Revlon

Continued to: Revlon (1945-1960)

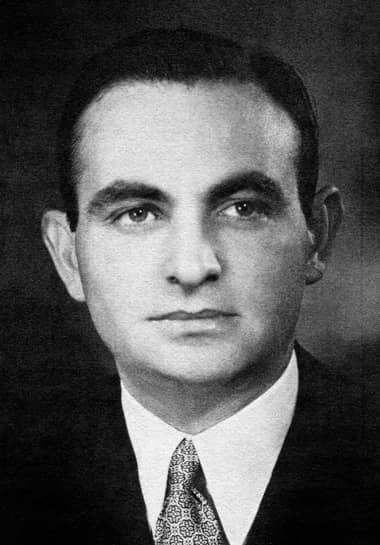

Starting in 1932, as a small nail polish business, Revlon would go on to become one of the largest cosmetics companies in the United States with a complete skin-care, hair-care and make-up range. Much of the credit for its success has been attributed to one of the company’s founders, Charles Revson.

Charles Revson

A lot has been written about Charles Revson, much of it very uncomplimentary.

Whatever else he was—nasty, crude, lonely, virile, brilliant, inarticulate, insecure, generous, honest, ruthless, complicated—Charles Revson was a man of single-minded persistence and drive, entirely dedicated to his business. And a perfectionist.

(Tobias, 1976, p. 31)

Complex. Shy. Private. Crude. Smart. One could go on and on with adjectives describing Revson. All would fit at one time or another. He was such a strange mix of persons and personalities that no generalization would have properly profiled.

(Abrams, 1977, p. 27)

Tobias and others give a potted history of Revson’s early life. They note that he was born in Somerville, Massachusetts in 1906, the son of Jeanette Weiss and Samuel Morris Revson, but grew up in Manchester, New Hampshire as the middle child between two brothers, the older Joseph and the younger Martin. After graduating from Manchester Central High School in 1923 he went to work in the garment district of New York as a salesman for the Pickwick Dress Company where he worked his way up to becoming a piece-goods buyer. In 1930, he ran away to Chicago with Ida Thompson to get married but soon returned to New York, got divorced and moved back in with his parents. In 1930 or 1931, he started selling nail polish for the Elka company founded in 1928. However, after working there for a short time, he resigned and established what would become Revlon with his older brother, Joseph Revson, and a business acquaintance, Charles Lachman.

Revlon Nail Enamel Corporation

The new company to be named Revlac – an amalgamation of Revson and Lachman – but it did not sound right (Tobias, 1976, p. 30) so an ‘L’ replaced the ‘S’ in Revson and Revlon started up at 38 West 21st Street, New York in March, 1932. The company incorporated the following year as the Revlon Nail Enamel Corporation with Charles Revson as president, Joseph Revson its treasurer and general manager, and Charles Lachman its vice-president and technical adviser. The youngest Revson brother, Martin Revson, would join the firm in 1935 and become its marketing manager.

Above: 1951 Charles Revson (president), Charles Lachman (vice-president) [1897-1978], Martin Revson (vice-president) and Joseph Revson (treasurer and general manager).

It is sometimes said that Charles Revson took a big risk leaving a paid job at Elka to start out on his own in the middle of the Great Depression but the risk may not have been as large as it first appears. From all reports Elka was a very small firm and Revson was probably getting most of his income from commissions, so going out on his own and selling for himself was potentially a move up.

The biggest risk Revson faced in his new venture was a guaranteed supply of nail polish. This explains why Charles Lachman was so important to the business and why was he given a half-share in the company: the family of Lachman’s wife, Ruth Young [1892-1949], owned the Dresden Chemical Company. They made nail polish – possibly even for Elka – and Lachman’s involvement was on the condition that Dresden would supply Revlon with nail polish on credit.

Also, nail polishes do not appear to have suffered the slump in sales experienced by other cosmetics during the 1930s. In a piece of self-promotion, the J. Walter Thompson Company – the advertising agent for Cutex – noted that manicure sales had actually risen between 1929 and 1932.

In the three depression years since 1929, total dollar sales volume for Cutex manicure products has been 28% greater than in the three preceding years — following a steady sales growth since 1915.

(J. Walter Thompson Company advertisement, 1933)

As a salesman, Revson’s main problem was how to outdo the competition. The largest nail polish company of the time was Northam Warren, who held the Cutex, Glazo and Peggy Sage brands, but there was also Blue Bird, La Cross, and later Chen Yu, and Dura Gloss, amongst others. Revlon not only survived, it prospered. In its first ten months of business it only did US$4,055.09 in sales but this jumped to US$11,246.98 in 1933 reaching US$1.2 million by 1940 (Tedlow, 2003). This is not to say that the early years were easy and Joseph Revson can take much of the credit for guiding the early company financially through this time.

Nail polish

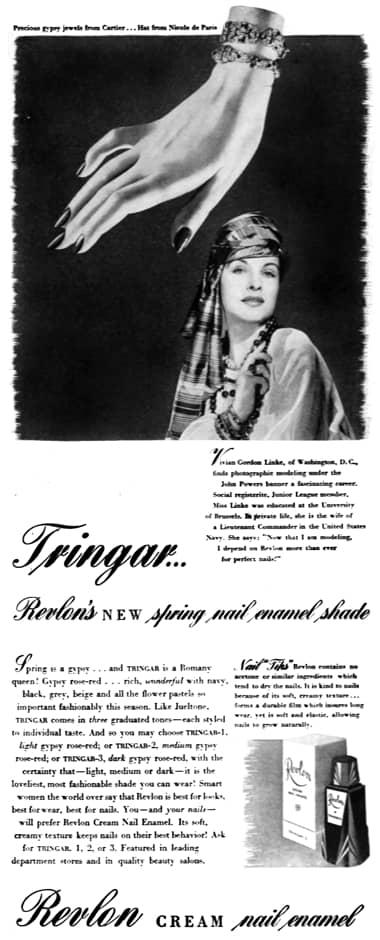

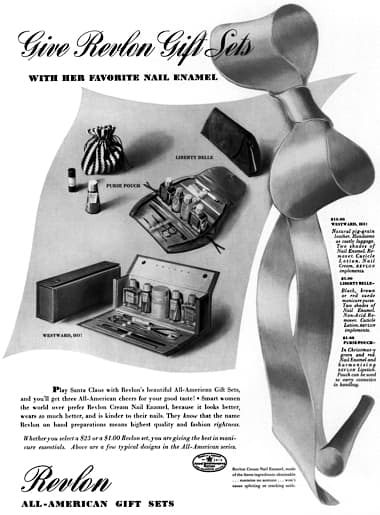

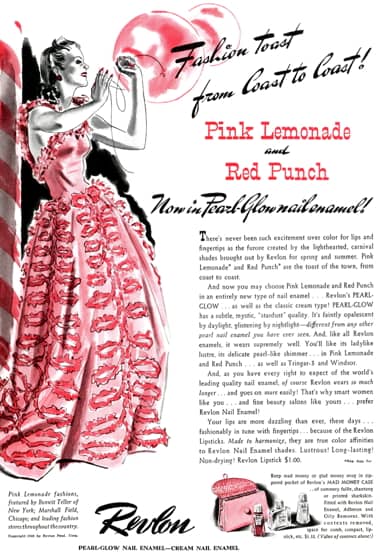

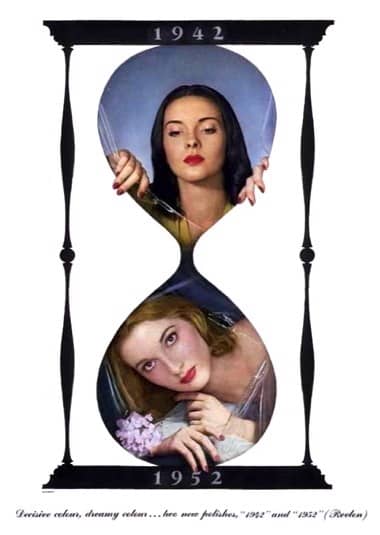

As its name suggest Revlon started with a single product, an opaque/cream nail polish. The initial colours in Revlon‘s 1932 range are unknown to me but shades introduced up to America’s entry into the Second World War included: Sun Rose, Chestnut, Cubana, and Riviera (1935); Ascot, Savoy, and Windsor (1936); Newport, Nassau, Suez, and Sierra (1937); Cricket, Aurora, Lancer, Tartar, and Juelton 1, 2 & 3 (1938); Bravo, Chilibean, Shy, Red Dice, Tringar 1, 2 & 3, Pink Cloud, and Amoa Red (1939); Pink Garter, Scarlet Slipper, Pearl Glo, Pink Lemonade, Black Mask, Raven Red, Demitone, and Red Punch (1940); and Cherry Coke, Hot Dog, Rosy Future, Hothouse Rose, 1942, 1943, and 1952 (1941). 1941 also saw the introduction of Pearl Glow, a luminous nail enamel in Red Punch, Scarlet Slipper, Tringar 3, and Windsor shades, with Pink Lemonade, Suez, and Pink Garter shades of Pearl Glow added later in the year.

One reason often given for Revlon’s success is that its nail polish was superior to other brands. According to this story Charles Revson had realised the potential of the Elka’s opaque nail polish and made it better by producing it in a wider range of shades.

Elka’s product, however, was revolutionary. It was opaque. All the other nail polishes on the market were transparent. Charles saw the potential in this difference. The others were made with dyes and were limited to three shades of red—light, medium, and dark. Revson felt that polish—“cream enamel,” as it came to be called—made with pigment so that it would really cover the nails, and made in a wide variety of shades, could capture the market.

(Tobias, 1976, p. 49)

Although overstated there is some truth to this story. Most nail polishes at that time in the United States were formulated to be transparent and used dyes rather than pigments as colourants. In the early 1930s the fashion trend was to only colour the nail across the centre of the nail plate, leaving the moon and the free edge clear. When applied with skill this look went well with transparent nail polishes. Cutex was still promoting this nail fashion as late as 1938, even though it had introduced a cream polish in 1934.

By contrast, opaque or cream nail polishes – containing pigments including titanium dioxide – were usually painted over most or the whole fingernail. They hid flaws in the nail and were easier to apply.

What is not true is that transparent polish only came in a limited range of colours – Peggy Sage, for example, had a dozen or so different shades of nail polish in 1930 that could be harmonised with jewellery. It is also not correct to say that Elka was the only company making cream polishes. Again, Peggy Sage, for example had some in her range.

See also: Peggy Sage

However, the number of shades was not as important as the colours in the range. The exuberant 1920s had ended with nail polish being produced in a wide variety of colours – including blues and greens as well as metallic colours like gold, silver, and bronze – but the depression years of the 1930s would see nail fashions move to more subdued reds and smokey-reds and this was the colour range Revlon was promoting.

Back in 1933, cream nail enamel was received by beauty salon and consumer alike with great enthusiasm, for it gave the nails a covering that hid flaws as no product had ever done before. And it gave Revlon the “hook” by which they could enter the style business with a commodity.

With cream nail enamel, a range of reds could be developed that would not only flatter the hands, but would also harmonize with the clothes a woman wore. Crazy colors were soon dismissed as being unwearable and in bad taste, colors such as chrome-yellows, weird blues and greens, fantastic shades that were the first obvious ones to think of, aside from reds. However, subtle, smokey tones, in the spectrum or red ranging from light to dark, beautified a woman’s nails and hands, and, at the same time, could be made to harmonize with her wardrobe.(Rise of Revlon, 1947, p. 481)

This was not the only reason why reds came to dominate nail polish colours in the 1930s. The growing trend to match nail polish with lipsticks also saw a turn to reds.

Above: 1937 Revlon Nail Enamel Corporation showrooms at 125 West 45th Street, New York.

The colours selected for Revlon Nail Enamels were mostly the work of Charles Revson. Whatever else that might be said of him, he did have a good eye for colour, at least as it applied to make-up and clothing; furnishings and fixtures were another matter. More importantly, Revson treated nail enamel colours like fashion items and, from 1937, brought out new shades each spring and autumn. All of Revlon’s marketing efforts would then be put into promoting the new shades while older ones, if still available, were soft-pedalled. Revson’s commitment to this idea was such that, in 1937, he opened a style department at Revlon – run by Miss Cherie Shackleton – specifically to promote style and fashion in manicure items.

Above: Scarlet Slipper (1940), Cherry Coke (1941) and Chilibean (1939).

As well as colour, Revlon nail enamels may have been superior in other ways, as the story below – repeated in books about Diane Vreeland – suggests:

Mrs Vreeland – later fashion editor of Harper’s Bazaar and subsequent editor of Vogue – became close to a friend of Flame’s [‘Flame’ d’Erlanger], simply called Perrera, who dabble in investments, but whose greatest love was giving manicures. … Perrera’s polish was made to a special formula which he alone knew, drying almost instantly to a rock-hard finish. From time to time he would give some to friends, and when Mrs Vreeland returned to New York in the late 1930s, she took two bottles with her.

The polish so impressed Mrs Vreeland’s manicurist that she offered to have a boyfriend take a look at it. ‘I think I can get him to copy it,’ said the manicurist. ‘Really,’ replied la Vreeland. ‘Who’s the boyfriend?’ ‘Charles Revson,’ came the reply. The Revlon range by this time had a great colour palette and a reputation for not chipping but, as Mrs Vreeland recollected, ‘it took hours to dry and had no staying power’. She remained convinced that ‘Revson studied Perrera’s formula and evolved a product that dried faster than anything anyone had ever used in America’.(Woodhead, 2003, pp. 210-211)

There are other reports that Revlon had a quality product. A. C. Bailey, of the Bailey Beauty Supply Company, Chicago – who admittedly became a Revlon distributer in 1934 and may therefore be a little biased – is quoted as saying:

“I went with him,” Bailey says, “because I had checked with some of the finest beauty shops in the east, like Michael of the Waldorf, and found the polish was incredible. It was chip-proof and had more stay-on power, had more gloss and lustre, the colors were beautiful, and the formula was just terrific. We were carrying at the time about five brands of nail polish. Blue Bird, Chen-Yu, Glazo and a couple of others. We threw everything else out and carried only Revlon.”

(Tobias, 1976, p. 65)

Revlon nail enamels therefore appear to have been as good as, if not better than its competitors. In part, this was due to Revson’s obsession with quality. Quality concerns may have been the reason for Revson switching his nail polish supplier from Dresden to Maas & Walstein around 1937, although a cynic might interpret this move as an example of Revson’s aversion to being beholden to anyone, and/or part of the move that saw Lachman’s share of the Revlon business cut from one-half to one-third (Tobias, 1976, p. 51).

Sales force

Even if we accept that Revlon’s nail enamel was good and its colours fashionable I do not think this completely explains the rise in the company’s fortunes in the 1930s. For that we need to look at Revlon’s sales force.

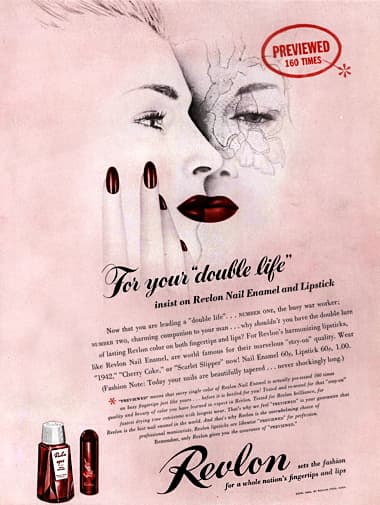

Charles Revson was a very successful salesman. He was enthusiastic, quite good looking when younger, would endear himself to female buyers by arriving with his nails painted in the latest Revlon shades, and was apparently prepared to exchange sex for a Revlon sale or extra counter space if the opportunity arose.

When Martin Revson joined Revlon in 1935 as its sales manager, he proved to be an even better salesman and was very effective in building Revlon’s sales team. In a 1951 interview, he outlined three types of sales practices – canned, franchise and executive – with ‘executive’ being the highest class and the one Revlon used.

Sales chief Martin Revson believes there are three kinds of selling. First is what he calls the canned talk type. Salesmen using this type usually sell nuts or bolts or cigarettes—some product for which there is a constant demand and which will sell pretty much according to the number of calls made per day. The formula is: The more accounts you visit, the more you sell.

The second type of selling, as labeled by Martin Revson, is the franchise type. Some companies have franchised one dealer per town or one dealer per neighborhood in large towns. The company representative calls on these dealers, looks over their stock and practically writes the order for them. Mr. Martin, as he is called at Revlon to distinguish him from his brothers, thinks that opportunities for constructive selling under the franchise system are limited.

The third and highest class of selling—the one Revlon uses—is described as the executive type of selling. In Revlon’s case, the salesman is an advertising specialist, a display specialist, a stock specialist and an expert in the use of make-up.

Now, salesmen of this kind aren’t born—they’re trained.(Dallaire, 1951. p. 117)

However, ‘executive selling’ was supplemented by a number of very aggressive sales practices.

Revlon salesmen were expected to win. If a Chen-Yu nail enamel color chart somehow walked out of a store in a salesman’s briefcase … well, it could always be replaced by a Revlon color chart. If the bottle caps on some Chen-Yu nail enamels were loosened a bit and the enamel hardened … well, the store, or the customer, would know not to buy an inferior brand again. If, in an attempt to secure counter space, a salesman should spread his arms out, accidentally sweeping the competitive product off either end of the counter onto the floor … well, the salesmen were authorized to buy up the damaged merchandise at the retailer’s cost and replace it with Revlon product.

(Tobias, 1976, p. 68)

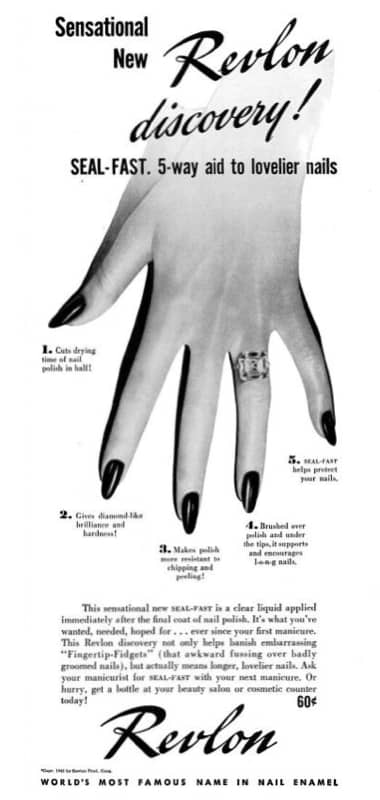

In its endeavours to ‘bury the opposition’ Revlon continued to use these dubious sales practices and added others. Leaving aside charges of wire-tapping in the 1950s – strongly suggested but unproven – the most important of these was coercion. Revlon was not above using a bit of ‘muscle’. In 1942, for example, a trade magazine reported that the Los Angeles company, Seal-Cote Co., had accused Revlon of violating its trade-name and pressuring dealers. Seal-Cote made the charge that not only was Revlon’s Seal-Fast an imitation of their product Seal-Cote, but that since Revlon had introduced their product in 1941, the company had been “coercing dealers, jobbers and beauty parlours not to carry Seal-Cote“ (AP&EOR, 1942) resulting in the cancellation of numerous Seal-Cote orders.

This was not an isolated case and eventually the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued Revlon with a series of cease and desist orders in 1954 and 1956. However, by then it was too late. After 1955, demand for Revlon products was such that that coercion was largely unnecessary.

Revlon’s attempts to shut out competitors date back more than 20 years and it took the Trade Commission some time to get this giant specialist on women’s beauty to agree that it would quit using unfair trade practices on those beauty shops which dared sell a rival product.

Here is some of the sworn testimony showing how Revlon tried to dominate the lipstick market.

The Royal Supply Co., a Houston, Texas, beauty Jobber, wrote Thomas Products of Buffalo, a nail cream manufacturer, 4/1/46: “Please do not ship your order of 3/13/46. Since we handle Revlon, they do not want us to handle competitive items.”

Here is another letter from Revlon to O. L. Becker of the B-G Supply Co., Albuquerque: “It is understood that in consideration for granting you the distributorship for Albuquerque you will of course carry Revlon preparations only and accordingly promptly dispose of any stock you may have on hand of other preparations.”

Again, Mortimer A. Fogel, manager of quality cosmetics of New York, testified, 12/1/49, that the Duchess Beauty and Barber Supply of Knoxville, Tenn., had returned to him an entire year’s supply of “Monique” beauty products, excluding 40 gallons of shampoo, after signing with Revlon.(The Chillicothe Constitution-Tribune, Missouri, 17 Feb. 1960, p. 14)

Above: 1941 Revlon sales meeting.

As it became a larger cosmetic company, with a strong department store presence, Revlon improved its sales by placing demonstrators in select stores and made payments of ‘push money’ elsewhere. By 1955, the company had over 600 demonstrators employed in department stores throughout the country. As well as promoting Revlon products, the demonstrators could give immediate feedback by telephone on how lines were moving (Television Magazine, 1955); feedback that was added to field reports from regional managers, salon and department store representatives.

Salons

Revlon’s sales in the 1930s were helped by its early business being salon-oriented. The popularity of the new permanent waves attracted a lot of customers to American beauty salons in the 1930s and many women would have a manicure while waiting for their hair to set. It was a lot easier for a Revlon salesman to get an order from a salon than a department store, and a salon manicure allowed customers to try and then buy a Revlon nail enamel. Salons that tried the product and liked it would reorder and their customers would spread the word. Revlon’s growing popularity in salons also helped Revlon salesmen convince department stores that they need to stock Revlon products.

Revlon began selling to department stores in 1935, but continued to produce products that were aimed at making salon manicures a total Revlon experience. The company provided salons with information on how to sell manicures and gave suggestions on different manicure treatments.

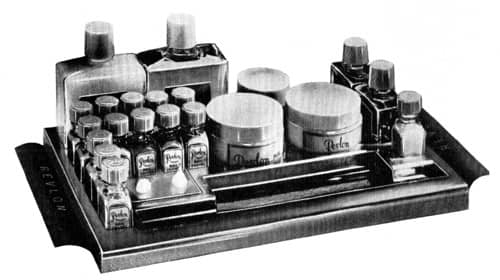

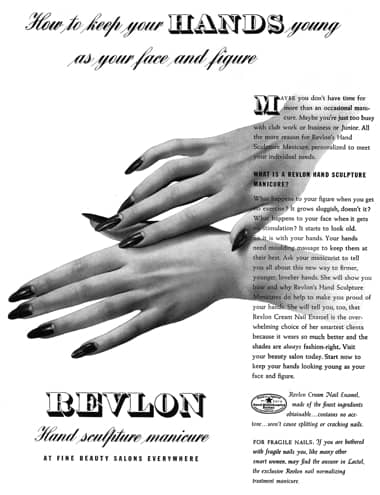

Special, personalized manicures have been developed by Revlon and outlined in a booklet, “How to give … how to sell Revlon Manicures.” Just as the hair requires individual treatment in permanent waving so to do different hands, Revlon maintains, and suggests four techniques: a style manicure; a lactol manicure for dry, brittle hands; a hand sculpture manicure with massage; a hand sculpture manicure with arm massage. Each incorporates one or more of four new Revlon products. They are hand massage cream for lubrication, a hand finishing lotion, a hand cream of the pink pearly type and an emulsified pearl hand lotion. These items, in addition to some new steel implements and nail enamels, are offered in a handsome chrome manicure tray.

(AP&EOR, 1939)

These treatments used a range of Revlon cosmetics introduced in the 1930s including: Adheron, a base coat (1933); Oily Polish Remover (1935); Prolon for weak, brittle nails, and Lactol (1938); Cuticle Lotion; and Nail Cream along with other manicure equipment like emery boards and orange sticks. Then, in 1939, Revlon added a range of hand lotions.

Above: 1939 Revlon manicure tray containing massage cream, hand creams, nail enamels, remover and manicure implements.

By 1941 Revlon manicure cosmetics included:

Adheron: “Base coat which tends to smooth out irregularities of nail surface and provides smooth foundation for enamel. Prolongs wear.”

Prolon: “[F]or nails inclined to split, flake or break.”

Nail Cream: “[H]elps keep nails strong and cuticle soft and smooth.”

Oily Polish Remover: “Gentle remover with an oil content that tends to lubricate dry nails and cuticle.”

Cuticle Remover: “Tends to remove cuticle gently, without leaving it harsh or dry.”

Cuticle Oil: “A lubricant for softening and smoothing harsh cuticle.”

Solvent: “For restoring thickened nail enamel to its original consistency.”

Nail Fix: “First aid for a broken nail.”

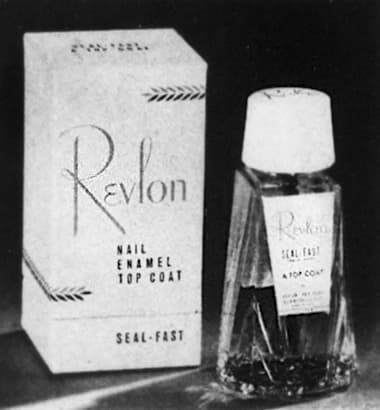

Seal-Fast: “[D]urable and resilient, resists ordinary knocks, gives good protection for nail enamel.”

Pearl Hand Cream: “Light, delicately scented. Leaves hands soft but not sticky.”

Pearl Hand Lotion: “For those who prefer lotion to cream.”

Night Cream: “A rich lubricating type of cream that tends to make fine lines less noticeable . . . smoothes away roughness; leaves hands soft and pleasant.”

Hand Finishing Lotion: “Clear liquid that helps soften hands and combat excess perspiration.”

Revlon Implements: “A complete line of American-made files, nippers, scissors, etc., as fine as can be made.”

Above: 1942 Revlon manicurist.

Northam Warren

Another factor that helped Revlon grow was the action of its biggest competitor, Northam Warren, the owners of the Cutex, Glazo and Peggy Sage nail polish brands. Collectively, these brands controlled most of the nail polish business in the United States by the 1930s but its dominant position may have worked against it.

As Revlon entered the retail market, a number of forces were operating to make a new competitor and a change in status very welcome to a major part of the retail trade. Certain deep antagonisms existed in the mind of the retail trade and certain basic dissatisfactions with the policy of a predominant supplier. Throughout the retail trade there was an eager expectation for someone vigorous, with a new idea that could be picked up, accepted and promoted as a foil to this other company. Revlon stepped into this fortunate retail situation at the precise psychological moment with a new product and a new sales idea. The result is history in this industry.

(Nail enamel, 1958, p. 458)

Even if this ‘industry antagonism’ was not as severe as this author makes out, it is clear that Northam Warren failed to fully capitalise on their introduction of cream nail polish or the harmonising of nail polish with lipstick, ideas it had introduced before Revlon.

See also: Nail Polish and Cutex

Lipstick

The idea of matching nail enamels with lipsticks dated from the late 1920s. Cutex had already introduced a line of lipsticks to match its Crème Nail Polish range which was first sold in 1934. Debuting in 1935, Cutex lipsticks came in automatic containers in four shades: Natural, Coral, Cardinal and Ruby, with advertisements that used headlines such as “Fashion says—Lips and fingertips now must match”.

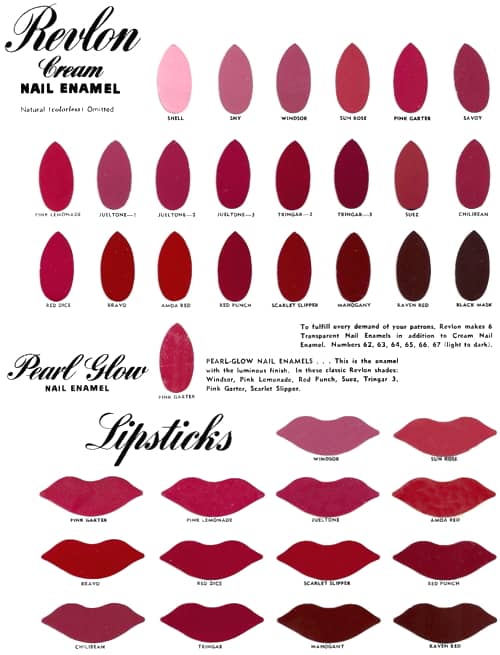

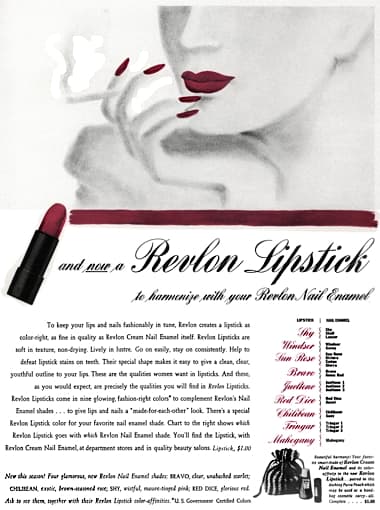

Five years later, in 1939, Revlon introduced its own lipsticks in nine shades with colours matched to Revlon nail enamels.

Above: 1939 Revlon lipstick shades coordinated with nail enamels.

Revlon salesgirls were supplied with charts which they could use to advise customers on which shade went with which.

Above: 1940 Revlon shade chart for Cream and Pearl Glow Nail Enamels, and Lipsticks.

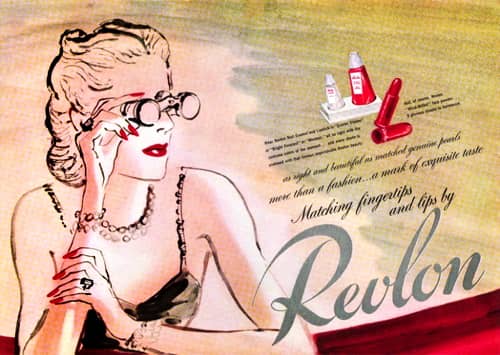

Revlon supported sales with an advertising campaign that used coloured advertisements – a first for Revlon.

Above: 1940 Revlon Fashions in Lips, Fashions in Fingertips.

Some of these used the slogan ‘Matching fingertips and lips’, a reversal of the tag used by Cutex.

Above: 1944 Matching Fingertips and Lips by Revlon.

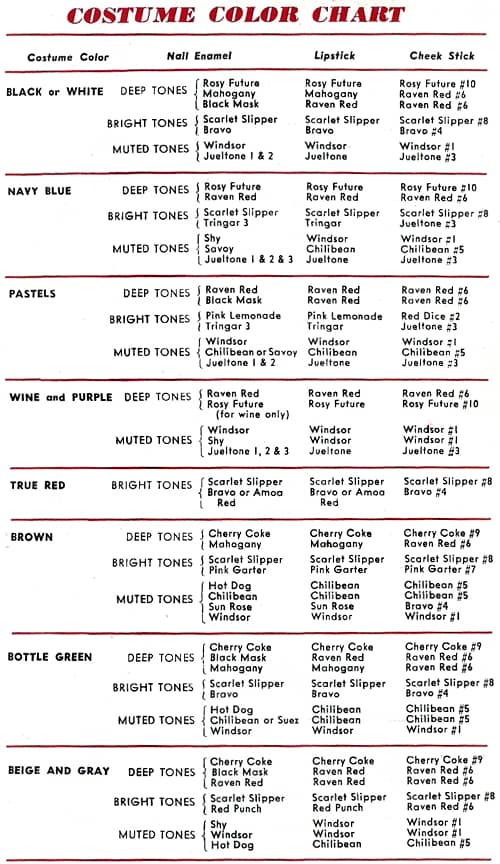

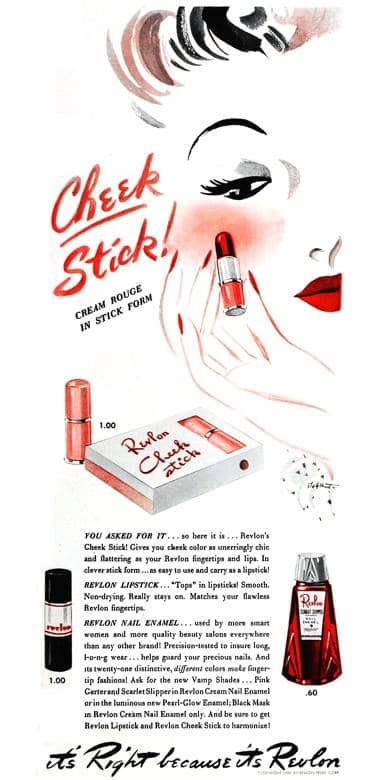

As it was no longer just in nails, Revlon changed its name to the Revlon Products Corporation and followed up the introduction of lipstick with Cheek Stick (1940), a cream rouge in stick form – that came with a small packet of tissues to help spread the rouge without staining the fingers. The following year Revlon added a lipstick brush.

Above: Revlon Cheek Stick.

Cheek Stick: “Cream rouge in clever stick form so that you can apply your cream rouge directly to your skin.” Shades: Windsor, Red Dice, Rosy Future, Raven Red, Scarlet Slipper, Bravo, Jueltone, Chilibean, and Cherry Coke.

Above: 1941 Revlon Nail Enamel, Lipstick and Cheek Stick colour coordinated with fashion colours.

Also see the booklet: Fashions in Hands (1941)

Copying what Cutex did by matching lipstick with nail polish would not be the last time Revson capitalised on an idea developed by others. Charles Revson was not a creative product genius and a lot of what Revlon produced was copied from competing cosmetic companies. When others came up with a good product Revson would have it analysed, improve the formulation where possible and conduct an extensive advertising campaign to help sell it. As Mike Sager, a Revlon salesman noted:

“Copy everything and you can’t go wrong,” he remembers Charles telling him. That way—and it was basically Charles’s formula for forty-three years—you let the competitors do the groundwork and make the mistakes. And when they hit with something good, you make it better, package it better, advertise it better, and bury them.

(Tobias, 1976, p. 63)

Although this is an oversimplification – copying was endemic to the cosmetics industry as a whole – it contains more than a grain of truth. There are more examples of Revlon copying its rivals than the other way around.

He [Revson] gave many hours of his time each week to the laboratory. As he often told me, “That’s where it starts,” adding, “If it’s wrong there, kiddie, forget it!” He was not a chemist but learned quickly what the technological side of chemistry could do for his business. He filled his laboratory with every conceivable electronic device capable of producing and measuring products. He once said to me, during a competitive discussion, “Anything they make, we can break down in twenty four hours and copy.” He did, too.

(Abrams, 1977 pp. 244-245)

Global expansion

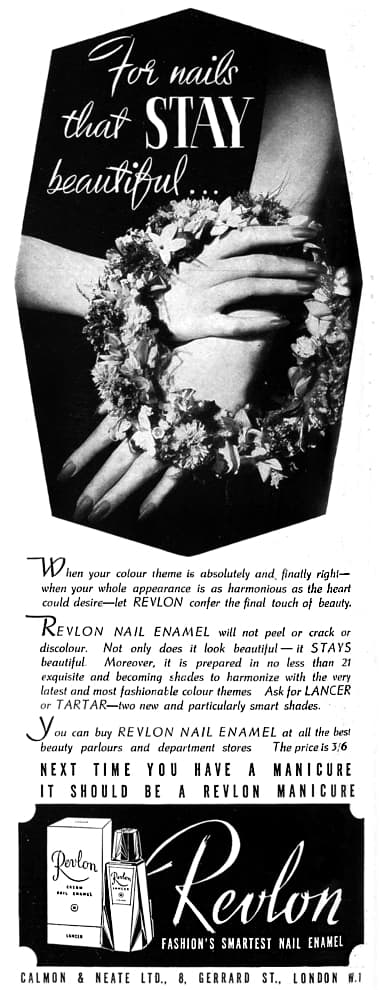

In 1938, Revlon established the Revlon Export Corporation and began distributing its products in other countries. The company may have been selling its products into Canada earlier than 1938 but by the time the Second World War broke out, Revlon products were also available in Britain – distributed by Calmon & Neate – and parts of Latin America. Further expansion would have to wait until after the war.

Wartime

The United States entered into the Second World War late in 1941. Revlon contributed to America’s war effort, by assembling first-aid kits, making dye markers for the navy, and even manufacturing hand-grenades for the army. Charles also lost Martin Revson for the duration of the war when his brother joined the navy.

1943 Revlon Victory Crate containing a Nail Enamel, Oily Polish Remover, Adheron and other manicure accessories.

The war created supply shortages in glass, metal and assorted cosmetic ingredients and may have been the reason why Revlon rationalised its lines in 1943, dropping seven shades of nail enamel and matching lipsticks and suspending three shades of Cheek Stick. This still left seventeen shades of nail enamel remaining and the war shortages did not stop Revlon from introducing new colours including: Mrs. Miniver Rose (1942); Bright Forecast (1943); Pink Garter, Pink Lightening, and Tournament of Roses (1944); and Russian Sable, and Dynamite (1945).

The most famous of these was Mrs. Miniver Rose with the lipstick packaged in a plastic case, as metal was in short supply. Revlon produced the shade without consulting M.G.M., the makers of the wartime propaganda film ‘Mrs. Miniver’ released in June, 1942 starring Greer Garson [1904-1996] and Walter Pidgeon [1897-1984]. Revson must have been gratified to see print fabrics, real and artificial roses and other fashion accessories on display in stores all over America soon after Revlon released the shade.

1942 Mrs. Miniver Rose window at Marshall Field and Company.

Despite the war shortages, Revlon also managed to introduce some new products, including a brief foray into leg make-up with Leg Silk and, more importantly, the addition of face powder into its range with Revlon Wind-Milled Face Powder (1943), perhaps made with a technology similar to that used to make Coty’s Air Spun Face Powder, introduced in 1934.

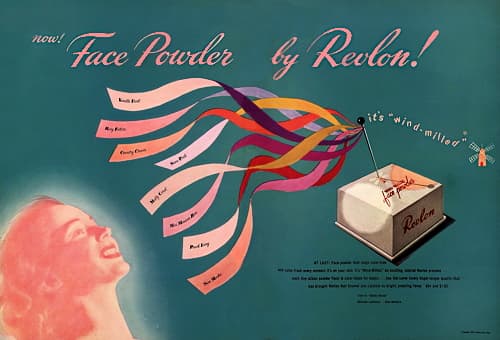

1943 Revlon Wind-Milled Face Power.

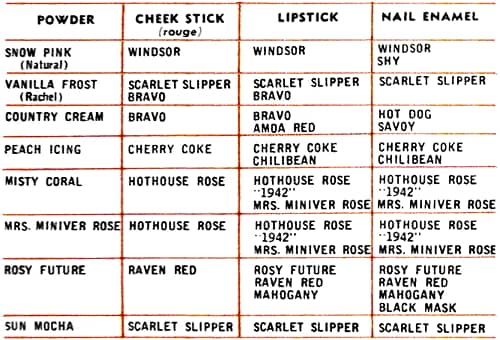

Wind-Milled Face Powder: “Revlon Face Powder is ‘wind-milled’, a special Revlon process in powder blending. Color and powder are fused together by wind to incredible fineness in great glass arcs until the color actually becomes an inseparable part of the powder itself!” Shades: Snow Pink, Vanilla Frost, Misty Coral, Peach Icing, Country Cream, Mrs. Miniver Rose, Rosy Future, and Sun Mocha.

Above: 1943 Revlon Face Powder color coordinated with Cheek Stick, Lipstick and Nail Enamel.

See also: Coty “Air Spun” Powder

Revlon continued to use full-colour magazine advertisements, first started in 1938 before beginning full-color, photographic advertisements in 1944.

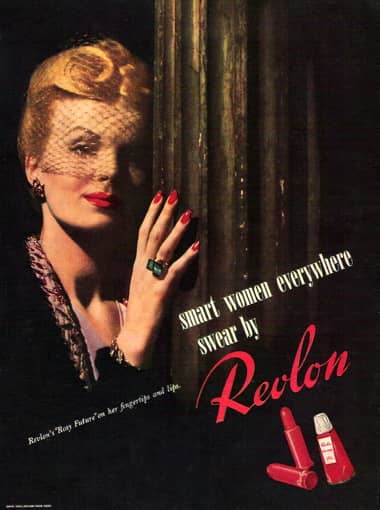

Above: 1943 Smart women everywhere swear by Revlon.

Revlon also made the winning bid of US$301,125 for the German firm Graef & Schmidt, Inc., New York which had been seized by the U.S. government in 1943 because of its German business ties. Revlon then exercised its option to buy the Graef & Schmidt’s factory buildings which allowed it to make its own manicure and pedicure implements.

Timeline

| 1932 | Charles Revson, Joseph Revson and Charles R. Lachman establish Revlon. New Products: Revlon Nail Polish. |

| 1933 | Revlon Nail Enamel Corporation established. New Products: Adheron. |

| 1934 | Revlon makes its first large sale to the Marshall Field department store. |

| 1935 | Martin Revson joins Revlon. New Products: Oily Polish Remover. |

| 1936 | Revlon opens a store account with Saks Fifth Avenue. |

| 1937 | New showroom opens at 125 West 45th Street, New York. Revlon Style Department opens. |

| 1938 | Revlon Export Corporation organised. Revlon established in Canada. New Products: Solvent; and Prolon. |

| 1939 | Revlon Nail Enamel Corporation changes its name to Revlon Products Corporation. New Products: Lipstick. |

| 1940 | New Products: Nail Fix; Pearl Hand Cream; and Cheek Stick. |

| 1941 | New Products: Seal-Fast; and Revlon Lipstick Brush. |

| 1942 | New Products: Nippit, cuticle nippers. |

| 1943 | Executive and sales staff moved to 745 Fifth Avenue, New York. Revlon begins radio advertising. New Products: Wind-Milled Face Powder; and Leg Silk leg make-up. |

| 1944 | New showrooms at 745 Fifth Avenue opened. New offices and showrooms opened in Los Angeles. |

| 1945 | Revlon acquires Graef & Schmidt, Inc., New York in a government auction. |

Continued onto: Revlon (1945-1960)

First Posted: 10th January 2012

Last Update: 26th April 2021

Sources

Abrams, G. J. (1977). That man: The story of Charles Revson. New York: Manor Books, Inc.

Broadcasting Telecasting. (1958). Washington, DC: Broadcasting Publications, Inc.

Dallaire, V. J. (1951). From an idea to $20,000,000 The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review, February, 115-118.

Nail enamel. (1959). Drug and Cosmetic Industry, 84(4), 458-459.

Revlon. (1941). Fashion in hands [Booklet]. U.S.A: Author.

Rise of Revlon. (1947). The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review, May, 481-482.

Tedlow, R. S. (2003). Giants of enterprise. Seven business innovators and the empires they built. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.

Tobias, A. (1976). Fire and Ice: The story of Charles Revson—the man who built the Revlon empire. New York: William Morrow.

Woodhead, L. (2003). War paint: Miss Elizabeth Arden and Madame Helena Rubinstein. Their lives, their times, their rivalry. London: Virago.

Hyman Charles Revson [1906-1975] a.k.a Charles Haskell Revson. Exactly how the name change took place is a mystery but it is possible that as Revson’s son was called Charles Haskell Revson Jr. [b.1946] everyone assumed this was the name of his father.

Revson Family. Samuel Morris Revson [c.1874-1949] and his wife Nettie Leah (Janette) Revson, nee Weiss, [1884-1933] with their three children from left to right: Hyman Charles Revson, Joseph Revson [1905-1971] and Martin Elliot Revson [1910-2016].

1935 Revlon Nail polish. Revlon’s first advertisement in ‘The New Yorker’, August 10.

1936 Revlon Nail Polish. Charles Revson would later insist on using the word ‘enamel’ instead of ‘polish’ as he thought it sounded ‘classier’.

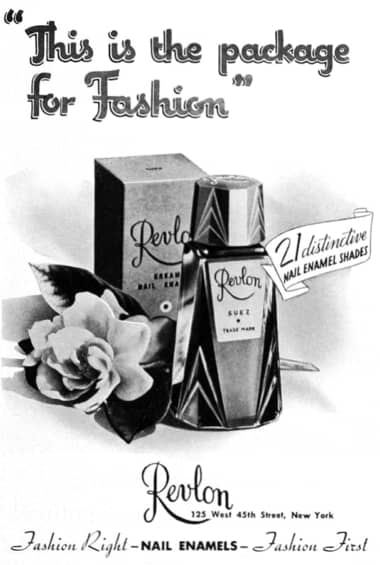

1937 Revlon Nail Polish in 21 shades.

1938 Revlon Nail Enamels in a bottle shape the company would use through to 1947.

1938 Revlon Prolon, a nail base.

1938 Revlon Nail Enamel in Tartar, Lancer, Suez and Sierra shades. The company is now established in Canada at 151 Sparks Street, Ottowa.

1938 Revlon Jueltone.

1938 Revlon Nail Enamel (Britain).

1939 Revlon Hand Sculpture Manicure. One of a range of manicures Revlon suggested.

1939 Bravo, Chilibean, Shy and Red Dice Nail Enamel.

1939 Revlon Lipsticks.

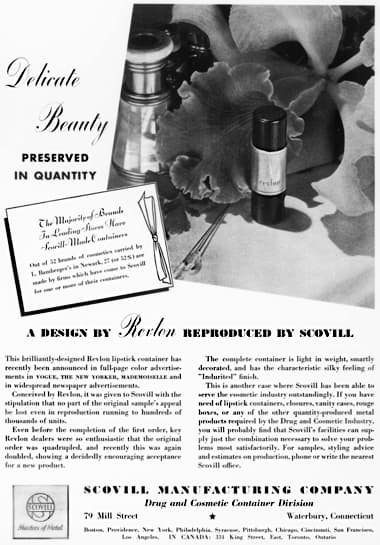

1939 Revlon Lipstick container made by Scovill. It was replaced with a bullet-stye case by 1941.

1939 Revlon Nail Enamel in Tringar – light, medium and dark – shades.

1939 Revlon Gift Sets.

1940 Revlon Cheek Stick.

1940 Revlon Pearl-Glow Nail Enamel, a pearlescent nail polish, in Pink Lemonade and Red Punch shades.

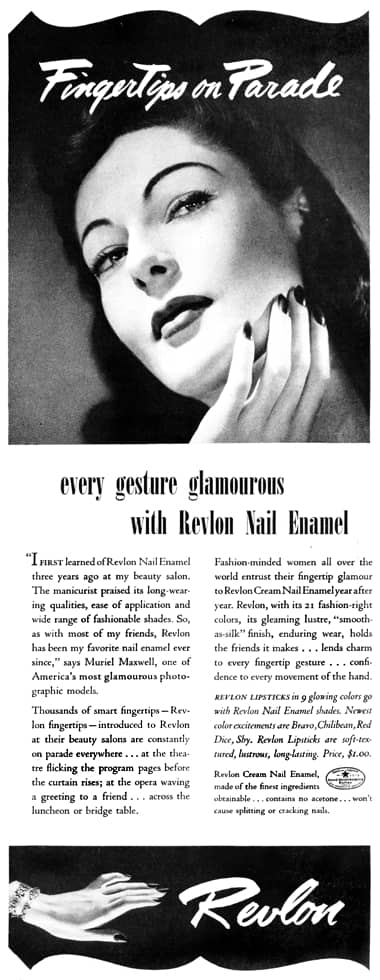

1940 Revlon Fingertips on Parade.

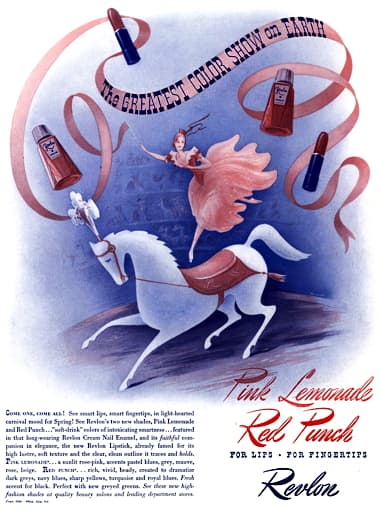

1940 Revlon Pink Lemonade, and Red Punch.

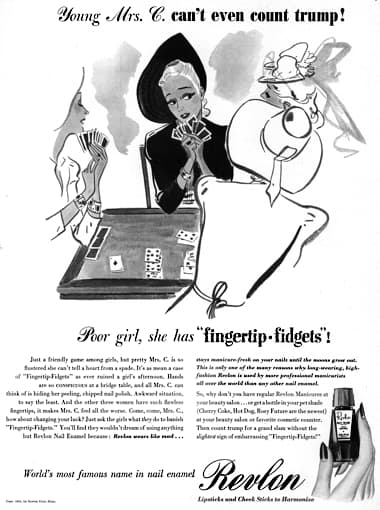

1941 Revlon ‘Fingernail fidgets’.

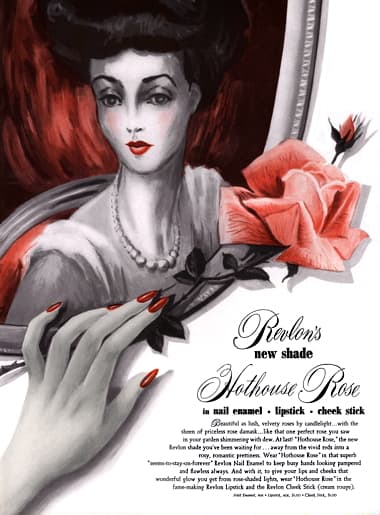

1941 Revlon Hothouse Rose in Nail enamel, Lipstick and Cheek Stick.

1941 Revlon Cherry Coke, Hot Dog and Rosy Future in Nail enamel, Lipstick and Cheek Stick

1941 Revlon Seal-Fast, a top coat

1941 Revlon Seal-Fast

1942 Mrs. Miniver Rose Lipstick and Nail Enamel.

1942 Revlon Victory Set with lipstick in cardboard case.

1942 Revlon “1942’ and “1952’ shades of nail enamel.

1942 Revlon Lipstick and Nail Enamel.

1942 Revlon. Revlon began exporting into Latin America after the Revlon Export Corporation was established in 1938.

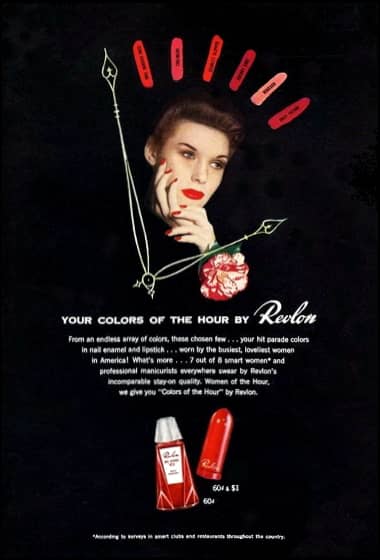

1943 Revlon Mrs. Miniver Rose Enamel and Lipstick. Other ‘colors of the hour’ are Chilibean, Scarlet Slipper, Cherry Coke, Windsor, and Rosy Future.

1943 Revlon Rosy Future.

1944 Revlon Wind-Milled Face Power, Nail Enamel and Lipstick in matching Tournament of Roses shade.

1944 Revlon Pink Garter Lipstick (in wartime plastic case) and Nail Enamel.

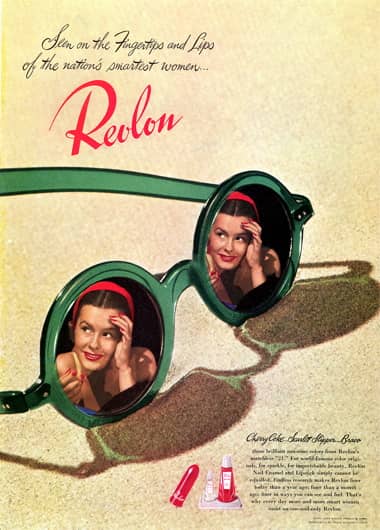

1944 Revlon Cherry Coke, Scarlet Slipper, and Bravo Lipstick and Nail Enamel.

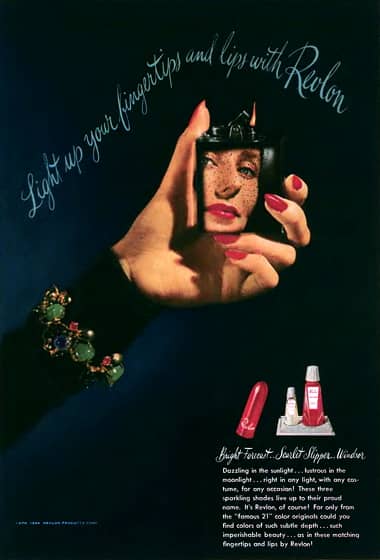

1944 Revlon Bright Forest, Scarlet Slipper, and Windsor.

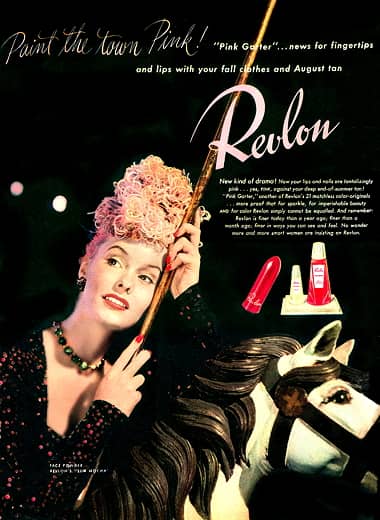

1944 Revlon Paint the Town Pink.

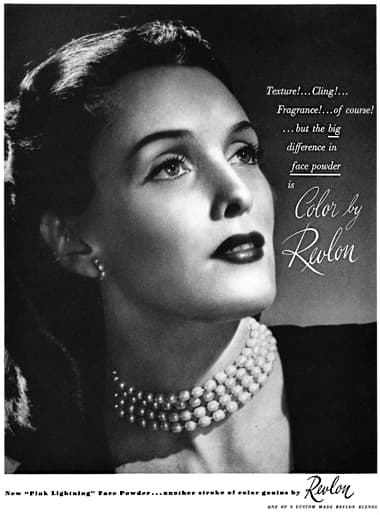

1944 Color by Revlon.

1945 Revlon Dynamite Nail Enamel and Lipstick and Sheer Dynamite Face Powder.