Arsenic-Eaters and Cucumber Creams

Cucumber juice, along with other substances like lemon juice and buttermilk, has long been used in treatments for the two main enemies of a pale, flawless skin; sunburn and freckles. It was recommended as a cure for these afflictions even before 1653 when Nicholas Culpeper [1616-1664] first listed cucumbers in his ‘Complete Herbal’ and it continued to be used in skin treatments right up to the present day.

When the season of the year is, take the cucumbers and bruise them well and distil the water from them, and let such as are troubled with ulcers in the bladder drink no other drink. The face being washed with the same water cureth the reddest face that is; it is also excellent good for sun-burning, freckles, and morphew.

(Culpeper’s Complete Herbal, 1814, p.140)

When used in a whitening treatment, cucumbers could either be sliced and placed directly on the face, applied in cloth strips soaked in cucumber juice or added to a face cream, lotion or paste. Necks were often included to remove the stains that came from wearing high collars and shoulders were occasionally targeted as well.

One of the great recommendations of the cucumber as a complexion improver is that it whitens the skin. There are a number of simple ways in which the cucumber can be used at home. One girl recommends a slice of cucumber instead of soap for washing the face now and then. Or, bathe your face, and after drying rub the cucumber over and let the juices dry in.

A lotion for whitening the neck is found in a cucumber application. Take fresh, ripe cucumbers and cut them in long strips. Bind them on the neck and shoulders and arms, and let the juice dry on. This has a bleaching effect.

Cucumber cream, to whiten the complexion after removing sunburn, requires about a pink of green cucumbers chopped and the juice extracted with a lemon squeezer. To this add enough sweet cream to make a paste, and a few drops of rose water. This paste may be diluted as used with sweet milk and is to be used on the face at night and washed off in the morning.(The Reading Eagle newspaper, September 13, 1903)

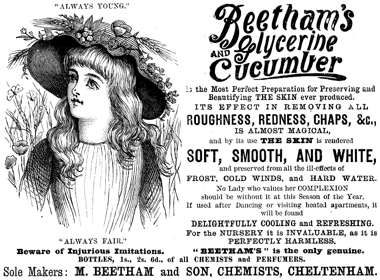

A variety of commercial cucumber creams and lotions – such as Beetham’s Cucumber and Glycerine Cream – were available in the nineteenth century and cucumber continued to be used in some commercial skin creams right through the twentieth century. Given that cucumber extract was rather expensive, whether these preparations contained enough cucumber juice to make an appreciable difference is another matter.

Glycerine and Cucumber Creams sometimes contain cucumber juice, but more frequently this is conspicuous by its absence. For those who wish to include it in their formula the following method of preparation is recommended:—

Take 1 kilo of cucumbers, wash them and cut them into small pieces, place these in a tincture press and squeeze out all the juice.

Heat this on a water bath for ten-minutes in order to coagulate albuminous matter. Filter and cool. Stand the container in cold water for one hour and filter again. Add sufficient alcohol 90 per cent to produce 1 litre, stand aside for three days and filter bright. This constitutes cucumber juice, and it can be stored without alteration for some time.(Poucher, 1932, p. 512)

Cucumbers and arsenic

Although cucumbers were recommended as a treatment for freckles and suntan, nineteenth century beauty writers did not generally give any reason for their effectiveness. Hovever, as the century drew to a close, newspaper articles began to appear stating that cucumbers contained a ‘natural arsenic’ and that this was the reason for their ability to bleach the skin. This ‘fact’ then goes on to reappear intermittently for the next fifteen years or so.

The natural arsenic In the cucumber makes this a splendid face bleach, and the beauty of it is that it is perfectly harmless.

(The San Francisco Call newspaper, August 14, 1898)

Be sure in making any cucumber cosmetic that the cucumber juice is strong, for it is the natural arsenic in the cucumber which Imparts the wonderful refining and whitening power.

(The Washington Times newspaper, October 26, 1902)

Every one has heard of what the cucumber will do for the beauty of the skin, but comparatively few know how it is used. There is a sort of natural arsenic in the cucumber that makes it valuable as a skin whitener.

(The New York Times newspaper, September 5, 1909)

The cucumber juice must be strong, for it is the arsenic in the vegetable which gives it a bleaching power.

(The Sunday Oregonian newspaper, July 14, 1912)

Beauty writers who claimed that cucumbers contained a ‘natural arsenic’ came mainly from the United States and it is possible to see how an erroneous idea like this could spread from one American newspaper to another. However, the fact that some beauty writers linked cucumbers with arsenic is also an indication of the status arsenic had achieved as a skin beautifier.

Arsenic

The use of arsenic as a beauty treatment in the nineteenth century seems to have begun after reports were published in the 1850s of Styrian and Lower Austrian peasants eating arsenic to improve their figures and freshen their complexions. The story became widely known in the English speaking world when an account of these arsenic-eaters was retold by James F. W. Johnston [1796-1855], a Scottish agricultural chemist, in the second volume of his book ‘The Chemistry of Common Life’, first published in 1855, or when the practice was also reported in the 1856 ‘Chambers Journal’ (Parascandola, 2012).

Arsenic is thus consumed chiefly for two purposes—First, To give plumpness to the figure, cleanness and softness to the skin, and beauty and freshness to the complexion. Second, To improve the breathing and give longness of wind, so that steep and continuous heights may be climbed without difficulty and exhaustion of breath. Both these results are described as following almost invariably from the prolonged use of arsenic either by man or by animals.

For the former purpose young peasants, both male and female, have recourse to it, with the view of adding to their charms in the eyes of each other; and it is singular to see how wonderfully well they attain their object, for those young persons who adopt the practice are generally remarkable for clear and blooming complexions, for full rounded figures, and for a healthy appearance.(Johnston, 1856, p. 167)

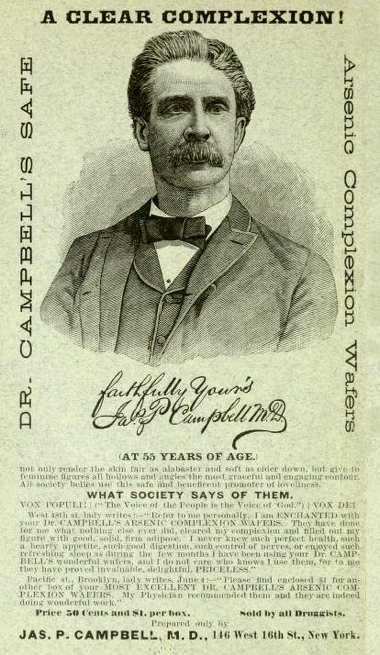

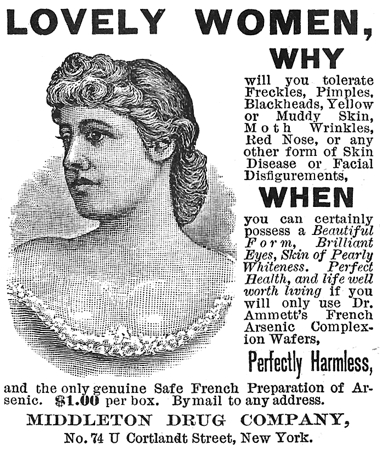

Although some medical authorities of the day questioned the veracity of the arsenic-eaters story – originally reported by Johann Jakob Von Tschudi in 1851 – the publicity associated with it ushered in a range of arsenical products in the second half of the nineteenth century specifically aimed at improving the complexion. These included products to be ingested, such as complexion wafers, liquids and pills, as well as arsenic washes and soaps.

These arsenical beauty aids were believed to make the skin look pale, something that was highly desirable in the European world of the time. Although admittedly talking about the demi-monde of New York, and not women of respectability, George Ellington, writing in 1869, sums up arsenic’s attraction.

Arsenic … has held its own until the present time, principally for the reason that it sicklies the brow o’er with the “pale cast of thought,” and makes the person look pale and interesting.

(Ellington, 1869, pp. 223-224)

Fortunately, although there were numerous new arsenical products on the market it is likely that the amount on arsenic in many of them was very low or absent altogether, as this extract from an 1863 British court case points out:

Mr, H. W. Bolton, trading as Bristow and Co. Clerkenwell, said he manufactured the arsenical complexion soap sold by the defendant. It was made to be sold as a toilet soap, not as a medicinal preparation. Two-and-a-half grains of arsenic were put into every 3cwt. of soap. He did not pretend that this small quantity of arsenic made any difference to the soap. Mr Montgomery.—Then why put it in at all? Witness.—Because it is arsenical soap. Mr. Montgomery.—But why sell it as arsenical soap? Witness.—Because there is a demand for it. People think arsenic is good for the complexion, so we make arsenical soap for them.

(The Times newspaper, December 7, 1863)

Cucumbers and arsenic

Exactly where the myth that cucumbers contained a ‘natural arsenic’ got started is unknown to me. Cucumbers are green and a number of green dyes including Scheele’s green, Schweinfurth green, Vienna green, Imperial green and Emerald green were used to colour paper and cloth in the nineteenth century were made from arsenic but it seems unlikely that colour alone would be the connection. It is also possible that some individuals added arsenic mixtures, such as Fowler’s solution – developed by Thomas Fowler [1736-1801] in 1786, it contained 1% potassium arsenite – in with a cucumber cream and that this was misinterpreted. It is more likely that someone commented that cucumbers lightened the skin like arsenic and this led to the idea that cucumbers contained a ‘natural arsenic’. Whatever the cause, once the idea appeared in print, it was soon repeated.

As cucumbers contain much arsenic they are a natural bleach for the skin, and when combined with other ingredients make an admirable cream.

Melt together, over warm water, the following:

White wax ozs. 2 Spermaceti ozs. 2 Remove from water and add, while whipping hard,

Olive Oil ozs. 2 Sweet Almond Oil ozs. 6 When nearly cold add 2½ ounces rose water and 4 ounces of cucumber ointment made as follows:

Cover six medium-sized and fresh cucumbers with 2½ ounces of alcohol after having chopped the cucumbers, skins and all, very fine. Let the mixture stand a day or two, and then strasin through gauze; add to the above with the rose water. Scent.(Furlong, 1914, p. 17)

As women engaged in more outdoor activities and sports at the turn of the century, and as darker skins became more popular in the 1920s, lightening the skin required more extreme treatments than those that could be delivered by either arsenic or cucumber juice and skin lightening products containing another poison, mercury, became increasingly popular.

See also: Freckle Removers and Mercolized Wax

Although cucumber extract continues to be used in some skin preparations today, and modern research has indicated that it does contain a mild bleaching agent, it is more likely to appear in products that soften and hydrate the skin rather those that claim to whiten it. When it is included, it makes up a very small proportion of a formulation.

2nd June 2014

Sources

Arsenic eating and arsenic poisoning. (1862). The British and Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review, 29, January-April, 130-153.

Culpeper’s English physician; and complete herbal. (1814). London: Richard Evans.

Ellington, G. (1869). The women of New York or the under-world of the great city. Illustrating the life of women of fashion, women of pleasure, actresses and ballet girls, saloon girls, pickpockets and shoplifters, artists’ female models, women-of-the-town, etc., etc., etc. New York: New York Book Company.

Furlong, P. (1914). Beauty culture at home. A complete course in shampooing, facial and scalp massage, hair coloring, manicuring, chiropody, developing and reducing—also hundreds of reliable formulas for beauty preparations, including cold creams, skin bleaches, liquid and dry powders, rouges, depilatories for removing superfluous hair, shampoo mixture, hair tonics and restorers, curling fluids, bust developing, reducing, remedies for wrinkles, pimples, blackheads, freckles, liver spots, sunburn, eyes, mouth, hands, feet, exercises, diet and miscellaneous valuable hints—as taught at Paulette School. Washington, DC: Author.

Johnston, J. F. (1886). The chemistry of common life (8th ed., Vol II). New York: D. Appleton and company.

Parascandola, J. (2012). King of poisons: A history of arsenic. Dulles, VA: Potomac Books Inc.

Poucher, W. A. (1932). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (4th ed., Vol. 2). London: Chapman & Hall Ltd.

1887 Dr. Campbell’s Arsenic Complexion Wafers. This was the main brand of arsenic complexion wafer sold in the United States.

1890 Ammett’s French Arsenic Complexion Wafers.

1897 Union Manufacturing and Agency Company Arsene Pilules (arsenic pills).

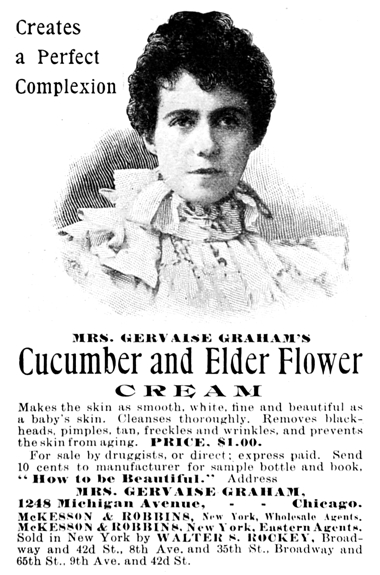

1899 Mrs. Gervaise Graham’s Cucumber and Elder Flower Cream.

1890 Beetham’s Cucumber and Glycerine Cream.

1908 Beetham’s Lait Larola.

1921 Adèle Millar’s Cucumber Vanishing Cream.

1956 Helena Rubinstein [1872-1965] juicing cucumbers in the lab for a publicity shot.