Leichner

Continued onto: Leichner (1910-1945)

Ludwig Leichner was a German opera singer best known for the theatrical greasepaint his firm, L. Leichner, developed in the late nineteenth century.

Leichner was born in Mainz, Germany in 1836. His parents – Ludwig Leichner [1802-1859] and Henriette Katharina, Jakobina Leichner née Bach [c.1809-1859] – both died in 1895, and this seems to have allowed him to pursue his desire to become an opera singer. In 1859, he moved to Vienna where he sought the counsel of the composer Heinrich Proch [1809-1878] who advised Leichner to train with Alexander Arlet [c.1821-1875] of the Imperial Opera School in Vienna.

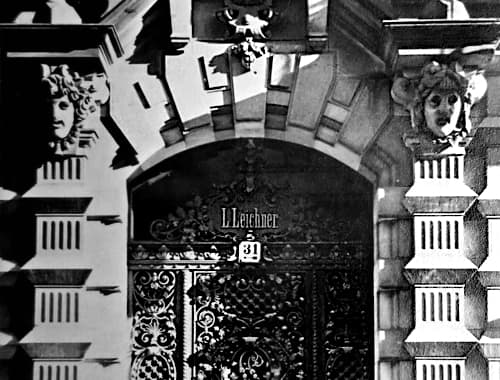

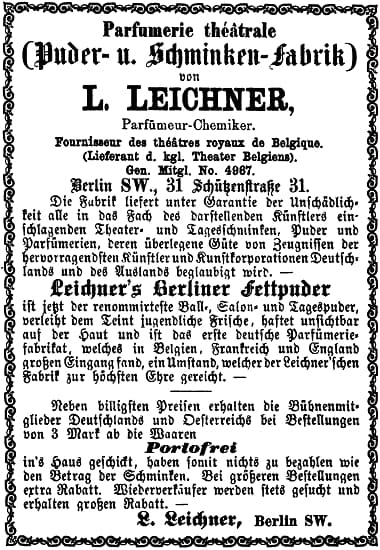

In 1863, after completing his training with Arlet, Leichner left Vienna and embarked on his career as an opera baritone under the stage name Rafael Carlo. He performed in places such as Freiburg, Bramberg, Budapest, Lemberg, Linz, Magdeburg, Stettin, Konigsberg, Cologne, Wuzburg, Zurich and Berlin. Exactly when he gave up his singing career is contentious. Some have put this at 1873, the year he founded his Puder- und Schminken-fabrik business at Schützenstrasse 31 in Berlin. However, Gellert (1891), Eisenberg (1903) and others put his retirement at 1876, some three years later.

By the time he started the business in Berlin, Leichner was married and had fathered three children. There is an 1870 marriage certificate for Ludwig Leichner and Leopoldine Jünger [1837-1914] but the 1889 version of Gesellschaft von Berlin records the marriage taking place in 1865. Germany was not unified until 1871 so it is possible that the couple had to register their marriage in different states as Leichner moved between opera engagements.

Gesellschaft von Berlin also lists the couple as having two children, Gustav Adolf and Jacob Rafael Friedrich, but does not include their birth dates. This may be because records have Gustav being born in Vienna in 1860, suggesting either, that Leopoldine was not his birth mother or that Gustav was born out of wedlock with the couple living together in Vienna unmarried. Jacob Rafael Friedrich Leichner arrived in 1866, followed by Siegfried Leichner in 1889. Siegfried’s birthdate is surprising as Leopoldine would then have been in her early fifties.

Leichner is often said to have developed greasepaint through a good understanding of chemistry. This is contentious. He may have began studying pharmacy or chemistry in Mainz before deciding to become a singer (Gellert 1891). Gellert, who appears to be writing from the Leichner company playbook, also claims that Leichner attended lectures in chemistry at the University of Vienna and worked in chemical-pharmaceutical laboratories there (Gellert, 1891, p. 1) while studying to become a singer. Others have suggested that Leichner was employed in a more modest workplace, namely the Mohren-Apotheke (Berliner Leben, 1911).

Above: Mohren-Apotheke at Wipplingerstrasse 12, Vienna after it moved from Tuchlauben 27 in 1906.

The connection between Leichner and chemistry is supposed to have continued after Leichner left Vienna. He was said to have studied chemistry during a three-year engagement at the State Theatre in Wuzburg in the laboratory of Professor Johannes Wislicenus [1835-1902] (Gellert, 1891; Eisenberg, 1903) and followed this with a further three years in Berlin under Professor August Wilhelm von Hofmann [1818-1892].

It is hard to believe that Leichner worked extensively with either of these famous chemists. It seems more likely that Leichner consulted chemists for advice on making stage make-up rather than undertaking a course of instruction. At the time, Germany had a vibrant chemical industry that was, in many ways, more advanced than France, Britain or the United States. Links between German universities and industry were also strong so it would have been natural for Leichner to consult with the university in Wuzburg for assistance. Having received support from chemists in Wuzburg, Leichner would have looked for similar help from chemists at the university in Berlin to solve any problems that arose after manufacturing had begun.

Once he had perfected his theatrical make-up, Hartnoll (1967) suggests that Leichner and his wife began making the greasepaints at home for Leichner and his fellow singers, perhaps as early as 1870, before growing demand saw Leichner decide to go into commercial manufacturing. In 1873, he opened a factory at Schützenstrasse 31 in Berlin and established the firm of L. Leichner. Where he got the funds for this is unknown to me.

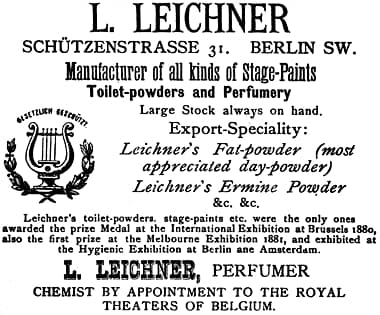

Initially, Leichner products would have had a limited distribution. They became widely known after they received recognition at international exhibitions. Starting with an award at the 1879 Berlin Trade Exhibition, prizes followed in Brussels (1880), Melbourne (1881), Amsterdam (1883), Boston (1884), London (1884), Brussels (1889), Melbourne (1889), Munich (1890), London (1891), Vienna (1892) and Chicago (1893), Antwerp (1894) and Paris (1900). Leichner displays at many of these exhibitions were looked after by Fritz Leichner – possibly Jacob Rafael Friedrich Leichner – who began travelling the globe to promote Leichner face powders, greasepaints and make-up from around 1884.

Sales were also helped by the adoption of brighter electric stage lighting which began to replace gaslight from the 1880s. By 1900, Leichner stage make-up was being sold across Europe and Great Britain, North and South America, and even into Asia. The Prussian government was well aware of the value of Leichner exports and awarded Leichner the title of Kommerzienrat for his services to commerce in 1897.

Factory

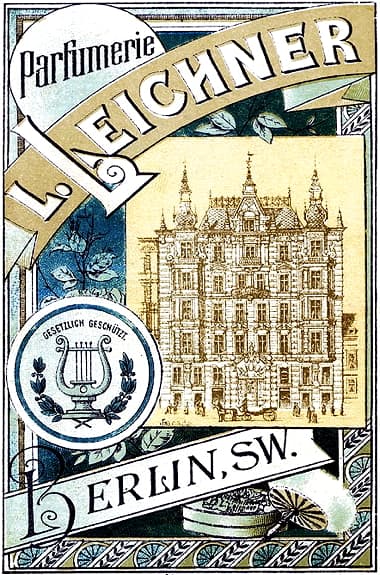

The building at Schützenstrasse 31 was destroyed during the Second World War but a Leichner brochure from the 1890s gives some indication of its size and proportions.

Above: Entrance to the Leichner factory at Schützenstrasse 31, Berlin.

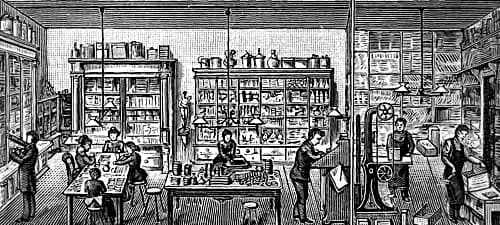

A series of lithographs published by the ‘Exposition Internationale Universelle de 1900’ may also provide some insight into its inner workings.

Above: L. Leichner factory. In the 1890s Leichner described the building at Schützenstrasse 31 as the largest establishment of its kind run by steam power. The man (right) is feeding coal into a boiler which is producing steam that is driving the motor rotating the shaft that runs across the top of the image which turns the mechanical mixer (left). Steam generated by the boiler is also used to heat the material being mixed by another man (centre). The two rectangular boxes to his left may be steam-heated water baths.

Above: L. Leichner factory. Women appear to be packaging materials into boxes and tins. The men (centre, right) look to be operating a printing press. Leichner produced a lot of its own packaging and publishing materials.

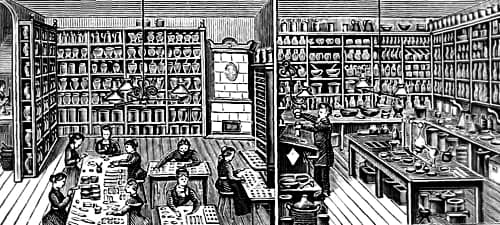

Above: L. Leichner factory. More women (left) packaging Leichner products which are then passed to boxed for shipping (right).

Above: L. Leichner factory. The women (left) may be wrapping individual items while the chemist (right) measures out ingredients.

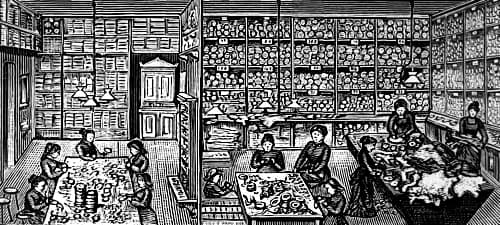

Above: L. Leichner factory. The women (right) are making powder puffs from what looks like sheep fleeces. These appear to be being added to powder boxes by the women (left).

Products

Leichner may have started out making greasepaints but, by the 1880s, he was also selling a wide range of products including perfumes, face and body powders, rouge, powder puffs, hair dyes, toothpastes, skin-creams and general ‘street’ make-up. Unfortunately, there are no detailed records of the all the products the company manufactured through to 1900.

Theatrical make-up

Traditional powder-based make-up used when stages were lit by candlelight had performance issues after brighter gas lighting was installed in theatres in the second half on the nineteenth century. To produce a more lifelike appearance, and improve the imperviousness of their make-up to the perspiration generated when working under the hotter gas lighting, a number of performers had been experimenting with greasy make-up by mixing powder with material such as tallow or cold cream. The make-up developed by Leichner was therefore not without antecedents.

See also: Greasepaint

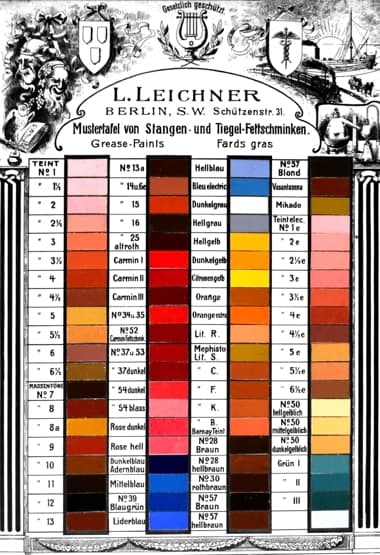

Leichner’s greasepaint was produced as round sticks, probably to make it easier to draw in the light and dark lines needed for old and character parts. The initial shade range was limited but there were nearly eighty colours available by 1903, some specifically developed for the new electric lighting; i.e. shades 1e - 6½e. To help artists apply his make-up, Leichner also produced albums showing how to use greasepaint to make-up a range of stock character types.

Above: 1903 Leichner-Album describing how to make-up 150 historical and theatrical figures.

Leichner promoted his greasepaints as lead free in response to a number of well-reported cases of performers dying after using make-up containing white or red lead. For example, the Belgian bass singer, Charles Zegler [1818-1864] had died from lead poisoning after lightening his moustache and beard with make-up containing white lead when playing Walter in ‘William Tell’ at Covent Garden, London.

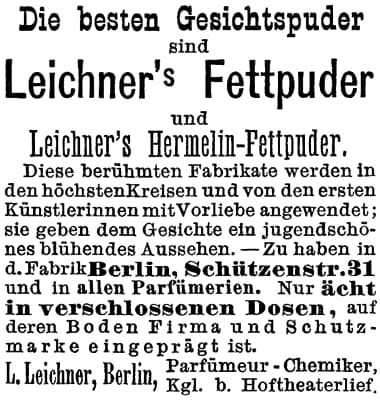

Leichner also manufactured a range of face powders for use on the stage. Some were used to set the greasepaint and reduce shine but others, such as Leichner Fettpuder, could be used on their own. Actresses of the time were reluctant to make themselves look older or to add lines when taking on a character part. This meant that while men generally adopted some form of greasepaint many actresses remained with powder. Fettpuder stuck to the face and resisted some of the effects of perspiration generated when working under the hotter gas lighting.

Ballet dancers and chorus girls also used body make-up and for them Leichner produced Eau de Lys, a type of wet white similar to versions made by other theatrical suppliers.

Also see: Liquid Face Powders

It seems likely that Leichner also made a wide range of theatrical ancillaries in the nineteenth century but apart from powder puffs, a range of rouges, and Nose Putty I have no hard evidence of their existence before 1900.

General cosmetics

A number of Leichner’s theatrical cosmetics soon found their way into general use, a process that was helped by widespread Leichner advertising.

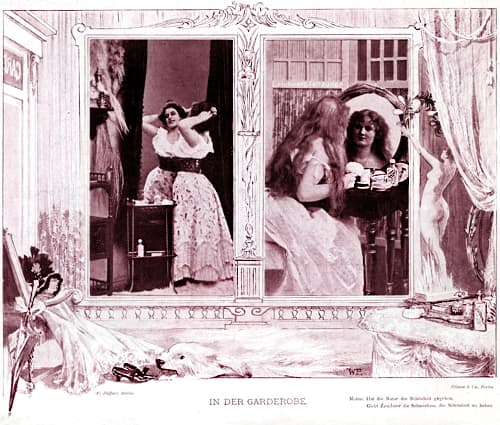

Above: 1898 Leichner In der garderobe (in the cloakroom), cosmetics for women.

Widely used Leichner skin creams included Patti Cold Cream, named after Adelina Patti [1843-1919], the Italian-French opera singer, allegedly made by Leichner specifically for her, and Glycerine Cream (Glycerincrême). Glycerine creams and cold creams were commonly used by women in the late nineteenth-century and similar items were made by a number of other cosmetic firms.

Also see: Cold Creams and Glycerine Creams and Jellies

Make-up items produced by Leichner through to 1900 included Fettpuder, the most widely known Leichner cosmetic from the nineteenth century, Hermelinpuder, Aspasiapuder, the previously mentioned Eau de Lys, and an assortment of rouges. Along with Leichner powder puffs and fragrances, some women may also have used Leichner crayons to make up their eyes.

Leichner and Wagner

By 1900, L. Leichner products were being sold around the world. Ludwig Leichner was now a very wealthy man and the lavish parties held at the Villa Leichner in Rheinbabenallee, Dahlem were well known.

Above: Villa Leichner at Rheinbabenallee 9, Dahlem.

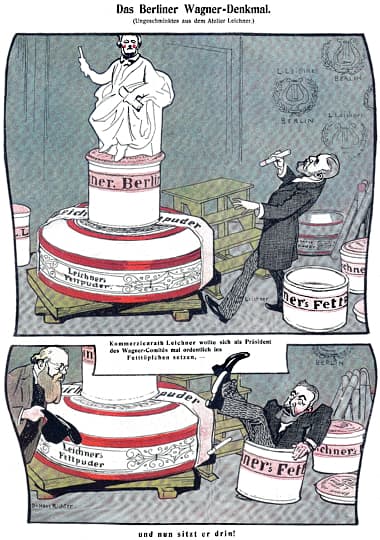

Leichner used his wealth to promote the work of Richard Wagner [1813-1883]. In 1895, Leichner money prevented a large collection of Wagner memorabilia from going to the United States. It is now housed at Eisenach in the former villa of the German author Fritz Reuter [1810-1874]. Leichner was also the major funder of a Wagner monument created by the sculptor Gustav Eberlein [1847-1926] that was unveiled in Berlin in 1903. Unfortunately, the project was opposed by Cosima Wagner [1837-1930] and Wagner’s descendants. None turned up for the ceremony and their opposition meant that only minor members of the German aristocracy attended and the associated festivities were scaled back. Leichner was also satirised in the German press over the issue.

Above: 1903 Unveiling ceremony of the Wagner monument in Berlin, Kommerzienrat Leichner (left), Prince Eitel Fritz [1883-1942] and Prince Friedrich Heinrich of Prussia [1880-1925] (saluting).

Generational change

In 1911, Ludwig Leichner celebrated his seventy-fifth birthday with a large party at the Villa Leichner.

Above: 1911 Festivities to celebrate the birthday of Ludwig Leichner.

He died the following year and the business passed into the hands of the next generation who would face challenges and introduce a series of changes.

Timeline

| 1873 | Factory established at Schützenstrasse 31, Berlin. |

| 1883 | New Products: Hermelinpuder. |

| 1896 | New Products: Aspasiapuder. |

Continued onto: Leichner (1910-1945)

First Posted: 30th September 2020

Last Update: 23rd June 2022

Sources

Berliner Leben: Zeitschrift für Schönheit und Kunst. (1911). Issue 14.

Eisenberg L. J. (1903). Ludwig Eisenberg’s grosses biographisches lexikon der deutschen bühne im XIX. Jahrhundert. Leipzig: Paul List.

Exposition internationale universelle de 1900. Monographies des grandes industries du monde. (Vol. annexe du catalogue général officiel). (1900). Paris: Imprimeries Lemercier; Lille: L. Danel.

Gellert, G. (1891). L. Leichner. Österreichische Musik- und Theaterzeitung. III(8), 1-2.

Hartnoll, P. (Ed.). (1967). The Oxford companion to the theatre (3rd ed.) London: Oxford University Press.

Hilmes, O. (2010). Cosima Wagner: The lady of Bayreuth. (S. Spencer, Trans.). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Paul, H. (1887). The art of making up. The Voice. X(11), 177-178.

Johann Ludwig Leichner [1836-1912].

1879 L. Leichner.

1886 L. Leichner face powders.

1887 Leichner stage paints and toilette powders.

1890 Leichner awards from international exhibitions.

Leichner building at Schützenstrasse 31, Berlin.

1891 Leichner Fett- and Ermine Powder (England).

1896 Leichner Fettpuder and Hermelinpuder.

1897 Leichner Fettpuder, Hermelinpuder and Aspasiapuder.

1898 Leichner Grease Paints available in London.

1899 Polvo Graseoso de Leichner (Fettpuder) (Argentina).

1899 Leichner Face Powders and Grease Paints (USA).

Banquet being held at the Villa Leichner painted by William Pape [1859-1920] circa 1899.

1903 Colour card for Leichner greasepaints. Each colour has been individually pasted onto the card.

1903 Cartoon lampooning Leichner’s efforts to erect a Wagner monument in Berlin.

Unveiling of the Richard Wagner Monument in the Tiergarten painted by Anton von Werner [1843-1915] in 1908.

1907 Sarah Bernhard (Bernhardt) [1844-1923], Paris, endorsement for Leichner.

Leichner Fettpuder.

An assortment of Leichner cosmetics.

1910 Leichner powder, make-up and cosmetics.

1911 Siegried Leichner [1889-1962] (top left) at his father’s birthday party at the Villa Leichner. It is perhaps noteworthy that of Leichner’s three sons, only Siegfried appears to have attended the celebrations.