscle-Strapping Treatment combined massage movements to improve circulation, strengthen muscles and reduce fatty tissue, with straps to lift and improve facial contours.

The Arden Treatment smooths out lines and wrinkles; lifts up sagging muscles and flabby skin; firms, whitens, refines its texture; restores outline of youth; produces bloom and color by stimulating circulation; removes blemishes and reduces pores; reduces double-chin—and in all ways, creates and restores beauty of skin and contour.

(Elizabeth Arden advertisement, 1915)

Arden also adopted Adair’s view that massage could stretch the skin which could lead to wrinkles so, like Adair, she used finger patting and vibratory massage in her facial routines rather than broad massage strokes.

Elizabeth Arden realized that massage stretches the skin, causing it to droop and wrinkle. She straightway abandoned all massage and evolved her famous Muscle-Strapping Method which does nor stretch the skin a particle but stimulates the tissue to a healthy firmness. It builds up wasted tissue, prevents wrinkles and crowsfeet, molds the contour, eliminates even the thought of ever looking passé.

(Elizabeth Arden, 1920, p. 4)

The patting and strapping was combined with a range of skin-care cosmetics – astringents to lift and tone the muscles, and skin foods and muscle oils to feed the underlying tissues – again ideas taken directly from Adair.

See also: Skin Tonics, Astringents & Toners, Skin Foods and Muscle oils

Straps and Patters

Women could replicate the muscle-strapping treatments they received in the Salon D’Oro at home by purchasing the necessary cosmetics and equipment. Arden published numerous informational booklets on how to conduct home treatments, most of her early booklets given the title ‘The Quest of the Beautiful’.

See the company booklet: The Quest of the Beautiful (1920)

Eleanor Adair sold chin straps and forehead straps for home facial treatments and a Domino Strap for puffy areas under the eyes. By 1920, Arden was selling versions of all of these types of straps with an elbow strap added for good measure.

Venetian Chin Strap: “[M]ade from the finest imported silk webbing, and scientifically constructed to hold the muscles of the face and neck just right. To remove and prevent a double chin it is the perfect appliance.”

Arden Chin Strap De Luxe: “[T]hickly padded with powerful astringent herbs, which shrink the fat or flabby tissues, lift the sagging muscles, and take years from the appearance.”

Venetian Forehead Strap: “[B]ands the forehead in such a way as to smooth out those persistent lines and wrinkles on brow and at the corners of the eyes.”

Venetian Puffy-Eye Strap: “[F]or removing lines and puffiness under the eyes.”

Arden L-Bow Strap: “[A] clever and much needed appliance to make homely elbows beautiful.”

See also: Straps, Bandages and Tapes

The finger-tapping procedure used in combination with the facial straps could also be replicated at home using a patter. Eleanor Adair sold one and Elizabeth Arden copied this with the Arden Venetian Patter.

Arden Venetian Patter: “[A]n ingenious device, invaluable for the Muscle Strapping Treatment. Its use in the Home Treatment is almost as good as the personal treatment given by an expert in my Salon. … [W]onderful in getting rid of a double chin, firming the facial muscles and the skin and, best of all, helping to maintain the contour of the face and neck.”

See also: Patters

Products

Elizabeth Arden branded her products as Venetian to distinguish them from Elizabeth Hubbard’s Grecian range. The previously mentioned Dorothy Cloudman, a.k.a Dorothy Gray, did the same, badging her cosmetic range as Russian. As a point of interest I note that Eleanor Adair sold a skin bleach she called Venetian Cream. This may have been why Arden added Adona to her Venetian Adona Cream even though it was a ‘skin food’ not a bleach.

Like Helena Rubinstein, it has often been said that, at first, Arden made the cosmetics herself in one of the rooms of her salon. However, it seems more likely to me that, like Rubinstein, she simply sourced her cosmetics in bulk from a drug house like Park-Davis & Co. and that her ‘laboratory’ labours consisted of filling and labelling bottles, and then packaging items ordered by mail for posting.

A. Fabian Swanson

Whatever the early situation, this changed with the entrance of Axel Fabian Swanson [1897-1956] more usually known as A. Fabian Swanson. Swedish born, Swanson was a Doctor of Philosophy graduate from Brown University employed as a chemist by Stillwell & Gladding, Inc., a New York firm which operated an independent testing laboratory.

It seems likely that Arden came into contact with Swanson when she sent some of the cosmetics she had collected on her 1912 European trip to Stillwell & Gladding for analysis. Swanson continued to be associated with Stillwell & Gladding until at least 1919 but he also worked for Arden formulating cosmetics in the laboratory she set up in the Frances Building at 665 Fifth Avenue, New York in 1915. Like Florence Delaney he was also a loyal employee, remaining with Arden for the next 40 years.

The first cosmetic Swanson is credited with developing for Arden was a ‘light, fluffy cream’ named Venetian Cream Amoretta. Released in 1915, it was marketed as a powder base which suggests it may have been a type of vanishing cream, possibly a ‘snow’. Snows used carbonates or bicarbonates in their formulation which released carbon dioxide during the manufacturing process giving the vanishing cream a foamy consistency.

See also: Vanishing Creams

Swanson is often said to have followed the Cream Amoretta with Ardena Skin-Tonic – a simple solution of water, ethyl alcohol, boric acid and fragrance (Phillips, 1934, p. 62). However, this cannot be the case as Ardena Skin-Tonic was available no later than 1913, two years before Cream Amoretta came on the market. It, or something very similar, would also have been an essential preparation for Arden’s muscle-strapping treatments so was probably used in her salon from day one. It is possible that the Ardena Skin-Tonic has been confused with Venetian Special Astringent which came onto the market in 1915 along with Venetian Orange Skin Food.

Skin-care

Early Arden Venetian skin-care preparations included all the basics required for a muscle-strapping treatment: a cleansing cream, a skin tonic, and a range of ‘tissue builders’. In addition, she also sold a number of commonly retailed preparations such as a mild skin bleach – reportedly containing lemon juice – and a pore cream, the later preparation being the one Arden most frequently advertised early on for purchase by mail-order.

Venetian Cleansing Cream: “[A] lovely, smooth cream that liquifies quickly, taking every particle of dust and foreign matter out of the pores. the fact that it liquifies so quickly prevents any stretching of the skin whatsoever.”

Venetian Ardena Skin-Tonic: “A mild astringent, a real tonic for the skin … It is effective for toning, firming and whitening the skin naturally, imparting smoothness and brilliance to the complexion.”

Venetian Velva Cream: “[N]ot a fattening cream, but a delightful refining cream made especially for dry or tender skin requiring gentle, nourishing treatment.”

Venetian Adona Cream: “A deep tissue builder, rich in fat producing qualities. Will round out the contour of the neck, fill up hollows in front of the shoulders, and develop the bust.”

Venetian Muscle Oil: “[E]xcels all other preparations in nourishing and restoring the virility of the facial muscles. … This magic oil feeds and fills out sunken features, softens mature lines and wrinkles about the mouth and eyes, and firms and strengthens the entire face.”

Venetian Bleachine Cream: “A mild bleach and a smoothing, fattening cream all in one.”

Venetian Pore Cream: “[R]educes the pores till the skin has an exquisite satiny quality.”

Later additions to the Venetian line included the previously mentioned Venetian Special Astringent and Venetian Orange Skin Food as well as Venetian Special Bleach Cream in single and double strengths.

Venetian Special Astringent: “A clever compound of astringent essences, extracted from rare imported herbs. Its use is to firm and tighten the skin and add to its elasticity. It tones and lifts flaccid muscles, wonderfully improving the contour.”

Venetian Orange Skin Food: “[A] deep tissue builder of unusual potency and high nutritive value to rebuild worn and flabby tissues and promote the active glands of the skin.”

Venetian Special Bleach Cream: “[W]ill diminish and remove freckles, moth patches, liver spots, collar marks and other skin discolorations, from face neck and hands.”

These skin-care cosmetics were used in the morning and evening routines Arden recommended as home treatments.

BEDTIME TREATMENT—At night a film of dust clogs the pores of the skin. It must be removed. Make a firm pad of absorbent cotton, squeezed out of cold water, dip in the Ardena Skin Tonic, then in cleansing Cream.

“Wash” the face and neck with this. Always apply with an upward movement—never to encourage the tissues in their down-sagging.

Dry the face with Cleansing Tissues.

Another pad of absorbent cotton, squeezed out of cold water, can be fastened to the Arden Patter with a rubber band. Dip it in the Skin Tonic (sometimes in Special Astringent, if a stronger tonic is needed) and pat the face and throat—gently—for five minutes.

Dry again with Cleansing Tissues. Pat Orange Skin Food lightly over the face—with the fingers this time.

Over the Skin Food apply Muscle Oil on the lines of the facial muscles—about the eyes, forehead, lines from the nose to mouth, in front of the ear, and under the chin. After ten minutes of this patting, leave what remains on the skin to be absorbed during the night by the stimulated hungry cells.

For a full face, use Velva Cream, as it is not fattening.IN THE MORNING the facial exercise commences in the same way. The cleansing with the Cleansing Cream and the patting of the Ardena Skin Tonic awakes the tissues to normal, healthy functioning.

Pat on Velva Cream or Orange Skin Food, depending upon the skin requirements. Pat with the fingers for five to ten minutes and then remove with Cleansing Tissue.

Make a firm pad of absorbent cotton, squeezed out of cold water. Saturate with Ardena Skin Tonic, flop over the entire face and neck to thoroughly drench the skin. Pat for a few minutes, then quickly smooth a piece of ice over the face, wet the face with Skin tonic again dry with Cleansing Tissue.

Next apply Lille Lotion to protect the skin. Moisten a pad of absorbent cotton first in cold water, then dip it in Lille Lotion. Pat on very lightly, smooth off with cleansing tissues as if using a blotter. If Lille Lotion is too thick, dilute with Ardena Skin Tonic.

If you prefer a cream for daytime use, smooth Amoretta Cream evenly over the face until only a film is visible.

If too pale, dip a little Rose Color on a moistened pad of absorbent cotton. Apply to the cheeks and tip of the ears, blending it carefully.

Lightly apply the exquisite powder selected for your coloring, after which brush the eyebrows and eyelashes carefully.

Use a little Venetian Lip Paste if necessary, the Eye Shadow to elongate the eyes, and the Venetian Cosmetique for the eyelashes.(Elizabeth Arden, 1920, pp. 8-9)

Arden also sold cosmetics for specific skin-care problems such as freckles, enlarged pores, blackheads, acne and eczema.

Venetian Freckle Cream: “[R]emoves sunburn and freckles.”

Venetian Beauty Sachets: “An antispetic healing lotion of invaluable assistance in freeing the skin of pimples, spots and other eruptions, and quickly relieves irritations caused by acne and poison ivy.”

Venetian Acne Lotion: “An antispetic healing lotion of invaluable assistance in freeing the skin of pimples, spots and other eruptions, and quickly relieves irritations caused by acne and poison ivy.”

Venetian Cream for Eczema: “An unusually effective cream to soothe, benefit and in many instances entirely heal the eruptions caused by eczema.”

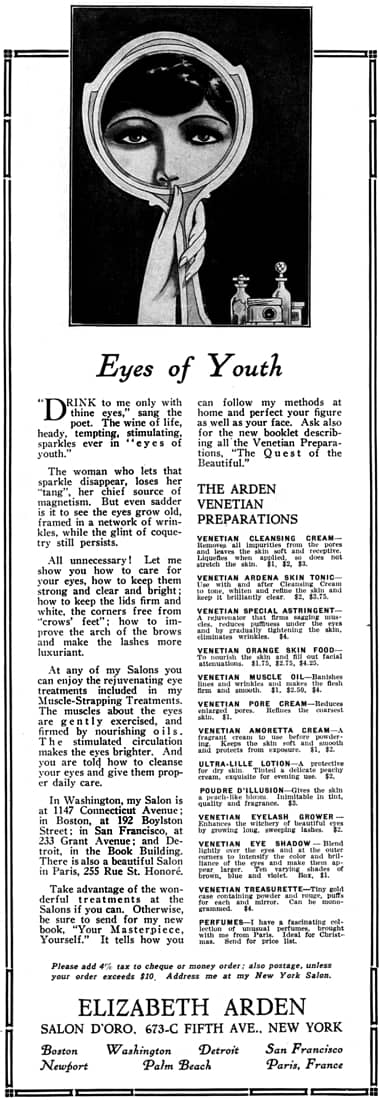

Eye treatments

Arden had a number of products specifically aimed at improving the eyes and the eye area, many of which were available in 1910. Like her other early skin-care cosmetics these appear to have been based on similar preparations used by Eleanor Adair for whom eye treatments were a speciality.

[Miss Arden] knows the most important secret about looking young and beautiful, the proper way to treat the muscles around the eyes to maintain their mobility and firmness, preventing that sunken appearance, wrinkles and puffiness&mdash the real enemies of beauty. Miss Arden is very particular to advise her clients how to keep the eyes strong, clear, bright and the skin around the eyes smooth, firm and young.

(Elizabeth Arden, 1920, p. 21)

The previously mentioned Puffy-Eye Strap could help ‘remove deep lines and puffiness under the eyes’ and ‘numerous tiny lines caused from eyestrain’. To build up the muscles around the eyes, Arden recommended Venetian Special Eye Cream but also suggested adding a few drops of Muscle Oil to it in the morning treatment. For tired eyes, clients could use a Venetian Eye Bandelette steeped in hot water. This was laid over the eyes for about five minutes then replaced with absorbent cotton squeezed out in iced water. Clients could also use Venetian Crystalline Eye-Drops and/or Venetian Special Eye Tonic, an eye bath.

Venetian Special Eye Cream: “[A] superfine tissue cream to nourish the delicate tissues and muscles around the eyes.”

Venetian Eye Bandelettes: “[A]n excellent treatment for dark shadows, tired or puff eyes.”

Venetian Special Eye Tonic: “[C]omforts and strengthens the eyes when they are tired and aching. … [U]sed morning and night with an eye cup. Its unusual tonic effect has in many cases overcome the necessity for glasses.”

Venetian Crystalline Eye-Drops: “[R]emoves all irritation and discoloration from the ‘white’ of the eye.”

Hands and nails

Arden’s only hand preparation in the period up to 1920 was Venetian Hand Cream.

Venetian Hand Cream: “[S]plendid for the hands as they require protection as well as the face, being in constant contact with roughening or irritating substances.”

Women wanting to whiten their hands as well could use the previously mentioned Venetian Bleachine Cream applied overnight under rubber Venetian Retiring Gloves. By 1920, Arden also sold cloth Arden Superbe Mits that were pulled over the hands and arms up to the elbow after the application of Crême Glacier. This was put on warm but hardened when it cooled suggesting that it may have contained paraffin wax.

Crême Glacier: “[W]armed and permitted to harden on the skin under the Arden Superbe Mit of softest fabric. A splendid treatment for modeling and beautifying the hands and arms.”

See also: Paraffin Wax Treatments

At some stage after the First World War, Arden also introduced Venetian Enamel which I assume was a clear or slightly pink, transparent nail polish.

Other products

After the Ogilvie sisters and Arden went their separate ways Arden added hair products to her range and, by 1920, these included shampoos, tonics, pomades, dandruff preventatives and hennas.

Other products in the Venetian range by 1920 included: Savon Kenott, a French toothpaste brand; June Geranium Soap; a range of bath salts; Venetian Snowdrift (1918), a talcum powder; and Venetian Odeursans, a deodorant. Arden also sold two hair removers, Venetian Dermatex Depilatory (1916), a sulphide powder depilatory to dissolve hair, and Venetian Electra Eradicator, a hot wax treatment that pulled the hairs out by the roots.

Venetian Dermatex Depilatory: “It removes the down of the face, or the coarse hair under tha arm, in five minutes, harmlessly.”

Venetian Electra Eradicator: “Much more effective than the usual depilatory. A substance composed of tested ingredients on a wax base, for removing, hair from the face. A single treatment banishes the offending, hairs and weakens the roots.”

See also: Chemical Depilatories

Make-up

If used with discretion, both powder and rouge were becoming more acceptable in the New York in the early part of the twentieth century and Arden sold both early on, specifically Venetian Flower Powder and Venetian Rose Color. Her 1912 Paris visit appears to have stimulated a greater interest in make-up leading to the introduction of eye make-up in 1914 followed by the development of lip cosmetics and a wider range of face powders and rouges.

Foundations and powders

The early shade range of Arden’s first face powder, Venetian Flower Powder, is unknown to me but, by 1920, it was sold in Blanche, Cream, Naturelle, Special Rachel (light brunette), Spanish Rachel (dark brunette) and Rose. Other face powders added by then included: Poudre de Lilac (1913), a mauve-tinted powder for evening use; Poudre Vert Ophelia, later replaced by, or renamed as Venetian Poudre Olivâtre, a greenish powder used to tone down a florid complexion; Poudre Maréchal Neil (1916), another evening powder for women with a white skin; Poudre De Soir (1916), for day and evening use; and Poudre D’Illusion (1916), a more expensive day powder. All these later additions only came in a single shade in 1920.

Venetian Flower Powder: “An exquisitely fine light powder.” Shades: Blanche, Cream, Naturelle, Special Rachel, Spanish Rachel, and Rose.

Poudre de Lilac: “[M]auve tinted powder for evening use; all the rage for the opera, the play and the ballroom; imparts a most becoming tone under bright lights.”

Poudre Maréchal Neil: “[F]or evening use, it is particularly good as it enhances the quality of the complexion and makes the skin clear, bright and transparent.”

Venetian Poudre Olivâtre: “[P]recisely the tint with which to tone down an unusually high color or florid complexion, under sun or artificial light.”

Poudre De Soir: “[A] fine delicately tinted powder for day or evening, adhering imperceptibly to the skin and lending It a soft bloom.”

Poudre D’Illusion: “A particularly wonderful day powder made especially for those who demand the extreme of quality and exclusiveness.”

Arden also added a range of compact powders which, by 1920, came in Blanche (White), Illusion, Naturelle and Rachel shades.

Making powder stick to the skin was a problem for many early face powders. The addition of Venetian Amoretta Cream (1915) gave Arden her first powder foundation. This was followed by Venetian Ultra-Amoretta which contained a higher proportion of oil so was better suited for dry skin types. Venetian Creme Mystique was also recommended as a powder foundation but specifically for the nose to help reduce shine. It came in a flesh color so it also acted like a concealer to reduce any sign of redness or blemish.

Venetian Amoretta Cream: “It is a valuable aid to those who have difficulty in retaining powder on the face.”

Venetian Ultra-Amoretta: “Amoretta plus just enough oil to make it a good powder foundation for an unusually dry skin.”

Venetian Creme Mystique: “[R]ecommended for covering red and shiny noses and for rendering blemishes less noticeable. … Apply lightly and dust with Flower Powder.” Shade: Flesh.

See also: Loose Face Powders

Another early make-up item was a liquid powder called Venetian Lille Lotion. Initially marketed a skin protectant, and a sunburn and freckle preventive, it was said to possess aseptic qualities so was probably formulated with calamine, a common practice of the time. Used as an evening wet white on the face, neck and arms, like most liquid powders of its type it was very resilient. Originally made in Pink, Cream and White tones, a Spanish Rachel shade was added by 1920 by which time Arden was also selling a creamier version, Venetian Ultra-Lille Lotion, for dryer skin types.

Venetian Lille Lotion: “[A] medicinal liquid powder which is good for the skin. It removes blemishes; acts as an astringent; possesses aseptic qualities and is a perfect protection agains sun, wind and freckling.” Shades: Pink, Cream and White.

Venetian Ultra-Lille Lotion: “It has twice the thickness of Lille lotion and contains sufficient oil to give a smooth, soft texture to even a dry skin, defying any appearance of lines and wrinkles.” Shades: Naturelle, Cream, White. and Spanish Rachel.

See also: Liquid Face Powders

Rouge and Lipstick

Initially, Arden only stocked a liquid rouge, the previously mentioned Venetian Rose Color, but she later added cream and compact (dry) rouges. Depending on the compact model, the dry rouge came in Ash Blonde, Titian, Decided Blonde, Light Brune, Dark Brune, Medium or Brunette shades.

Venetian Rose Color: “A smart rouge in liquid form, just the right thing if natural color is slow in returning.”

Venetian Rouge Amoretta: “A superfine cream rouge that gives a beautiful soft, natural glow to the cheeks.”

For the lips woman could use either Venetian Lip Paste or Venetian Arden Lip Pencil. Both cosmetics only came in two shades: Star, a brownish red and Carnival, a deep red. There was also Venetian Indelible Lip Pencil for evening use, made indelible with a fluorescein dye.

Venetian Lip Paste: “[I]mparts a natural color to the lips. Just a tiny bit of it tipped on the fingers make the lips uniformly lovely in color.” Shades: Star and Carnival.

Venetian Arden Lip Pencil: “[A] lipstick that does not rub off and one that gives a smart natural tone to the lips.” Shades: Star and Carnival.

See also: Lipsticks and Indelible Lipsticks

Eye make-up

Arden sold her Venetian Eyelash Grower very early on, although whether this could be called make-up is debatable. Amongst the eye make-up inspired by her 1912 Paris trip, that she introduced in 1914, was a brown Venetian Shadow Powder later renamed Venetian Eye Sha do. Eyebrows could be groomed with an Eyebrow Brush and Special Tweezers, and coloured with a Venetian Eyebrow Pencil. Eyelashes could be darkened with Venetian Eyelash Cosmetique, a cake mascara, applied with an Eyelash Brush.

Venetian Eyelash Grower: “[P]roduces a thick, lustrous growth, increasing glossiness and length, beautifying eyes and face; absolutely harmless.”

Venetian Eyelash Cosmetique: “Pale lashes, even when they are heavy, lack character and distinction, while dark lashes lend mystery and charm to the eyes.” Shades: Brown, Dark Brown and Black.

Venetian Eyebrow Pencil: “A penciled brow is like an accented word It ‘points up’ the face.” Shades: Black and Brown.

Venetian Eye Sha-Do: “[S]imulates eye shadows to perfection, and is used on the lids to elongate the eyes.” Shade: Brown.

Overseas expansion

By the end of the decade Arden’s American business was well established as was her animosity to Helena Rubinstein. The next step was to move overseas.

Above: 1911 Elizabeth Arden available from stores in South Molton Street and Bond Street, London. This is the only advertisement I have found like this so the arrangement with these outlets may have been still born or short lived.

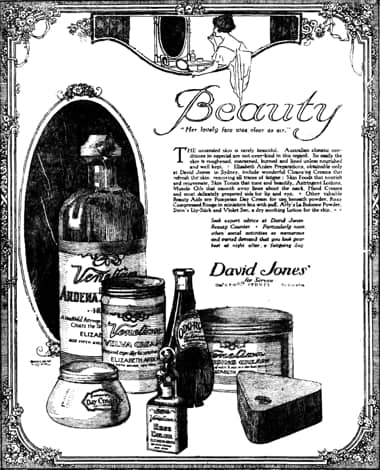

There are some references to Arden products being sold in London as early as 1911 but, as yet, she had no salons there. Beginning in 1920, Arden began establishing salons in Britain and Europe, and opening accounts with department stores there. Other places were not forgotten. It must have been particularly satisfying when her products began to be sold in Australia, the place where Helena Rubinstein got started.

Timeline

| 1909 | Florence Graham and Elizabeth Hubbard open a salon at 509 Fifth Avenue, New York. |

| 1910 | Florence Graham goes into business for herself at 509 Fifth Avenue, New York, as Elizabeth Arden. New Products: Venetian line. |

| 1913 | New Products: Poudre de Lilac. |

| 1914 | Second salon opened in Washington, D.C. New Products: Venetian Shadow Powder. |

| 1915 | New York salon moved to 673 Fifth Avenue. Salon opened in Boston. Laboratory established at 665 Fifth Avenue, New York. New Products: Venetian Amoretta Cream; Venetian Special Astringent; Venetian Special Bleach Cream; and Venetian Orange Skin Food. |

| 1916 | New Products: Venetian Bleachine Cream; Poudre de Soir; Poudre Maréchal Neil; Poudre D’Illusion; and Savon Kenott. |

| 1918 | New Products: Venetian Snowdrift. |

| 1919 | Salons opened in San Francisco and Palm Beach. New Products: Venetian Ultra-Amoretta. |

| 1920 | Salon opened in Detroit. Paris salon opened at 255 Rue Saint-Honoré. |

Updated: 18th April 2019

Continue to: Elizabeth Arden (1920-1930)

Sources

Allen, M. (1981). Selling dreams: Inside the beauty business. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

Elizabeth Arden. (1920). The quest of the beautiful [Booklet]. USA: Author.

Lewis, A. A., & Woodworth, C. (1973). Miss Elizabeth Arden. London: W. H. Allen.

Peiss, K. (1998). Hope in a jar: The making of America’s beauty culture. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Shuker, N. (1989). Elizabeth Arden. Cometics entrepreneur. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Silver Burdett Press.

Woodhead, L. (2003). War paint. Miss Elizabeth Arden and madame Helena Rubinstein their lives, their times, their rivalry. London: Virago Press.

Florence Nightingale Graham [1881-1966] a.k.a. Elizabeth Arden.

Florence Graham in the family home in Ontario, Canada.

Florence Graham (right) with Eve Elkins and Bart Howich. None of early photographs of Florence are taken on a farm.

1913 Elizabeth Arden Venetian Ardena Skin-Tonic, Venetian Lille lotion, Venetian Pore Cream, Venetian Adona Cream, Venetian Cleansing Cream and Poudre de Lilac.

1913 Elizabeth Arden Venetian Pore Cream.

1914 Elizabeth Arden, Washington, D.C.

1914 Elizabeth Arden.

Frances Building designed by the architect Charles Pierrepont Henry Gilbert [1861-1952]. Completed in 1912, Arden opened her first laboratory here in 1915.

1936 Elizabeth Arden in her office with a woman who might be Florence Delany.

The S.S. Olympic.

Thomas Jenkins Lewis [1875-1971].

1915 Elizabeth Arden Beauty Box.

1915 Elizabeth Arden.

1915 Elizabeth Arden.

1915 Elizabeth Arden announcing the move of her salon.

Elizabeth Arden Salon d’Oro at 24 Newbury Street, Boston. The door to the salon is on the right.

1916 Elizabeth Arden.

1916 Elizabeth Arden.

1916 Elizabeth Arden.

1916 Elizabeth Arden.

1916 Elizabeth Arden Venetian Preparations and Treatments.

1917 Elizabeth Arden.

Elizabeth Arden dressed like the idealised woman used in her advertising.

1917 Elizabeth Arden.

1918 Elizabeth Arden.

1919 Elizabeth Arden.

Arden trademark. First used in 1910, this design was widely used on Elizabeth Arden Beauty Cases and occasionally on product labels such as Venetian Waterproof Cream.

1919 Elizabeth Arden Home Course.

1919 Elizabeth Arden.

1920 Elizabeth Arden.

1920 Elizabeth Arden Eyes of Youth. Arden cosmetics are now available in Paris, France.

1920 Elizabeth Arden Venetian Preprations with a range of other cosmetics on the beauty counter in the David Jones department store, Sydney, Australia.