Vanishing Creams

Stearate skin creams were more commonly known as vanishing creams because they seemed to disappear when spread on the skin. The name may have been coined by the Pond’s Extract Company, who began making a stearate cream called Pond’s Vanishing Cream in 1904. Pond’s was not the first company to market this type of skin cream; that honour goes to Burroughs Wellcome who began selling a stearate cream called Hazeline Snow in 1892.

Above: 1927 Burroughs Wellcome Hazeline Snow.

See also: Hazeline Snow and Pond’s Extract Company

Pond’s was also not the first company to make a stearate cream in the United States. Crême Elcaya had debuted earlier in New York in 1901.

See also: Elcaya

Functions

Vanishing creams were advertised as beauty creams and skin protectants but for many women their most important function was to act as a base for face powder. Early loose powders did not adhere well and their cling could be improved if they were applied over a surface cream. A cold cream could have been used but it had a greasy feel so was unsuitable for most women unless their skin was very low in oil. Vanishing creams had a non-oily feel so were generally considered to be a better solution.

No doubt there were circles in which make-up was freely used but it certainly was not in ours, and the flasks and jars contained eau-de-cologne rather than scent, and cold cream as a general lubricant. People who suffered from chapped hands carried glycerine. I had never seen or heard of foundation medium until I went to Paris and then my room-mate and I dashingly brought the smallest-sized tube of Pond’s Vanishing Cream, which we shared. This was a great advance because the powder stuck to our noses and we need not so often squint down with one eye to see if they had acquired the shine which was so much frowned-upon.

(Lewis, 1980, p. 172)

Chemical composition

Stearate/Vanishing creams were known for their smooth, dry feel on the skin and their pearly sheen. Chemically they were regarded as oil-in-water emulsions consisting of stearic acid (a saturated fatty acid), an alkali, a polyol and water. More recently, Jean-Pierre Forestier has suggested that stearate creams are opaque gels not emulsions (Forestier, 2017).

The alkali reacts with some of the stearic acid – the best was triple pressed (t.p.) – to form a soap which then functioned as an emulsifier. Forestier writes that this formed a water-in oil emuslion which then underwent a phase inversion to become a gel rather than an oil-in-water emulsion as was traditionally believed (Forestier, 2017) .

The polyol (e.g. glycerin) helped to soften and protect the skin and prevent chaps, a function it also performed when used to make glycerine creams and jellies. Glycerine also acted as a humectant which helped prevent the vanishing cream from drying out while it sat on the shelf. However, packaging the cream in a jar with a screw-top lid or in a tube was also important to seal in the moisture. The lids in early vanishing creams were made from aluminium because the metal did not rust but these were later replaced with lids made from plastic.

See also: Glycerine Creams and Jellies

There were limits to how much polyol could be included in the formulation. If too much was used the polyol would absorb water from the air causing the face powder applied over the vanishing cream to spot, making frequent repowdering necessary (Poucher, 1926, p. 36).

The selection of the alkali also affected the consistency of the cream. Vanishing creams made with sodium soaps – using alkalis like sodium hydroxide or borax – produced harder creams with a poor sheen, while those made with potassium soaps – using an alkali such as potassium hydroxide – produced softer creams with a good consistency and sheen (deNavarre, 1941, p. 243).

Some early vanishing creams – often called ‘snows’ or ‘foams’ – used carbonates or bicarbonates as the alkali. This released carbon dioxide during the production process. Some of this quickly escaped but small bubbles of carbon dioxide remained giving the cream a foamy consistency. Unfortunately, over time the carbon dioxide bubbles rose to the top of the mixture causing the cream to sink. Using hydroxides as the alkali avoided this problem and potassium hydroxide became a favoured ingredient in many vanishing cream formulations.

Per Cent Stearic acid t. p. 17.0 Sodium carbonate 0.5 Potassium hydroxide 0.5 Glycerin 6.0 Water 71.0 Alcohol 4.5 Perfume 0.5 Procedure: Melt the stearic acid. Make a solution of the alkalies in one-third of the water, add the glycerin. Then add the solution with a steady agitation to the melted fats, continue stirring until emulsification has taken place; then add the remainder of the water heated to the same temperature. Continue stirring until the temperature has dropped to about 40°C. Dissolve the perfume in the alcohol and stir this in. Allow the batch to stand aside for a day before filling.

(Chilson, 1934, p. 88-89)

Occasionally, a gum might be included in the formulation to improve the stability of the emulsion and help the cream go on more smoothly:

Per Cent Stearic acid t. p. 19.0 Glycerin 6.5 Potassium hydroxide 1.0 Water 65.5 Gum tragacanth powder 2.0 Alcohol 5.5 Perfume 0.5 Procedure: Mix the perfume, alcohol, and add the tragacanth and mix with half of the water. Heat the rest of the water, dissolve the alkali in it and add the glycerin. Melt the stearic acid and mix in the alkali solution. When emulsified, heat the tragacanth solution slightly and add with steady mixing.

(Chilson, 1934, p. 91)

In the 1930s, triethanolamine largely replaced the older potassium soaps. As well as being less irritating to the skin, it helped ensured that the cream always had a pearly sheen (deNavarre, 1975, p. 283).

Stearic acid 22.5% Triethanolamine 1.5% Potassium hydroxide 1% Glycerin 6% Water 69% (Thomssen, 1947, p. 177)

Pearly sheen

The nature of the pearly or satin-like sheen of vanishing creams fascinated cosmetic chemists of the time. As the sheen was associated with quality, chemists were keen to reproduce the effect. Poucher (1924) suggested employing oleic acid and provided information on how the sheen changed compared with the percentage used.

One per cent yields a pearliness.

Two per cent gives a satiny appearance.

Four per cent produces a cream having an appearance approximately closely to that of powdered aluminium. The ideal formula will therefore read:

Stearic Acid 200 gr. Oleic Acid 40 gr. Potassium hydroxide 10 gr. Water 800 cc. The fatty acids are melted together and the hot solution of alkali poured in while the whole is briskly stirred and the heat maintained. The agitation is continued while cooling and until a creamy product results. The perfume is then added.

Providing the room is not too cold, the sheen will have developed overnight. If the temperature falls too low, the cream is again slightly warmed and stirred when a perfect product results.(Poucher, 1924, p. 7)

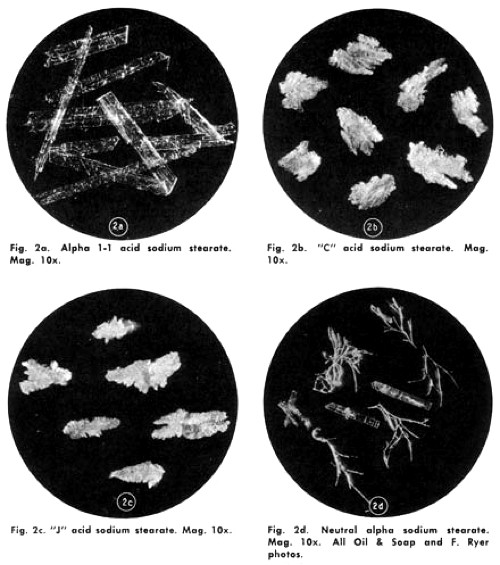

It was eventually discovered that the pearliness was due to the formation of platelet-like sodium stearate crystals in the mixture. These reflected and refracted light to produce the sheen. If they were absent, it disappeared.

Above: A range of sodium stearate crystals (deNavarre, 1975).

See also: Pearl Essence

The use of self-emulsifying polyol stearates became common in the 1930s. A good example of one of these compounds was Tegin, developed by the German company Goldschmidt AG in the late 1920s. Their addition allowed all the materials to be heated and mixed together until they were ready to be poured into containers, making the process of manufacturing vanishing creams a lot simpler (deNavarre, 1975, p. 283). Creams made with Tegin were also softer than traditional stearate creams but unfortunately they often lost the traditional pearly sheen.

Advertised functions

As well as being known as vanishing creams, stearate creams were also sold under a variety of other names. Being a powder base, they were more commonly used during the day so the Pomeroy Company advertised their stearate cream as a day cream. Others referred to their stearate cream as a finishing cream, because it was the last skin-care cosmetic applied before powdering. Max Factor went one step further. He added White, Flesh, Rachelle, and Natural shades to his stearate cream thereby creating Max Factor Make-up Foundation Cream.

In addition to keeping powder on the face, vanishing creams were widely advertised as protecting the skin from the elements including ‘chapping winds’ and ‘sooty breezes’. The presence of the humectant glycerine was also used to claim that they helped reduce moisture loss from dry skin.

Pond’s Vanishing Cream is made especially for the outer skin. It is greaseless. It contains a marvellous substance that prevents loss of skin moisture – actually replaces lost moisture.

You can rest this yourself by a single application of Pond’s Vanishing Cream on dry chapped skin! The roughness is smoothed away! Your skin is pearly looking. And this cream holds powder and rouge smoothly for hours!.(Pond’s advertisement, 1934)

See also: Motor Skin

As vanishing creams had a semi-matt finish, they could also be used without powder to reduce the effects of oiliness and shine on skin where this was a problem, making them popular with African-Americans.

What happened to vanishing creams?

After the First World War, new ingredients and formulations allowed cosmetic companies to develop specialised skin-care cosmetics. Selling creams simply as ‘cold’ or ‘vanishing’ became less and less attractive and products named by function, rather than by look or feel, became the norm. This led to companies promoting their skin-care creams as powder creams, tissue creams, foundation creams, night cream, hand creams, cleansing creams, youth creams, eye creams and so forth.

Naming skin-care creams by function helped cosmetic companies to widen their skin-care ranges and sell more cosmetics. It also gave consumers an impression of product sophistication. Cold creams and vanishing creams then became progressively seen as simple and old fashioned and consumers thought it unlikely that they could achieve the results promised by the new specialist lines. Consequently, sales of vanishing creams began to fall in the late 1930s.

See also: Cold Creams

Pond’s, a major manufacturer of vanishing creams, may have inadvertently contributed to their decine. In 1916, to improve sales, they began to advertised their vanishing and cold creams together as part of a ‘skin-care system’ – cold cream to cleanse and ‘feed’ the skin at night, vanishing cream to protect and provide a base for powder during the day. The Pond’s “every normal skin needs these two creams” campaign was a great success and Pond’s sales of these creams tripled between 1916 and 1920 (Peiss, 1998, p. 121).

After the war, Pond’s creams became a victim of their own success. Consumers took the idea of using different creams during the day and night to heart but applied it to specialist creams more suited to their skin type. Pond’s then had to resort to celebrity endorsements to maintain sales (Kay, 2005, p. 50).

See also: Day and Night Creams

Improvements in face powders also played a part in the demise of vanishing creams. The increased use of stearates in face powders and the ability of manufacturers to produce powders with finer particles improved the adherence of face powders and this also reduced the need for a vanishing cream base.

See also: Loose Face Powders

The adoption of specialist foundations added to this trend. Even though some of these used a stearate cream as a base they were referred to as foundations not vanishing creams; the previously mentioned Max Factor Make-up Foundation Cream being a good example.

See also: Powder Creams

Despite the demise of products labelled ‘vanishing cream’, stearate creams continue to be manufactured to this day – with hand or body creams and lotions, and shaving creams being good examples – so in that sense, vanishing creams never really disappeared. In addition, the rising interest in vintage products has see a re-emergence of the word ‘vanishing’ on the labels of a number of skin-care lines. Some of these are true stearate creams but others are not. Only a careful reading of the label will tell.

First Posted: 20th April 2009

Last update: 8th April 2025

Sources

Chilson, F. (1934). Modern cosmetics. New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston: D. Van Nostrand Company.

deNavarre, M. G. (1975). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. (2nd. ed., Vol. III). Orlando: Continental Press.

Forestier, J-P. (2017). La crème au stéarate est un gel. Retrieved April 1, 2025 from https://www.beaubiophilo.com/2017/10/la-creme-au-stearate-est-un-gel.html

Kay, G. (2005). Dying to be beautiful: The fight for safe cosmetics. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press.

Lewis, L. (1980). The private life of a country house (1912-1939). London: David & Charles.

Peiss, K. (2007). Hope in a jar: The making of America’s beauty culture. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Poucher, W. A. (1924). Pearly vanishing creams. La Parfumerie Moderne. 17(1), January, 6-7.

Poucher, W. A. (1926). Eve’s beauty secrets. London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd.

Thomssen, B. S. (1947). Modern cosmetics (3rd ed.). New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

1910 Crême Elcaya. America’s first ‘disappearing cream’ introduced in 1901.

1911 Pond’s Vanishing Cream as a complexion enhancement.

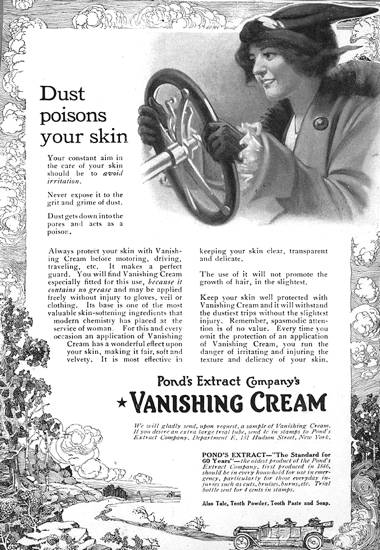

1912 Pond’s Vanishing Cream as a dust protectant.

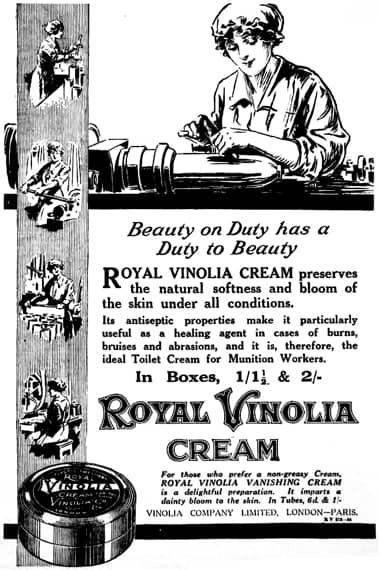

1918 Royal Vinolia Vanishing Cream.

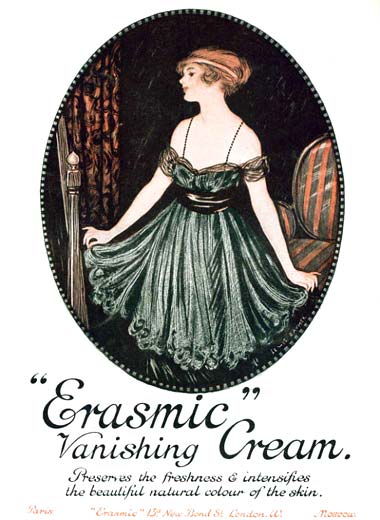

1919 Erasmic Vanishing Cream.

1922 Hinds Disappearing Cream.

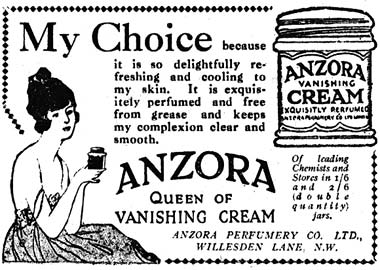

1922 Anzora Vanishing Cream.

1925 Eastern Foam Vanishing Cream. This cream was probably made using a carbonate or bicarbonate which releases carbon dioxide during the manufacture resulting in a foamy/snowy consistency.

1926 Edna Wallace Hooper advertising both her cold and vanishing creams as ‘Youth Creams’.

1928 Koken Creme Snow.

1936 Crookes Laboratories Collosol Zinc Cream.

1939 Shadforth ‘Snow’ Vanishing Cream.

1942 Pond’s Vanishing Cream promoted as a 1-Minute Mask and an ideal powder base.

1948 Icilma Foundation Cream. As the twentieth century progressed vanishing creams were often rebadged as foundation creams to make them more attractive.

1954 Swift & Company, manufacturers of cosmetic grade stearic acid.