Cold Creams

Described as an emulsion “based on beeswax as emulsifier and thickener” (deNavarre, 1941, p. 237) these creams have a long history of cosmetic use. The first cold cream has been attributed to the Roman physician Galen (C.E. 150) who reputedly made a primitive emulsion by mixing water with molten beeswax and olive oil. It was laborious to make – requiring a great deal of mixing – and tended to separate on standing. However, the formulation persisted – generally using rose-water and/or oil of roses as a perfume – and was included in the first edition of the ‘Pharmacopœa Londinensis’ in 1618.

In later formulations, sweet almond oil replaced the olive oil.

4 oz. of the purest almond oil.

1¼ oz. of white wax.

2 oz. of diluted rose-water.

A few drops of pure essential oil of roses.(Verni, 1946, p. 407)

Vegetable oils like almond oil are liable to deteriorate when they are mixed with water, so early forms were not long-lasting. Their short shelf life meant that cold creams were usually made up at home or purchased in small quantities, freshly made up by a local pharmacist, chemist or druggist. The ceramic pots they were sold in turn up frequently in Victorian-era rubbish tips.

Nearly all creams sold in stores become rancid, and in this state are irritating to the skin instead of soothing. It is better to make your own creams. It can be done with very little trouble and at small expense.

For years a prominent society lady, noted for her exquisite skin and complexion, has used a cream made from the following recipe:

1 oz. Spermaceti.

1 oz. White Wax.

1 oz. Benzoated Lard.

2 oz. Almond Oil.

¼ oz. Camphor Gum.

Dissolve the camphor gum in the oil, and add the other ingredients, heating the whole only to melt. When melted, beat with a fork for one hour, or until perfectly cold, white and creamy. In using it the face must be perfectly free from dust or any foreign matter. Take a small quantity on the tips of the fingers, and spread on the face and neck, rubbing until the cream is absorbed by the skin. The almond oil spreads very easily, and a very little of the cream will cover the face and neck. The face becomes soft and velvety almost immediately. A very fine effect is produced by rubbing the “shine” off with a soft flannel dipped in powder. Using powder in this manner not only produces a better effect, but the skin is not injured by the powder.(Ayer, 1890, pp. 20-21)

Perhaps the only advantage of a short shelf life was that it enabled the formula of the cold cream to be slightly altered according to the season. The proportion of wax was increased in summer, so the cream was more viscous in the warmer weather, and less wax was used in winter when the cold weather tended to harden the cream.

From local to industrial manufacture

The second half of the nineteenth century saw two advances in cold cream formulations that together enabled them to be made on an industrial scale. The first was the replacement of almond oil by petrolatum and mineral oil; the second, the inclusion of borax (sodium borate).

Mineral oils

In 1869, Robert Chesebrough extracted petrolatum from crude petroleum and began selling it under the trade name Vaseline Petroleum Jelly. Once established, Chesebrough produced a range of products made with petrolatum including Vaseline Cold Cream, developed in 1876. Petrolatum had a much longer shelf life than almond oil and was a good deal cheaper. As well as reducing the cost of making cold cream it extended its shelf life. This meant it could now be shipped for sale in distant parts and stand on a shelf in a store without quickly deteriorating.

See also: Petrolatum/Petroleum Jelly

Borax

In the nineteenth century, borax was also introduced into cold creams. In 1890, a formula for a borax cold cream was incorporated into the U.S. Pharmacopoeia and then into the British Pharmacopoeia in 1914 (deNavarre, 1941). However, records go back earlier than this. In 1844, Lawrence Turnbull [1821-1900] published a recipe for a cold cream made with borax in the ‘American Journal of Pharmacy’.

Take of white wax, ℥j oil of almonds, ℥iv borax, ʒii oil of roses, Mv Let the wax be dissolved in the oil of almonds by a gentle heat, so as not to change it; then dissolve the borax in the rose water, and add the solution to the heated oil, stirring constantly until perfectly cool; then add the oil of roses, stirring it in a little longer. If properly prepared it yields a beautiful preparation of a snow-white color, and without any appearance of granulations. The borax unites to form with the oil a mild and bland compound, by chemical union.

(Turnbull, 1844)

In 1883, Adolf Vomácka [1856-1919] also published a recipe for a borax cold cream in ‘New Remedies’. The 1885 report below is a repeat of part of that entry.

Cold Cream—Improved Method of Manipulation.—Mr. Ad. Vomacka communicates the following formula and directions for cold cream:

White wax 200 parts. Spermaceti 500 parts. Oil of almonds, expressed 1600 parts. Rose water 80 parts. Oil of rose, for each 2.4 kilos 30 drops. Melt the wax and spermaceti at a gentle heat on the water-bath, pour the mass into a very shallow, warmed porcelain dish, and let it stand over night covered with paper. Next morning, begin to work the hardened mass by a gentle, uniform to-and-fro motion of the pestle, which should be held lightly between the fingers without exerting pressure, commencing at the edge, gradually working towards the middle, and mixing the whole thoroughly.

The prescribed amount of rose water is now slowly added, in a thin stream, and while constantly stirring. If desired, 5 grms. of borax may be dissolved in the rose water, which will facilitate the combination. [my italics] The mortar is now well covered and set aside for one or two days, in order to give the fat a chance to combine with the water. It is then again briskly stirred for a quarter or half an hour, and finally, the oil of rose is added, previously dissolved in a little castor oil, which later imparts to the cold cream an extremely handsome lustre.

The readiness with which the cold cream becomes rancid or acid makes it advisable to add some suitable preservative, if it is to be kept for any length of time. A very good method is to add a small quantity of salicylic acid dissolved in rose water or sweet spirits of nitre.(Proceedings of the American pharmaceutical association, 1885, p. 56)

Beeswax-borax-petrolatum cold creams

When borax is dissolved in water it produces boric acid and sodium hydroxide. The sodium hydroxide interacts with cerotic acid in the beeswax – a free fatty acid that makes up about 13% of beeswax by weight – and forms an anionic emulsifier, while the boric acid buffers the system. The emulsifier created by the chemical reaction made the oil and water parts of the cold cream less likely to separate on standing, so cold creams made with borax were more stable.

Above: 1938 Cosmetic chemistry students making up a cold cream using beeswax, mineral oil, distilled water and borax in an adult education course in New York (New York Historical Society).

Borax-beeswax cold creams were white, opaque, had a high lustre and spread easily on the skin, but the use of almond oil still limited the shelf life of the cream. When borax-beeswax cold creams were made with petrolatum and mineral oil rather than almond oil, cold creams were produced that were stable, cheap to produce and had a long shelf life. This made borax-beeswax cold creams ideal preparations for industrial manufacture and distribution. A sample recipe is given below:

White beeswax 22.0% White mineral oil 50.8% Distilled water 26.0% Borax 0.8% Perfume 0.4% (Thomssen, 1947, p. 106)

The first commercial cold cream made with petrolatum and borax appears to have been Daggett & Ramsdell’s Perfect Cold Cream, manufactured in New York from 1893.

See also: Daggett & Ramsdell

Other commercial cold creams followed, including one by Pond’s, a name that would become almost synonymous with cold cream.

Pond’s Type o/w Face Cream

Ingredient Wt. % Beeswax 8.00 Mineral oil (paraffinum liquidum) 50.00 Lanolin 3.00 Borax 0.20 Water (aqua) qs 100.00 Procedure: Heat oils to 80°C. Heat water and add borax to 70°C. Add oils to the water with rapid mixing, cool to 40°C and add fragrance.

(Schlossman, 2009, p. 699)

See also: Pond’s Extract Company

How cold creams got their name

Cold creams were usually made as water-in-oil (W/O) emulsions. After the creams are applied to the skin much of the water evaporates leaving the remaining oil to act as a solvent which cleanses the skin of cosmetics and other grime. There may also be some surfactant activity. Some chemists suggested that as the water evaporated it cooled the skin which is why the creams are called ‘cold creams’. An alternative explanation is that in the days before mineral oil or petrolatum were used, the creams needed to be stored in a cool place to stop them going rancid. This made them cold to the touch and so gave them their name.

Uses for cold creams

Cold creams that contained a high percentage of mineral oil (liquid paraffin) or petrolatum were regarded primarily as cleansers, to be spread on thickly, then removed with a cloth or tissues. However, depending on the formulation, they could be used for a variety of purposes and were often advertised as beauty creams or night creams.

City air in most large western cities was a good deal grimier than it is today. Dust, soot and other particulate matter collected on the face, making it an enduring problem. Early advertisements for cold cream stressed the need to “cleanse your skin of all the dirt which lodges in the pores through the day, and which, more than anything else, injures the skin” (Pond’s advertisement, 1917). It was also suggested that the cream be used at night to give it additional time to act.

The Cold Cream, applied whenever convenient during the day, always after exposure to the open air and before retiring at night, brings to the surface particles of dust and dirt which can easily be removed with a soft towel. Its gentle oils will sink deep into the pores especially during sleep and cleanse the skin thoroughly.

(Pond’s advertisement, 1927)

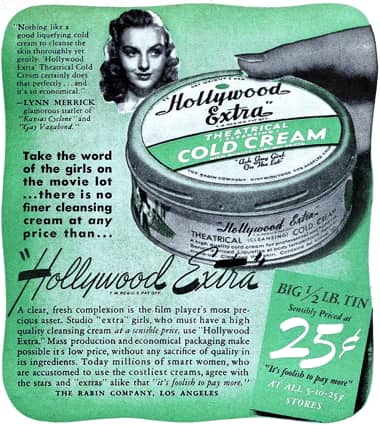

Cold creams were widely used in the theatrical trades to remove greasepaint with a number of suppliers producing products labelled as Theatrical Cold Cream. As the use of street make-up increased, cold creams were also promoted as a way to remove face powder, lipstick, rouge, foundation and other forms of personal make-up.

Skin could also be cleansed with soap and a lot of early advertising by cosmetic companies was designed to persuade women to switch from soap to a skin cream by suggesting that soap and water did not cleanse the skin thoroughly or was downright harmful. A Marie Earle advertisement proclaimed “Don’t wash your face recklessly with soap and water, which … may dry and roughen and wrinkle your skin” (Marie Earle advertisement, 1927). Coty advertised that their cold creams “cleanse the pores thoroughly of dust, cosmetics and excess oil – which do not yield to water alone” (Coty advertisement, 1928). Despite these warnings it is probable that most women used both; that it was “common practice with many women to use a cold cream first for makeup removal, and then to complete the cleansing process by using soap” (Sagarin, 1957, p. 81).

Cold creams in beauty regimes

Cold creams formed the basis of early beauty regimes developed by Pond’s, Elizabeth Arden, Helena Rubinstein and others. By establishing a daily regime, cosmetic companies hoped they would increase the usage of their creams and widen consumer consumption to entire product lines. Guidance from beauty authorities saw many women adopt the practice of applying cold cream before sleep to remove the dirt, grime and cosmetics of the day. It cleansed the skin and, if not removed with soap and water, left a thin film with moisturising properties. If it was doing something else while you slept, so much the better. One wonders, for example, how many women discovered that leaving it liberally on their face when they retired, helped them avoid the ‘ministrations’ of their husbands, enabling them to get a night of uninterrupted sleep.

Since the cream will appear greasy even after an application of cold cream is wiped off with a soft towel, it is best for the sake of one’s friends to apply it at night, although husbands have been know to object to the procedure.

(Phillips, 1934, pp. 30-31)

See also: Day and Night Creams

In the 1920s, adding ingredients like lanolin to cold creams enabled manufacturers to make additional claims for their products. Substances like lanolin were thought to have ‘nutritive’ value, so cold creams that contained it could also be promoted as ‘skin foods’.

Pond’s cold cream – a food and cleanser for tired pores – should be gently massaged into the face, neck hands and arms each night on retiring. Because it supplements the natural oil of the skin it aids in preventing and eradicating little lines that time and care are constantly trying to etch around the eyes and mouth. Pond’s Creams never promote the growth of hair.

(Pond’s advertisement, 1927)

See also: Skin Foods

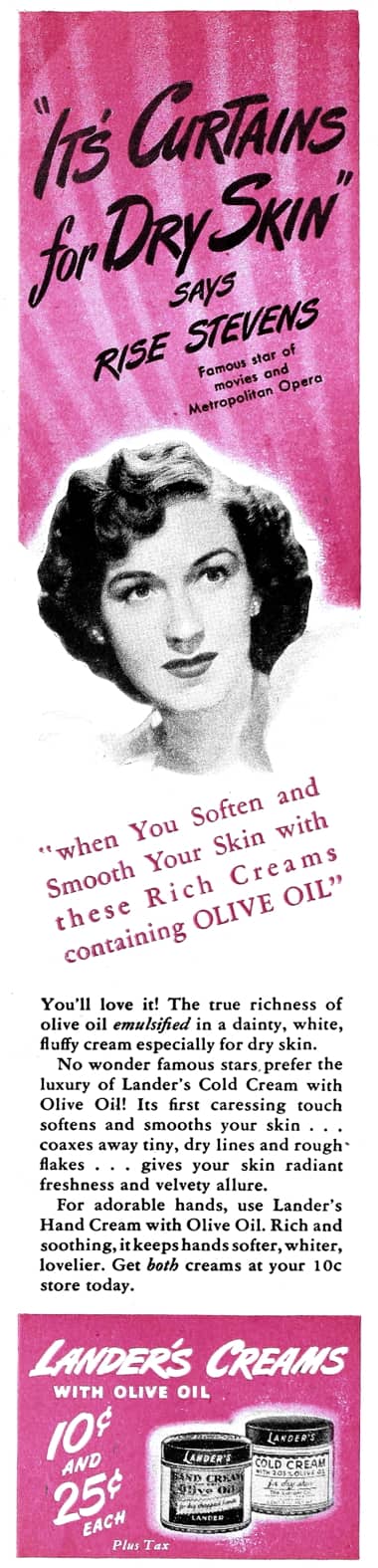

The ‘rich’ nature of cold creams also saw them frequently recommended in dry-skin treatments. Some soap companies used this idea when advertising that their soap contained cold cream, intimating that the cold cream would reduce the ‘drying’ effects of the soap.

Alternatives

The all-purpose nature of cold cream, which had been its strength, proved to be its weakness. The recognition of different skin types and skin conditions along with the proliferation of skin creams containing ‘beneficial additives’ saw the need for an all-purpose skin cream decline. This fracturing of the commercial skin-care market which began with the introduction of stearate (vanishing) creams in 1892, picked up pace in the 1920s and 1930s and eroded the prestige of cold creams and pushed them increasingly into the low-end of the skin-care market.

See also: Vanishing Creams

The development of specialist cleansers also attacked cold cream’s near monopoly as a skin-cream cleanser. Starting with liquefying cleansing creams which became popular in the 1930s – specifically advertised as being better than greasy cold creams – the development of alternative skin cleansers for different skin types and specific skin problems further diminished the standing of cold creams.

See also: Liquefying Cleansing Creams

Cold creams today

Although the use of cold creams has declined, they are still available. However, when more recent products are compared to original formulations marked differences are evident, primarily in the replacement of borax with modern surfactants.

Pond’s Cold Cream Cleanser

Ingredients: Mineral oil, Water, Ceresin, Beeswax, Triethanolamine, Ceteth-20, Fragrance, Behenic acid, Montan wax, Cetyl alcohol, Carbomer, DMDM hydantoin, Iodopropynyl butylcarbamate.

Improvements in preservatives have also allowed some cold creams to eliminate mineral oil, a substance disliked by many consumers.

Weleda Cold Cream

Ingredients: Water (aqua), Prunus amygdalus dulcis (sweet almond) oil, Arachis hypogaea (peanut) oil, Beeswax (cera flava), Glyceryl linoleate, Fragrance (parfum), Hectorite, Limonene, Linalool, Citronellol, Geraniol, Citral.

Still others have such complex formulations that they appear to have little relationship with traditional cold creams.

Avene Cold Cream Ultra Rich Cleansing Gel

Ingredients: Avene Thermal Spring Water (Avene Aqua), Carthamus Tinctorius (Safflower) Seed Oil (Carthamus Tinctorius Seed Oil), Mineral Oil (Paraffinum Liquidum), Cocos Nucifera (Coconut) Oil (Cocos Nucifera Oil), Cyclopentasiloxane, Sesamum Indicum (Sesame) Seed Oil (Sesamum Indicum Seed Oil), Sorbitan Stearate, Cyclohexasiloxane, Glyceryl Stearate, Peg-100 Stearate, Allantoin, Beeswax (Cera Alba), Benzoic Acid, Cetyl Alcohol, Citric Acid, Fragrance (Parfum), Phenoxyethanol, Sodium Hydroxide, Sodium Polyacrylate, Tetrasodium Edta, Water (Aqua).

Updated: 9th October 2018

Sources

Ayer, A. G. (Ed.). (1890). Facts for ladies. Chicago: Any G. Ayer.

Jellinek, J. S. (1970). Formulation and function of cosmetics (G. L. Fenton, Trans.). New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Phillips, M. C. (1934). Skin deep: The truth about beauty aids. New York: Garden City Publishing.

Poucher, W. A. (1974). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (8th ed., Vols. 1-3). London: Chapman and Hall Ltd.

Proceedings of the American pharmaceutical association. (1885). Philadelphia: Author.

Sagarin, E. (Ed.). (1957). Cosmetics: Science and technology. New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc.

Schlossman, M. L. (Ed.). (2009). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (4th ed., Vol. II). Carol Stream, Il: Allured Publishing Corporation.

Thomssen, B. S. (1947). Modern cosmetics (3rd ed.). New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

Turnbul, L. (1884). Remarks on cold cream. American Journal of Pharmacy.. 16:(1), 17.

Verni, M. (1946). Modern beauty culture (2nd ed.). London: New Era Publishing.

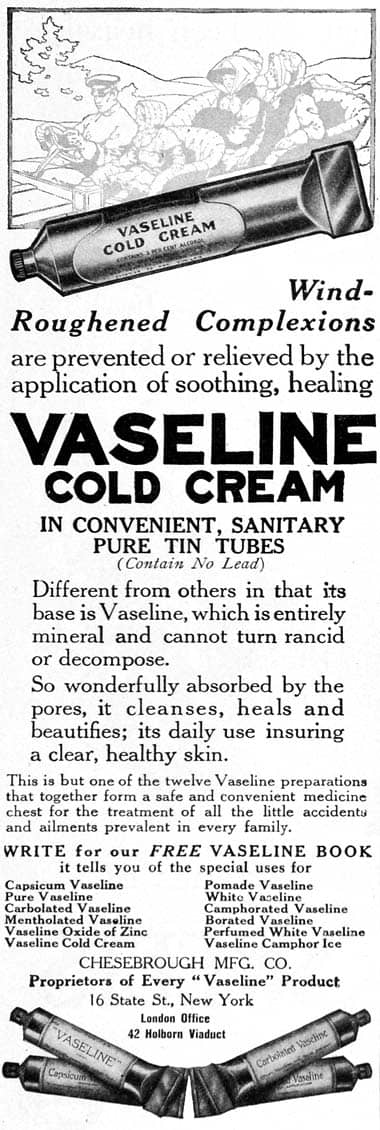

A jar of Vaseline Cold Cream. First produced by the Chesebrough Manufacturing Company in 1876, it was the first cold cream made with mineral oil and petrolatum.

1910 Vaseline Cold Cream and other products in convenient, sanitary pure tin tubes.

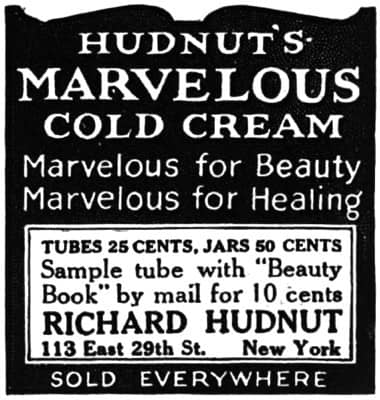

1916 Richard Hudnut Cold Cream.

1922 Daggett & Ramsdell Perfect Cold Cream.

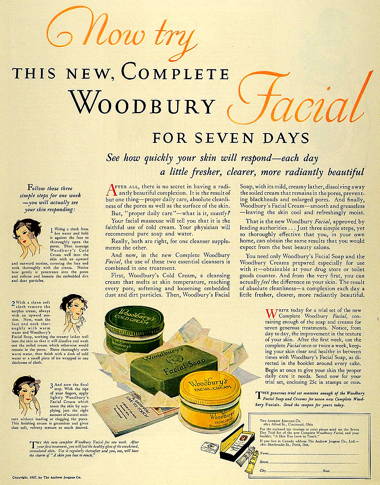

1927 Complete Woodbury Facial consisting of Woodbury’s Cold Cream, Woodbury’s Soap and Woodbury’s Facial Cream.

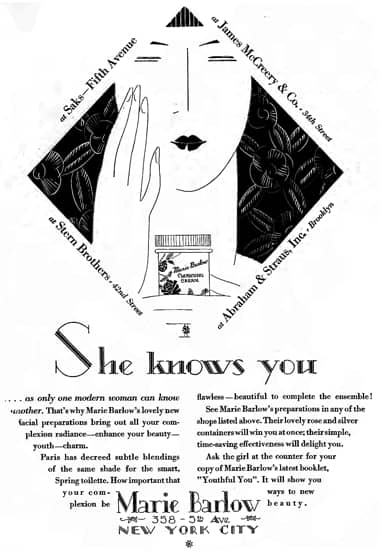

1927 Marie Barlow Cleansing Cream made using a cold cream formulation.

1928 Black and White Cold Cream.

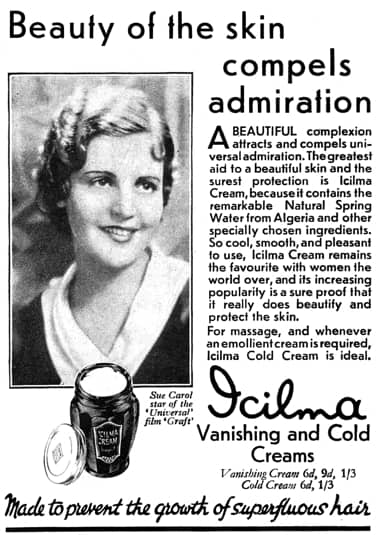

1931 Icilma Vanishing and Cold Cream.

1931 Princess Pat Cold Cream, Skin Food and Astringent.

1941 Hollywood Extra Theatrical Cold Cream.

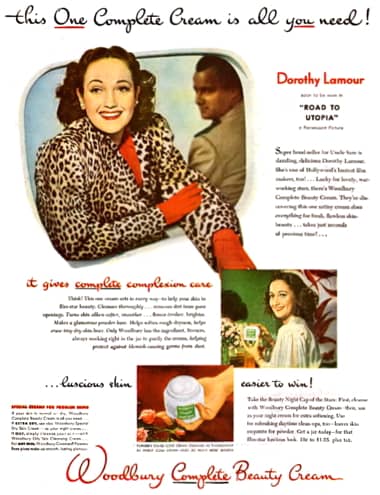

1945 Woodbury Complete Beauty Cream.

1946 Lander’s Hand Cream and Cold Cream.

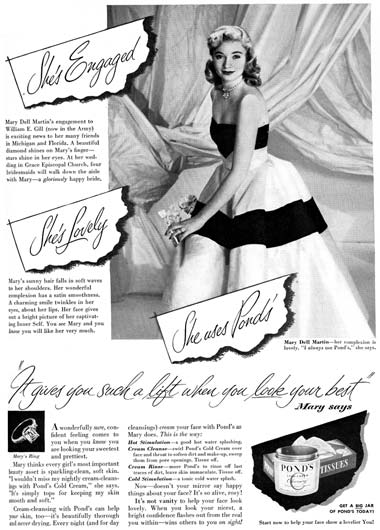

1951 Pond’s Cold Cream.

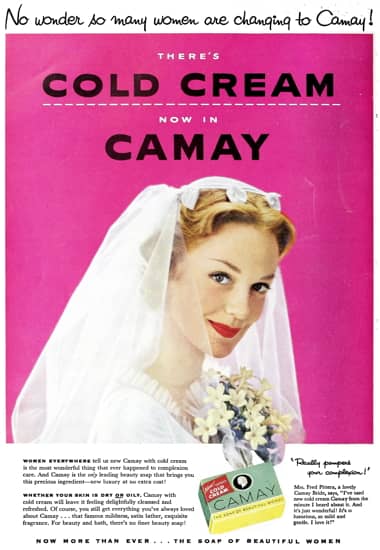

1954 Camay Cold Cream Soap.

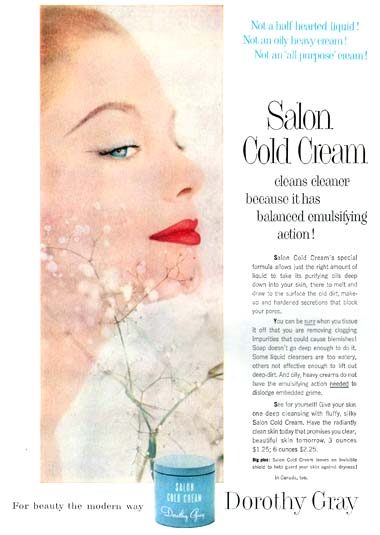

1957 Dorothy Gray Salon Cold Cream. Names like ‘Salon’ and ‘Theatrical’ were added to cold creams to try and elevate their status.

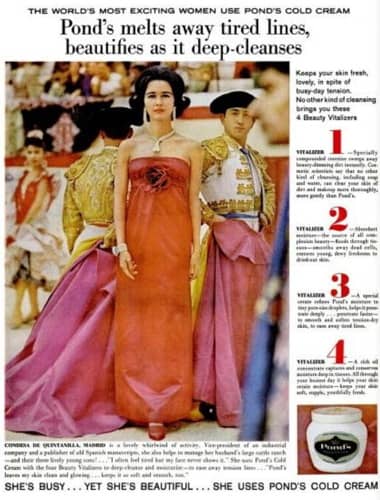

1960 Pond’s Cold Cream.